徽州传统水文化景观的结构特征与当代价值

- 摘要:

- 水文化是水生态文明建设的重要方面,而传统水文化景观作为水文化的重要载体,其研究和保护具有重要的现实意义。本文提出水文化景观概念,即人类通过水事活动对其所处环境进行改造而产生的景观,是人类对水利用、改造和管理的综合结果。徽州传统水文化景观持续了上千年,作为一个系统概念,集中展现了徽人的生态智慧:以塘、堨、水口为代表的各构成要素相互依存,形成了聚落、农田、河流等景观组分,并适应了盆地、溪谷、山丘等地貌条件,构建了城镇、村落及生产的水安全格局。徽州传统水文化景观依赖于长期的维护和管理,是徽人的生活基础和徽文化的表征。徽州传统水文化景观是当代水利建设和管理的重要补充,是海绵国土的重要生态基础设施,也是遗产保护和旅游融合发展的重要资源。 Water culture is one of the key issues in Water Ecological Civilization. China’s traditional water cultural landscape embodies rich water cultures, and have a significance in related research and protection practice. This paper proposes the concept of “water cultural landscape,” that is, the landscape formed through humans’ environmental alteration during water activities—including how people use, transform, and manage it. The traditional water cultural landscapes in Huizhou Region have developed over hundreds of years, reflecting the locals’ wisdom in sustainable water use. The water cultural landscape in Huizhou Region should be interpreted as a systematic notion, in which all landscape elements such as ponds, weirs, and shuikous are interdependent, composing the landscape components e.g. valleys, hills, and basins, and establishing water security patterns for cities, towns, villages, and for production. The traditional water cultural landscape in Huizhou Region requires local generations’ long-term maintenance and management, and in turn it is also vital to Huizhou people's life and Huizhou culture. Today, it acts as an ecological infrastructure for sponge countryside and sponge city construction, and an important resource for heritage protection and tourism development.

文章来源:史书菡, & 俞孔坚. (2021). 徽州传统水文化景观的结构特征与当代价值. 景观设计学(中英文) 9(04), pp.28-49.

1.引言

水生态文明是当下生态文明建设的重点工作,而水文化是水生态文 明建设的重要部分[1][2],传统水文化的传承及传统水利工程等文化载体 的保护则是其中重要的评价指标[3]~[5]。中国传统农耕智慧,尤其是在 水的管理和利用方面的智慧,对当今国土修复和城乡治理具有重要的 借鉴意义[6][7]。基于传统水管理智慧的文化景观不仅是水文化的载体, 也是重要的地域性文化遗产和旅游资源[8][9]。水文化景观是自然系统、 文化系统和社会系统的有机结合,基于多学科视角进行研究是必要且必须的。

徽州是中国区域史研究中的典型区域之一,更是研究水文化景观 的理想区域。对历史上(特别是明清时期)徽州整体历史文化的研究, 一定程度上是对整个中国传统社会后期经济文化的典型个例分析[10]。由 于徽州拥有较为完整的历史资料记载和传承,历代均有较为稳定的社会 经济条件,使得这些文化能够长久延续—徽州形成的水文化景观持续 发展了上千年之久,至今仍留存着传统水利设施和水管理方法。以聚落 水景观为主的徽州水文化景观研究多聚焦于水口的设计及营建理念[11], 对徽州历史上灌溉管理也有一定的梳理和考证[12][13]。研究多立足于历史 学、社会学及建筑学视角,尚未有基于景观生态学视角完整梳理徽州水 文化景观系统的研究。

基于此,本文正式提出“水文化景观”的概念,根据历史文献资料 和场地调查,以景观生态学视角完整梳理徽州水文化景观系统,探究徽 州水文化景观的构成和特征,剖析传统经验和管理智慧,为当代水文化 保护和资源开发的研究与实践探索思路。

2 水文化景观的概念

目前,水文化景观相关研究涉及城市滨水景观[14]~[16]、旅游开发[17] 及遗产保护[18]等方面,与“水文化景观”直接相关的概念包括“水文 化”和“文化景观”等。

