新加坡CUBES专访:Creating Sponge Cities

近日新加坡知名杂志CUBES,对北京大学教授、土人设计创始人俞孔坚进行了专题采访,采访过程中俞孔坚结合实践案例介绍了他的海绵城市理念,并针对新加坡未来城市的规划建设提出了一些建议,他提出,如果能把生态智慧整合到工程系统中,新加坡将会变成海绵国家,从而达到可持续发展的目标,解决洪水问题。

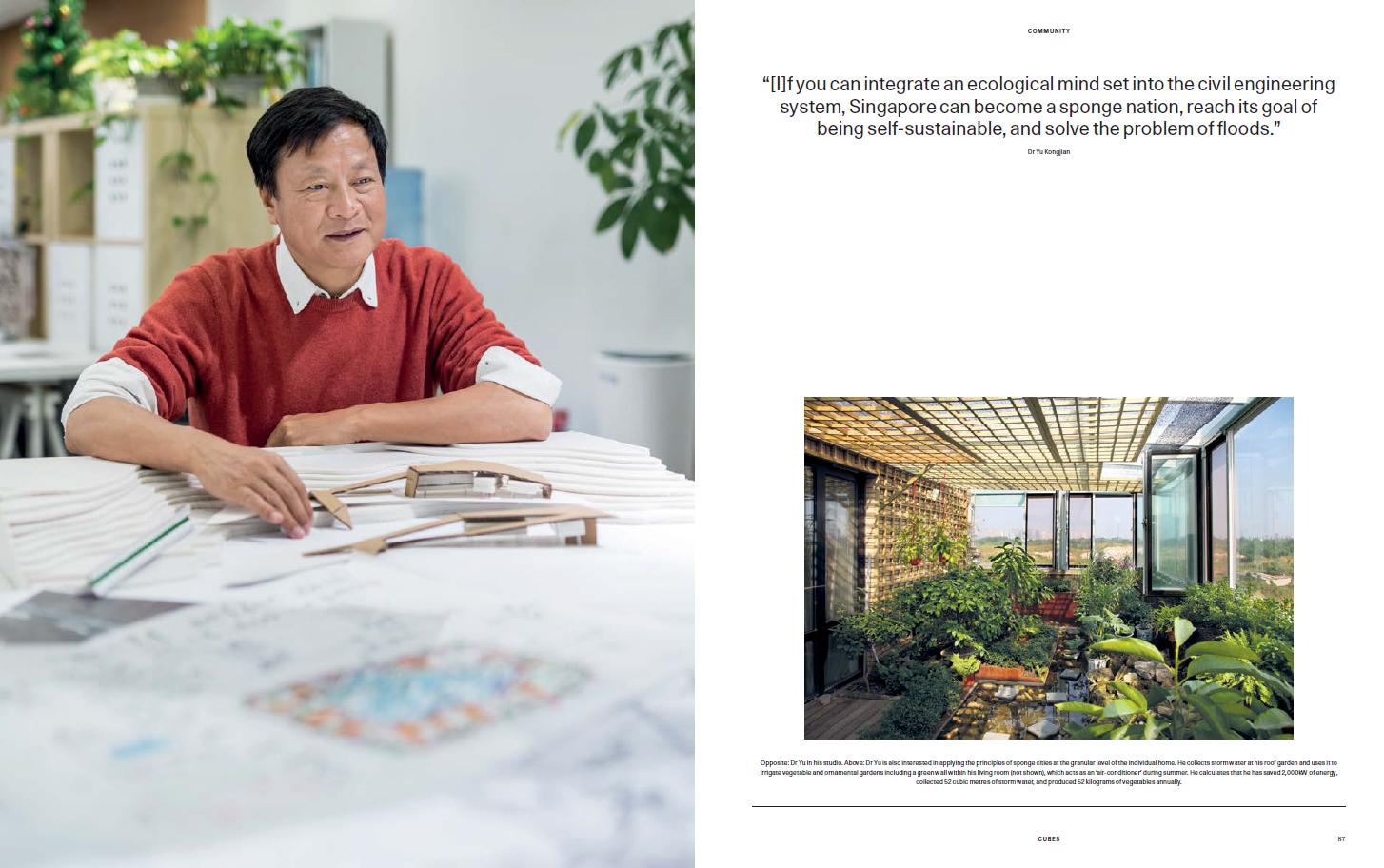

Dr Yu Kongjian, the founder of Beijing-headquartered

multi-disciplinary design and engineering firm Turenscape, is a

leader in the development of landscapes that combat flooding

while repairing ecological damage and winning hearts.

