Domus:海绵城市:土人设计的亲水愿景

A hydrophilic vision

A hydrophilic visionLast October, I spenta week in Xixinan, a charmingfarrm-oriented village three hours by train west ofShanghai,and now increasingly a destination forurban visitors. The Fengle River fows by the villageand a dam to the north modulates the flow ofwater, creating twochannels.

One is the modulated river itself and the otherisa canal that quietly weaves through the village, structuringits spatial order and irrigating thegardens. China's acclaimed landscape architedt andecological planner Kongian Yu has set up a base inthe village upgrading many of the old houses fornew uses and establishing a research laboratory forPeking University and his practice Turenscape." Despite the metropolitan scope of his projectsand inceasing international engagements, Yu'sthinking and practice remain bound to a vllage-river fabric.

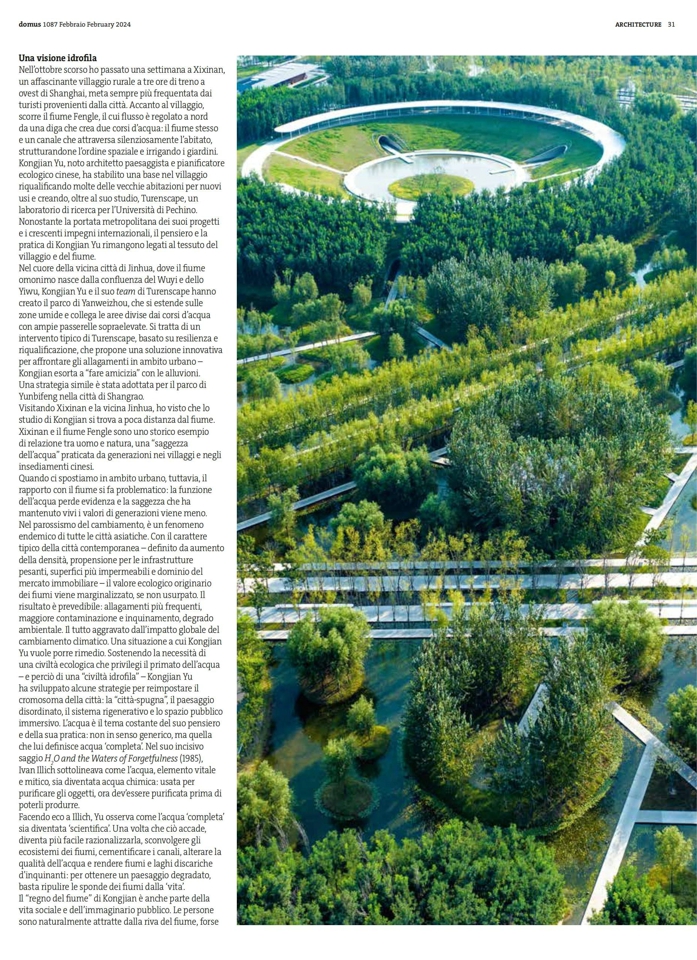

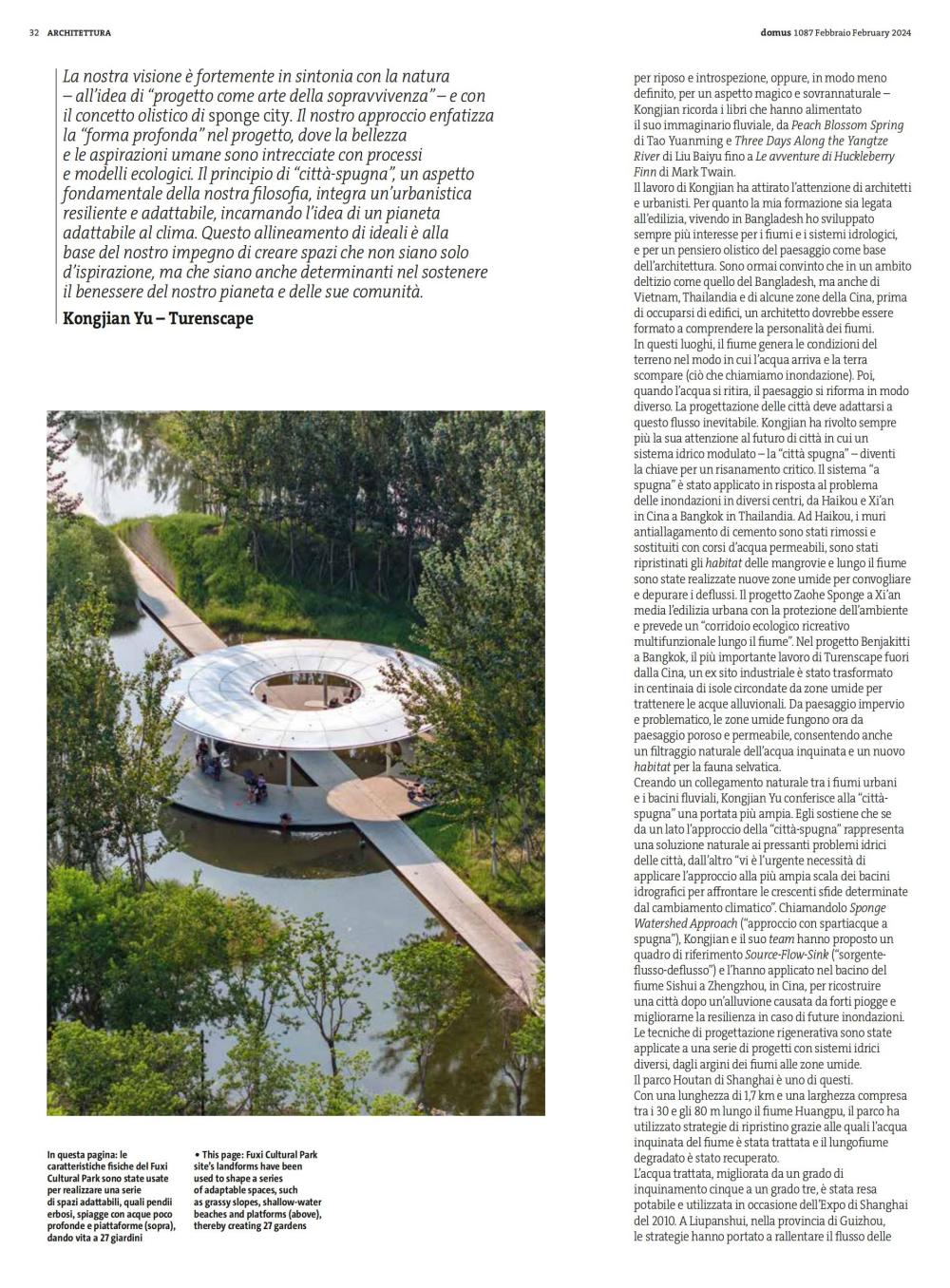

In the heart of the nearby city of Jinhua where theWuyi and Yiwu rivers converge to form the linhuaRiver, Yu and his team at Turenscape created theYamweizhou Park that spreads across the wetlandsand connects areas divided by the rivers withsweeping elevated walkways.

