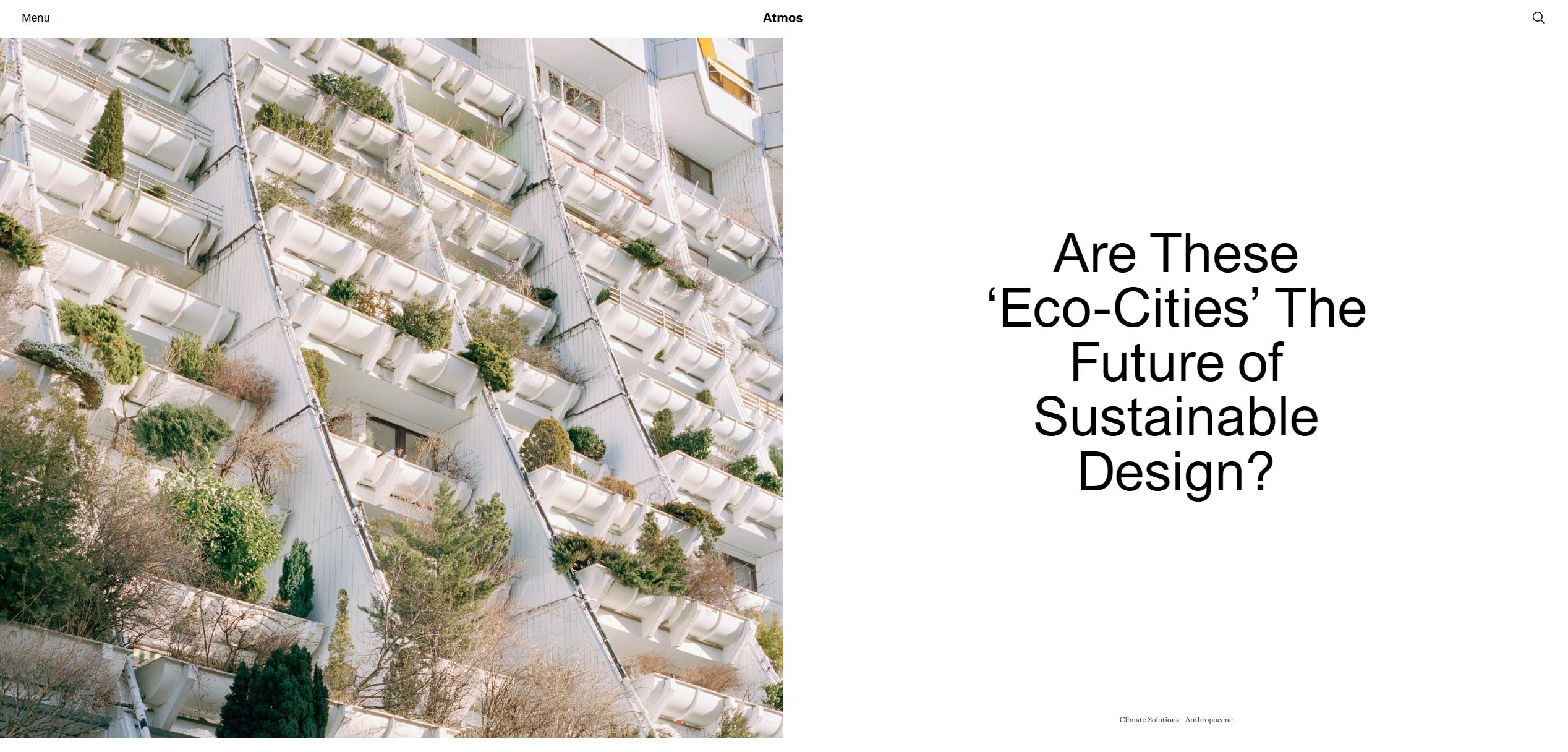

Atmos:“生态城市”是可持续设计的未来吗?

These urban design solutions might save us (and our cities) from climate change, but only if they can overcome the numerous obstacles that stand in the way.

Cities are like gigantic babies, according to architect Daniel Sundlin. Our most essential needs–food, water, energy, and infrastructure material–seldom come from the cities we reside in. Rather, they’re reliant on places and people hundreds of miles away. “In terms of how we build them, they’re just dependent on a lot of other systems and people around the world to survive,” Sundlin said.