Opposite: Dr Yu Kongjian founded Turenscape in 1998. The firm is one of the first and largest private architecture, landscape

architecture and urbanism practices in China. He is pictured in his work zone at Turenscape’s Beijing headquarters.

In Asia’s rush towards urbanisation, a post-industrial framework of water management has largely been adopted. It is characterised by draining water away from our cities as quickly as possible, using pipes and concrete drains. Tropical Asian cities, however, unlike their European counterparts, are prone to sudden monsoonal downpours, leading to issues of flooding in cityscapes that are ill equipped to deal with torrents of water.

Dr Yu Kongjian, founder and Principal Designer of Turenscape and Dean of the College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at Peking University, presents the idea of Sponge Cities – a concept synthesising modern water management systems with the ancient Chinese agricultural wisdom deployed in rice paddies and ponds. Sponge Cities retain and slow down the flow of water through the use of terraces, ponds and dykes. Urban landscapes become active systems that absorb excess water during monsoon rains, retain and filter it within a meandering landscape, and release it for use during dry seasons. The Sponge City solution to urban inundation has been applied in over two hundred cities in China and beyond, gaining credence as the Chinese government’s adopted urban ecology framework.

Water-scarce Singapore certainly has reason to take a leaf or two out of Turenscape’s book. China holds twenty per cent of the world’s population, and yet only has access to eight per cent of global freshwater. Retaining water is thus a key national policy issue – a familiar refrain in Singapore. When asked for his thoughts on Singapore’s ecological development, Dr Yu raises several pertinent points. “Singapore has built so much, all its rivers are channelised. Ramboll Atelier Dreiseitl did a great job with Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, but you have 100 more canals to deal with,” he jests. “There is strong bureaucracy and an established infrastructural framework – but if you can integrate an ecological mind set into the civil engineering system, Singapore can become a sponge nation, reach its goal of being self-sustainable, and solve the problem of floods,” he adds.