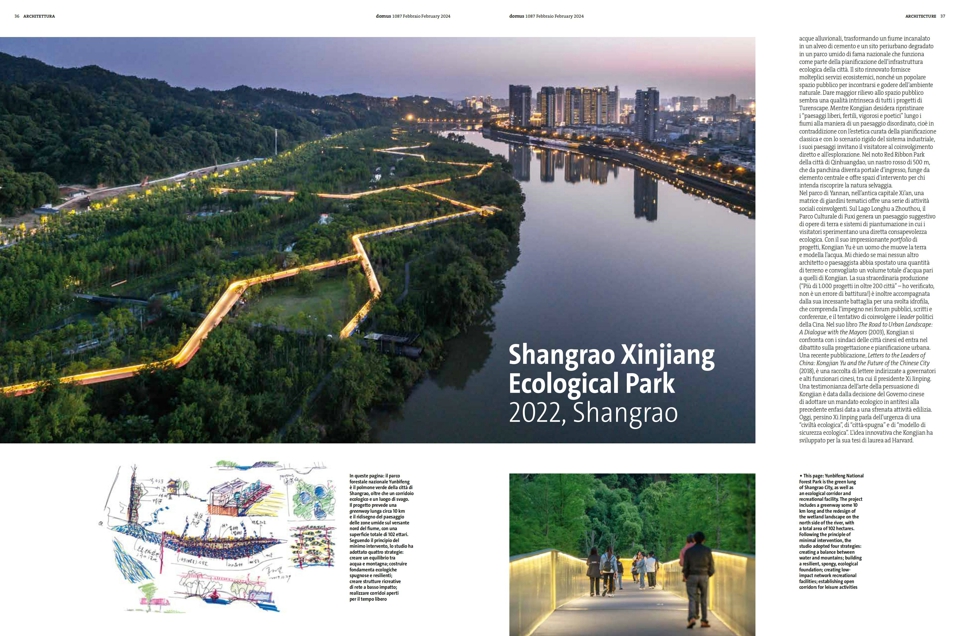

It's a classie Turenscape work representing aresilient and restorative design, in which a newmeasure is offered for dealing with urban floods. "Make friends" with fooding. as Yu implores. A similar strategy was taken up for the YunbifengPark in the city of Shangrao.

Visiting Xixinan and nearby linhua, Irealised thatwhere Yu is, the riveris not faraway. The village of Xixinan and the Fengle River form the most ancientreciprocity between humans and nature,a wisdom of water practiced through generations in China's villages and settlements.

Yet, there is trouble in the city when it comesto rivers-the property of waterfalters and thewisdom that maintained generational valuessuccumbs. This is endemic to all Asian citiesin the paroxysm of change. With the genericcharacter of the contemporary city -increasingdensity. propensity for hard infrastructure, moreimpermeable surfaces and realestate domination-the original ecolopical value of rivers is marginalised, if not usurped.

The result is predictable: more urban flooding.greater contamination and pollution, and envirommental degradation. All of which is nowaggravated by the globalimpacts of changingclimate. Yu wants to rectify that.

It is not any water; it is what he calls "complete" water In his powerful essay H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness (1985), Ivan Ilich remarked how H2O-the water that was used to purify things nowneeds to be purified before you can do things.

Echoing Illich, Yu observes how “complete” water has become "scientific" water

And once that happens, it becomes easier to streamline water, disrupt stream ecosystems, concretise channels, alter water quality, and makerivers and lakes dumping fields for pollutants. It is enough to clear the riverbanks of “life”, and eventually arrive at a sordid landscape.

Yu's "river realm" is also part of a social ife and thepublic imaginary.

People are naturally drawn to the edge of the river, for recreation and introspection, perhaps, and not quite mapped out, for something magical and phenomenal. Yu recalls the books that have fed his river imaginary, from Peach Blossom Spring by Tao Yuanming and Three Days Along the Yangtze River by Liu Baiyu to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain.

Architects and urban designers have been drawn to Yu’s work. I am trained in making buildings, but, living in Bangladesh, I have increasingly developed an interest in rivers and hydrological systems, and a holistic landscape thinking as the basis of architecture. I am now convinced that in a deltaic place like Bangladesh, and for that matter Vietnam, Thailand and parts of China, an architect should first be trained in understanding the personality of rivers, before handling buildings. In such terrains, the river is the basis of “ground” conditions, in how the water arrives and the land vanishes (or what we call flooding), and when the water recedes, the landscape is recreated in a different way.