In recent years, so many cities have only narrowly escaped dramatic confrontations with climate change, their fragile systems and infrastructure nearly steering them to the edge of collapse. This is why architects and designers are no longer just envisioning adaptive, self-sufficient, and sustainable utopias—they’re building them.

Today, cities are being constructed with some of the most ambitious design solutions in mind, shifting our idea of what a utopia could and should look like. After all, what’s the perfect place if it can’t withstand the wrath of a planet scorned?

With over 50% of the world’s population living in urban cities, a number that’s predicted to grow to 70% by 2050, many of us might be experiencing these innovations sooner than we think. Will you be flying in an electric “air taxi” in the Arabian desert? Or 3D ocean farming in the Yellow Sea? Or maybe you’re staying put, installing permeable pavement in your driveway in case your street floods.

Certain elements of these designs that have been around for years are now being shaped to serve a fast-evolving world where urban enclaves and nature are increasingly forced to coexist. Perhaps these future metropolises will be our saving graces. Or maybe they’ll crumble under the pressure.

The “Sponge City”

The sponge city design is arguably one of the more practical and proven urban design solutions.

Coined by Chinese architect Yu Kongjian, the term “sponge city” refers to a nature-based design method that counteracts flooding by embedding more absorbent materials within a city’s infrastructure. Most urban cities are considered concrete jungles—but, the sponge city design replaces the all-too-familiar hard, gray framework with what’s called “green and blue infrastructure” such as parks, gardens, lakes, and wetlands.

This infrastructure allows rainwater to be absorbed back into the Earth, or to be captured and reused for plant irrigation or in household cooling systems. Traditional architecture on the other hand, forces that same water to be redirected to drains and then out to sea as stormwater, which can get backed up and lead to floods.

This spongey practice will inevitably become a big part of future sustainable design, especially as extreme weather, storms, and flooding continue to threaten cities, predicts water expert Dr. Erik Porse. “When you design, you look to historical hydrology, historical storms,” Dr. Porse told Atmos. “With climate change, that storm design is changing.” As weather patterns evolve, so too will the metrics for successful urban design.

Retrofitting this kind of layout into a city’s existing infrastructure, however, can be difficult, particularly in Western cities. “If working in a city in the U.S. or Europe that’s been there for thousands of years, pipes and drainage are already built, and the design is more compact, so expensiveness and space are challenges,” Dr. Porse said. Generally, it’s much easier to achieve sponge-like structures when building a city from scratch, like in China, where 30 sponge cities have already been constructed. Because when starting from scratch, new infiltration bonds between streets can be built in order to route the water appropriately.

If architects are able to retrofit successfully, the benefits of this design can range from ecological to social to economic.

Still, if architects are able to retrofit successfully, the benefits of this design can range from ecological to social to economic. Whereas impervious concrete surfaces result in rainwater ripping through soil, gathering dirt and garbage with the runoff, and ultimately ruining the natural ecology, a softer design would reduce both localized flooding, and the amount of contaminants getting sent to watershed, benefitting fish, wildlife, and plants. Plus, a study by design firm Arup found that nature-based infrastructure is 50% more affordable than human-made alternatives, and 28% more effective.

Scalability is both a solution—and another challenge. On one hand, sponge features are often implemented on relatively small scales and are therefore less effective than if they were to cover the area of a large city. But, smaller sponge city projects also allow communities to take the reins and have more autonomy when preparing for the effects of climate change in their neighborhoods.

This was the case for a community in New Orleans when Groundwork New Orleans helped residents install a 600-foot bioswale to soak up water in a local flood zone. “Now it doesn’t flood anymore and that road is clear for people to evacuate the city,” said executive director Todd Reynolds.

New Orleans has the most impervious concrete per capita compared to other cities in the U.S., said Reynolds, meaning it’s not just the huge hurricanes that are the issue—day-to-day life can be hampered by a simple thunderstorm. Therefore every tree, raingarden, and greenroof the organization installs is a success. “We’re leaving a resilience asset in communities,” Reynolds said.

This absorbent method of construction has proven to work—at least on smaller scales around the world. But let’s face it: major cities are sinking, and a sponge can only soak up so much water. What if it’s time to abandon land completely, and set our sights (and our sails) out to sea?