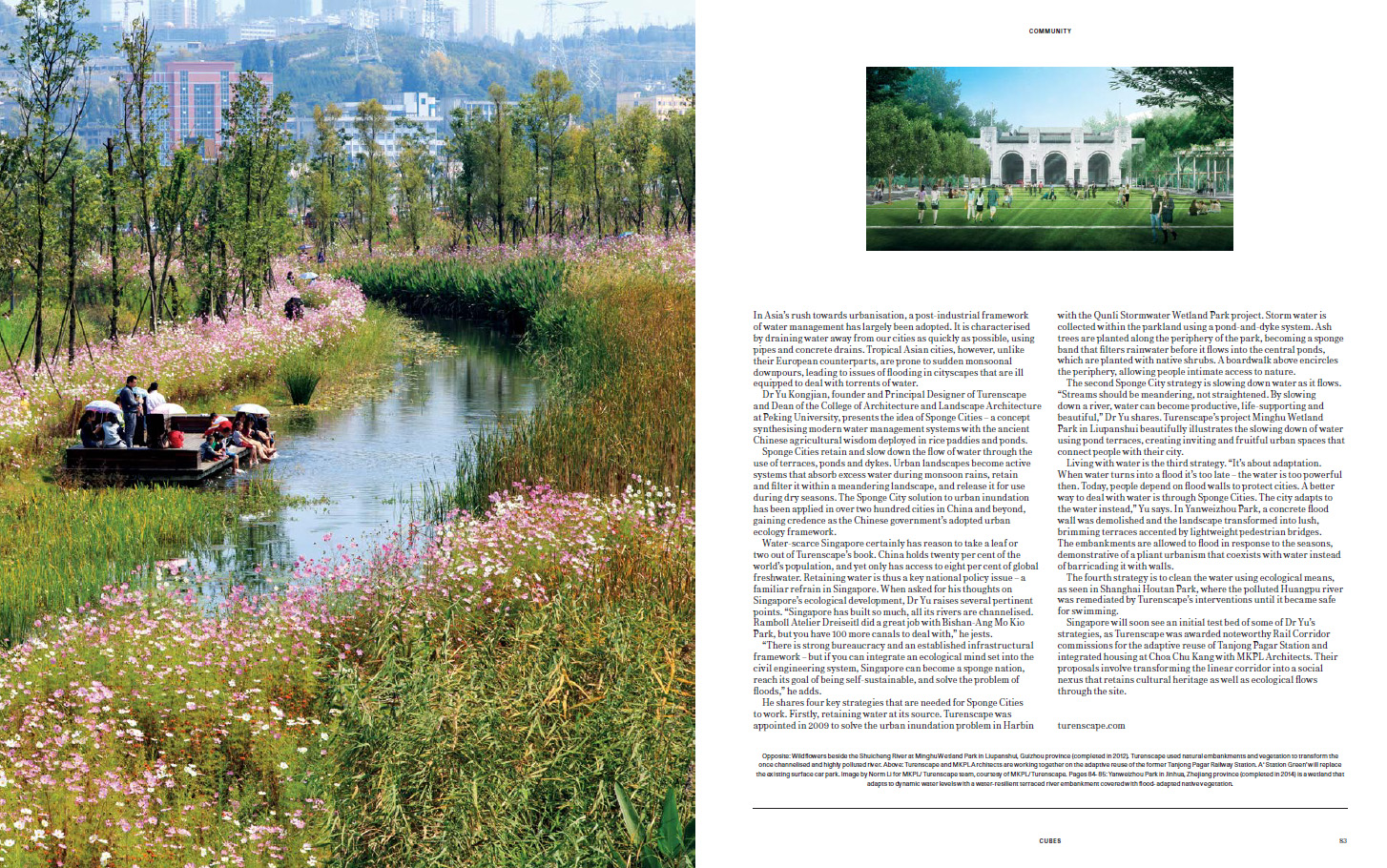

He shares four key strategies that are needed for Sponge Cities to work. Firstly, retaining water at its source. Turenscape was appointed in 2009 to solve the urban inundation problem in Harbin with the Qunli Stormwater Wetland Park project. Storm water is collected within the parkland using a pond-and-dyke system. Ash trees are planted along the periphery of the park, becoming a sponge band that filters rainwater before it flows into the central ponds, which are planted with native shrubs. A boardwalk above encircles the periphery, allowing people intimate access to nature. The second Sponge City strategy is slowing down water as it flows. “Streams should be meandering, not straightened. By slowing down a river, water can become productive, life-supporting and beautiful,” Dr Yu shares. Turenscape’s project Minghu Wetland Park in Liupanshui beautifully illustrates the slowing down of water using pond terraces, creating inviting and fruitful urban spaces that connect people with their city.

Living with water is the third strategy. “It’s about adaptation. When water turns into a flood it’s too late – the water is too powerful then. Today, people depend on flood walls to protect cities. A better way to deal with water is through Sponge Cities. The city adapts to the water instead,” Yu says. In Yanweizhou Park, a concrete flood wall was demolished and the landscape transformed into lush, brimming terraces accented by lightweight pedestrian bridges. The embankments are allowed to flood in response to the seasons, demonstrative of a pliant urbanism that coexists with water instead of barricading it with walls.

The fourth strategy is to clean the water using ecological means, as seen in Shanghai Houtan Park, where the polluted Huangpu river was remediated by Turenscape’s interventions until it became safe for swimming.

Singapore will soon see an initial test bed of some of Dr Yu’s strategies, as Turenscape was awarded noteworthy Rail Corridor commissions for the adaptive reuse of Tanjong Pagar Station and integrated housing at Choa Chu Kang with MKPL Architects. Their proposals involve transforming the linear corridor into a social nexus that retains cultural heritage as well as ecological flows through the site.

Opposite: Wildflowers beside the Shuicheng River at Minghu Wetland Park in Liupanshui, Guizhou province (completed in 2012). Turenscape used natural embankments and vegetation to transform the once channelised and highly polluted river. Above: Turenscape and MKPL Architects are working together on the adaptive reuse of the former Tanjong Pagar Railway Station. A ‘Station Green’ will replace the existing surface car park. Image by Norm Li for MKPL/Turenscape team, courtesy of MKPL/Turenscape. Pages 84-85: Yanweizhou Park in Jinhua, Zhejiang province (completed in 2014) is a wetland that adapts to dynamic water levels with a water-resilient terraced river embankment covered with flood-adapted native vegetation.

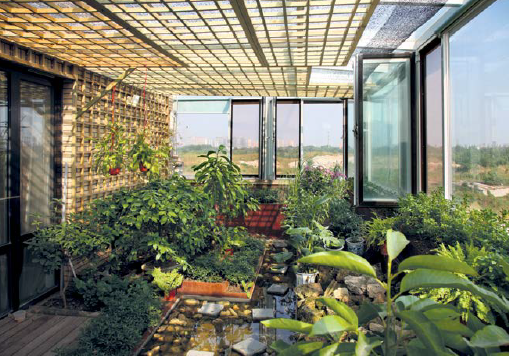

Opposite: Dr. Yu in his studio. Above: Dr. Yu is also interested in applying the principles of sponge cities at the granular level of the individual home. He collects storm water at his roof garden and uses it to irrigate vegetable and ornamental gardens including a green wall within his living room (not shown), which acts as an ‘air-conditioner’ during summer. He calculates that he has saved 2,000kW of energy, collected 52 cubic metres of storm water, and produced 52 kilograms of vegetables annually.