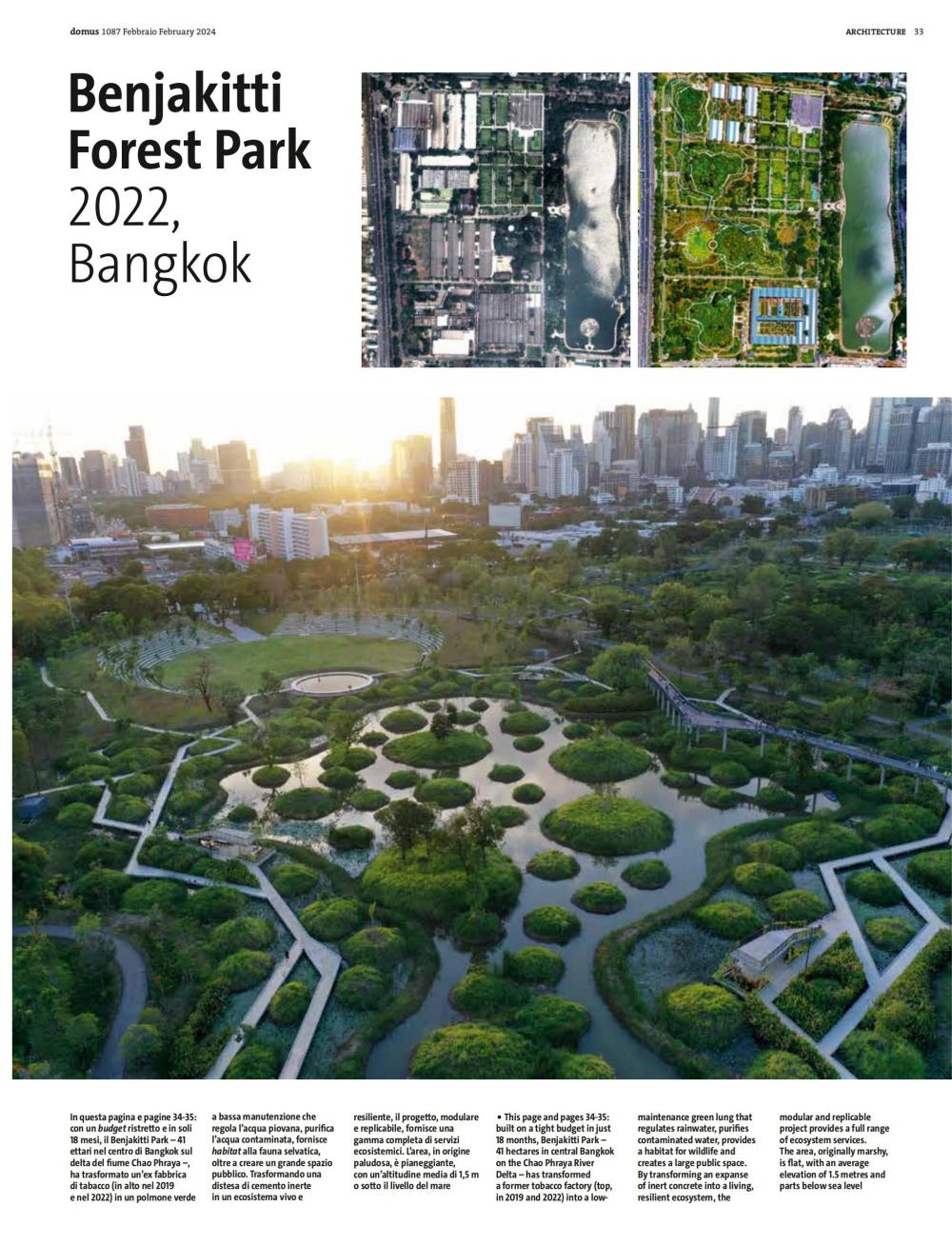

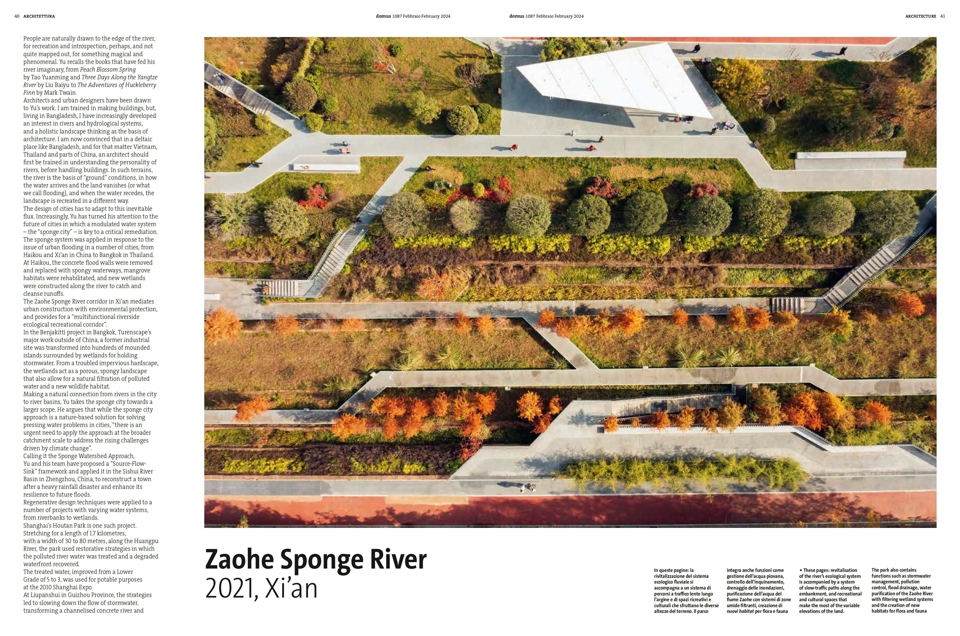

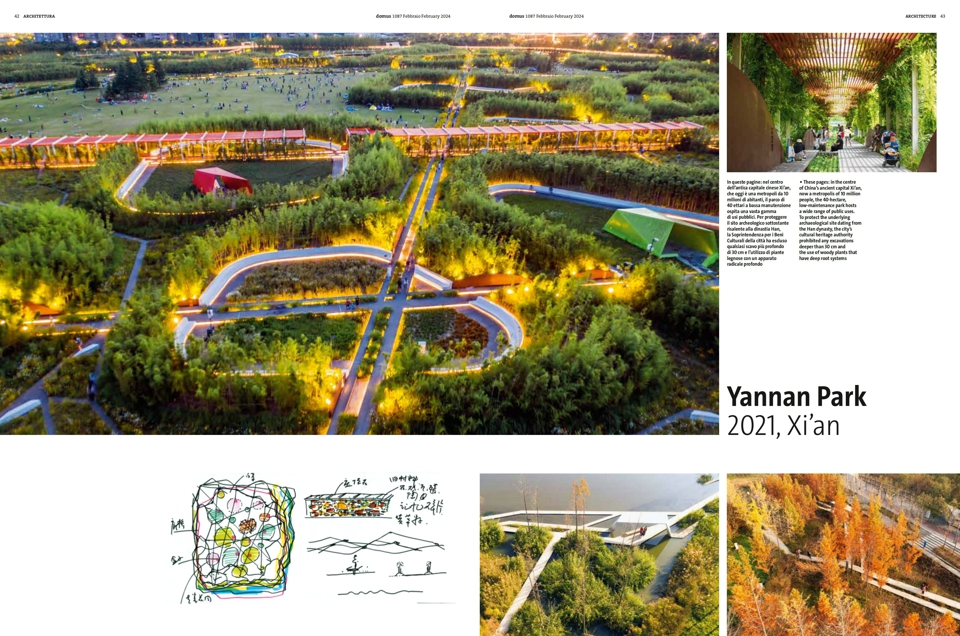

The design of cities has to adapt to this inevitable flux. Increasingly, Yu has turned his attention to the future of cities in which a modulated water system - the “sponge city” – is key to a critical remediation. The sponge system was applied in response to the issue of urban flooding in a number of cities, from Haikou and Xi’an in China to Bangkok in Thailand. At Haikou, the concrete flood walls were removed and replaced with spongy waterways, mangrove habitats were rehabilitated, and new wetlands were constructed along the river to catch and cleanse runoffs.

The Zaohe Sponge River corridor in Xi’an mediates urban construction with environmental protection, and provides for a “multifunctional riverside ecological recreational corridor”.