A visualization of the floating city prototype “OCEANIX Busan”, courtesy of OCEANIX/ BIG- Bjarke Ingels Group

With global sea level rise steadily ticking upwards, architects and designers are starting to take the concept of the floating city much more seriously than in years past.

Granted, people have been living on and near water for generations, but recent designs have reimagined water-based living with climate resiliency as the end goal. Off the coast of Busan, South Korea, for instance, a 4.5 acre, multi-platform floating prototype plans to accommodate a “resilient and sustainable floating community” of 12,000 people. “What we’re doing is adding a layer of sustainability and scalability,” said Daniel Sundlin, one of the lead architects for the project, named OCEANIX Busan.

So, how does a marine city of this size not simply float away? Well, the idea isn’t to be drifting in the middle of the ocean; rather, it would be chained down to the bottom of a harbor not far from land with flexible anchors made from biorock. Those chains will then relax over time in order to rise along with the sea.

Many floating city projects have been proposed over the years, but OCEANIX Busan seems to be the closest to coming to fruition, a testament to the practicality of its design, said Sundlin, who specializes in floating structures. “It’s always been a utopian idea, but our [design] is practical,” he said.

The hexagonal shape of the platforms allows for buoyancy, and would also be able to support the weight distribution of multi-level buildings without being impacted by incoming waves. This makes the living experience potentially more stable than buildings on land, since land is also constantly moving due to “wind and movements below,” said Sundlin.

Historically, a city has been limited by the capabilities of the surrounding land to support it, ultimately defining its scale—like with the sponge city design. But as the population grows and space on land lessens, life on water could eliminate that issue. For OCEANIX, this would look like a closed loop system around food, water, and energy. Urban farming on and around the platforms, waste used as plant fertilizer, 100% renewable energy using solar, wind, and water, and desalination of seawater are all part of the design solutions to make this the ideal eco-city.

Historically, a city has been limited by the capabilities of the surrounding land to support it…but as the population grows and space on land lessens, life on water could eliminate that issue.

But as with any utopian idea, skepticism around feasibility and cost trail closely behind.

A prominent criticism of floating cities is that most of the materials necessary to meet its needs have embedded carbon activity in their production. Sundlin admits that there are major carbon processes associated with floating cities, particularly the transportation of materials, construction of infrastructure, and demolition or reuse of a product, which all contribute to emissions.

“That can be addressed in different ways,” said Sundlin. “[Using] a combination of metal and wood that’s sourced locally or recycled is a great way to reduce [emissions] in the construction phase; we’re always going to have some kind of footprint, but it can be addressed in the operations of building.”

For many architectural processes this is where a “life cycle analysis” of a project comes in. At the beginning of a project, carbon emissions can be high; in fact, they most likely will be. But, using carbon sequestering techniques such as generating and creating biomass by planting material for ocean life or replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy all help to reduce that carbon footprint until it becomes neutral. Ideally, at the end of a building’s life cycle, its emissions would be carbon negative.

Floating cities certainly fall on the ambitious side of sustainable design solutions, but not outside the realm of reality. Still, if the idea of living in open water just doesn’t appeal to you, there’s a far drier potential eco-city out there. In the desert valley of Saudi Arabia exists an even more ambitious design vision. One, that’s been met with more skepticism than hope—but one that could become the vanguard of sustainable solutions if successfully accomplished.

“The Line” in NEOM

The Line is an architect’s dream. It’ll be the flagship city of NEOM, a mega-city development spanning the coast, desert, and mountains of Saudi Arabia that’ll use smart technology and other innovations to attempt to address nearly every climate threat. The city will be divided into five “regions,” among them a floating city prototype named Oxagon and an island resort called Sindalah.

But the NEOM team plans for The Line, scheduled to be completed by 2030, to be the epicenter for activities and the primary home for residents. In this sense, NEOM executive director Giles Pendleton claimed, The Line is NEOM.

It would accommodate nine million people within 34 square kilometers, completely immersed in nature. But the part that has piqued the interest of visionaries, designers, and architects around the world is its plan to fit a city comparable to the size of Manhattan into the space of a 500-meter tall, 200-meter wide, completely vertical mirrored structure, stretching over 100 miles across the desert. It’d resemble a skyscraper, except instead of extending up toward the clouds, it’d reach toward the hazy ends of the desert. Hence, the name “the line.”