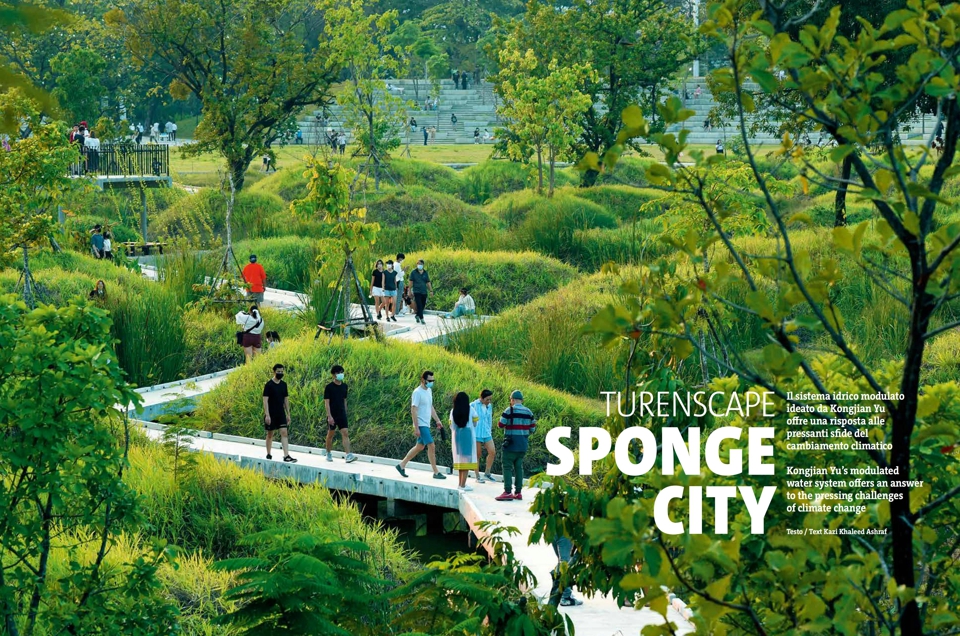

In the Benjakitti project in Bangkok, Turenscape’s major work outside of China, a former industrial site was transformed into hundreds of mounded islands surrounded by wetlands for holding stormwater. From a troubled impervious hardscape, the wetlands act as a porous, spongy landscape that also allow for a natural filtration of polluted water and a new wildlife habitat.

Making a natural connection from rivers in the city to river basins, Yu takes the sponge city towards a larger scope. He argues that while the sponge city approach is a nature-based solution for solving pressing water problems in cities, “there is an urgent need to apply the approach at the broader catchment scale to address the rising challenges driven by climate change”.

Calling it the Sponge Watershed Approach, Yu and his team have proposed a “Source-FlowSink” framework and applied it in the Sishui River Basin in Zhengzhou, China, to reconstruct a town after a heavy rainfall disaster and enhance its resilience to future floods.

Shanghai’s Houtan Park is one such project. Stretching for a length of 1.7 kilometres, with a width of 30 to 80 metres, along the Huangpu River, the park used restorative strategies in which the polluted river water was treated and a degraded waterfront recovered.

At Liupanshui in Guizhou Province, the strategies led to slowing down the flow of stormwater, transforming a channelised concrete river and a deteriorated peri-urban site into a nationally celebrated wetland park that functions as part of the city-wide ecological infrastructure planning.

The refurbished site provides multiple ecosystem services, as well as a popular public space for gathering and enjoying the environment.

An intensification of the public realm seems to be an intrinsic quality of all Turenscape projects. While Yu wishes to restore the “free, fertile, vigorous and poetic landscapes” along rivers in the manner of a messy landscape, that is, in contradistinction to the manicured aesthetic of classical planning, as well as the hard landscape of the industrial regime, his landscapes invite public engagement and exploration.

In the well-known Red Ribbon Park in Qinhuangdao, a 500-metre red ribbon, alternating from a bench to gateways, acts as a central element woven through the park that offers interventional spaces for people to rediscover the wilderness.

Yu’s breathtaking portfolio of projects makes him a mover and shaper, a mover of earth and a shaper of water. I wonder if any other architect or landscape architect has reshaped the volume of earth and redirected the total volume of water that Yu has. His unbelievably prodigious output (“over 1,000 projects across 200 cities” – I had to do a double take on this statement to make sure I wasn’t misreading it!) is also matched by his relentless campaign for a hydrophilic turn that includes an engagement at public fora, writing and speaking, and reaching out to the leaders of China.

His book The Road to Urban Landscape: A Dialogue with the Mayors engages with the mayors of Chinese cities and enters into the discourse of urban design and planning. An updated publication, Letters to the Leaders of China: Kongjian Yu and the Future of the Chinese City, is a collection of letters addressed to Chinese governors and high-ranking officials, including President Xi Jinping.