Several architecture studios are in the midst of bringing this vision to life, taking turns to build the first five of what will become 140 modules, each one 800 meters long and designed to house 80,000 people. Residents are required to have access to whatever they need within a five-minute walk through surrounding greenery, and would be able to travel end-to-end within 20 minutes using an underground high-speed rail network. The idea is for there to be zero cars and for the entire city to run on 100%renewable energy from solar, wind, and hydrocarbons—a vision that is being described as an “environmental solution to urbanism.”

It’d resemble a skyscraper, except instead of extending up toward the clouds, it’d reach toward the hazy ends of the desert.

A major urban center powered exclusively by clean energy is a tough task for any country to achieve; but the fact that this promise comes from the largest oil exporter in the world has caused a large amount of skepticism around the future city’s sustainability goals.

“The project’s ambition to be a fully sustainable city from an energy perspective appears overly optimistic and potentially unsustainable,” said global energy expert Justin Dargin. “This clean energy transition, especially on the scale proposed for The Line, is unprecedented and will likely encounter numerous unforeseen technical and logistical hurdles.”

Granted, the vision does align with Saudi Arabia’s broader goals of achieving net zero emissions by 2060; but, this is also the same country that was the largest obstacle in a global deal to phase out fossil fuels at last year’s COP conference. Even so, the visionary behind the project, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, has maintained faith that the country will achieve its goals and The Line will thrive as an example.

The Line’s assembly, however, has drawn deeply concerning red flags. Its construction has reportedly resulted in the forced displacement of the indigenous Huwaitat tribe, and three members have allegedly been sentenced to death for resisting eviction from their ancestral homeland, according to ALQST, an independent group monitoring human rights in Saudi Arabia. A man was also shot and killed by Saudi security forces in 2020 for reportedly protesting the forced displacement of himself and other members of the Huwaitat tribe.

Outside of the serious human rights violations that have prompted the UN to urge foreign investors to ensure they are “not causing or contributing to” state violence, NEOM’s location in a prominent petro-state also raises concerns for a couple of its grand ambitions. These include becoming the world’s most food self-sufficient city and becoming completely self-sufficient in its water production. Seeing how Saudi Arabia currently imports 80% of its food, this shift would require an adoption of “cutting edge agricultural techniques such as hydroponics, aeroponics, and vertical farming,” said Dargin, all of which would involve growing crops in a way that minimizes water consumption.

Architects are designing the future, and with it comes both awe-inspiring possibilities and disappointing realities entwined with its materialization.

As for maintaining a sustainable water supply without the use of fossil fuels—well, it’s never been done before. “The current state of desalination technology is heavily dependent on energy-intensive methods, primarily fueled by carbon-emitting hydrocarbons,” said Dargin. Therefore advanced desalination technologies and water recycling and conservation systems would be crucial. After all, in order to maintain The Line’s attractive claim to rest at an “ideal climatic temperature” year round, the city needs a solid water system, along with help of energy efficient HVAC systems, artificial intelligence, and of course the extensive urban green spaces like parks and green roofs.

As is the case for floating cities, sponge cities, and our standard urban city, achieving net zero will be a journey, primarily because of how dependent our global systems and infrastructure are on fossil fuels.

Architects are designing the future, and with it comes both awe-inspiring possibilities and disappointing realities entwined with its materialization—a reminder that a design solution to climate change will never be simple. The criticisms of these future eco-cities are valid—carbon-intensive processes, long-term sustainability, and not to mention, potential resources that could be better used toward updating our current cities. Furthermore, any eco-city that promises utopian living cannot also perpetuate existing oppressive systems and state violence against marginalized communities.

Utopian ideas are embedded into the design world—even more so now that many urban centers are under constant attack from climate disasters. Whether we’re drawn to the idea of a new city or would rather dream up ways to rebuild our present dwellings, our biggest impact will ultimately come from finding natural ways to decarbonize our cities, said Porse. “No matter if they’re in the water, land, or air.”

Source:https://atmos.earth/are-these-eco-cities-the-future-of-sustainable-design/