“水文化”的概念源于20世纪80年代末的水利研究领域[19]。随后诸 多学者针对水文化做出了不同定义。其中,汪德华认为水文化是“人类社会历史发展过程中积累起来的关于如何认识水、治理水、利用水、爱 护水、欣赏水的物质和精神财富的总和”[20]。2008年出版的《中华水文 化概论》提到:“水文化是人们在水事活动中,以水为载体创造的各种 文化现象的总和,或是说民族文化中以水为轴心的文化集合体”[21]。学 界已从文化传承与发展的角度提出“水文化遗产”的概念,即在历史时 期内,人类对水的利用和认知过程中所留下的文化遗存[22]。而“水利遗 产”则包含在“水文化遗产”之内,更侧重于水利的工程性遗存[22]。水 文化包含意识形态(精神)、行为规范(制度)、物质形态(物质)三 个层次[19],能够完整囊括“水文化遗产”和“水利遗产”的内容。

“文化景观”的概念源于地理学领域,由19世纪德国地理学家奥 托·施吕特尔首次提出[23][24]。20世纪20年代,美国地理学家卡尔·O· 索尔创立了伯克利学派[25],认为文化景观是在任何特定时间内,自然和人 文因素复合作用于某地形成的,会随人类的行为活动而不断变化[26][27]。随 着文化景观概念的不断发展,可将其视为以自然景观为本底,经过人类 活动而改造的景观,具有适应性、层级性和关联性等属性[28]。文化景观 强调人与环境之间存在的精神联系,反映出人与环境的互动[29]。

由此,本文提出,水文化和文化景观在概念上的交集即为“水文化 景观”,并将其定义为:人类通过水事活动对其所处环境进行改造而产 生的景观。由于景观是人与人、人与自然关系在大地上的烙印,是人类 文化和理想的载体,而景观本身即为一种生态系统[30],这两个因素共同 决定了水文化景观具有社会和生态的双重属性。水文化景观是人类对水 利用、改造和管理的综合结果,往往能够反映水可持续利用的方法和技术,在当代水保护与水利用方面具有借鉴意义。

水文化景观与水文化遗产在概念上具有交集,具有遗产价值的水文 化景观属于水文化遗产的物质层面,而水文化遗产的非物质层面不仅影 响水文化景观的形态特征,更决定了其能否持续发展。虽然水事活动、 水管理技术等水文化遗产的非物质内容不属于水文化景观的范围,但可 以反映在水文化景观的演变过程和形态之中(图1)。

3 徽州传统水文化景观

根据前文针对水文化景观的定义,徽州传统水文化景观①则指历代 徽人通过一系列水事活动对徽州地区改造而产生的景观,包括徽州聚落 的生活用水系统、农田灌溉的生产用水系统、防水御灾的水利系统,以 及与水相关的各类空间、建筑、设施等。

从整个中国农业灌溉水利史来看,徽州几乎涵盖了水利设施的所有 类型,是一个典型的水利区[31]。从聚落营建的角度来看,徽州水系营建 的类型复杂多样;从整个区域文化发展的角度来看,徽州水文化景观集 中体现了徽人的生产生活智慧。徽州地貌丰富,决定了徽州水文化景观 的多样性。在景观尺度上,包括溪谷、山丘、盆地等类型;分析到景观 组分,可分为聚落、农田、河流等水文化景观;再聚焦到景观要素,则 由塘、堨、水圳、堤坝、水口等构成(图2)。

《徽城竹枝词》以诗词的形式歌咏了清代歙县的风土民情,从不同 角度展现了徽州水文化景观的地域特色。其中“祠堂社屋旧人家,竹树 亭台水口遮”描绘了聚落中的徽州水文化景观;“灌田所重在开塘,东 路名塘多别乡”描绘的是农田生产灌溉用水系统;“渔梁坝璧石层层, 潴蓄奔流关替兴”表现的是水利系统与徽州风水文化的融合;而“府城 多井少池塘,夏月荷花不见香”更是勾勒出了明清徽州城镇空间中的水文化景观。

3.1 徽州传统水文化景观的构成要素

徽州传统水文化景观各要素之间相互作用,并在历代徽人的管理和 协调之下,构建了徽州水文化景观的安全格局。首先,除了日常生产所需用水之外,徽州农业高度依赖灌溉设施,塘、堨的修建是重中之重。 其次,徽州水灾比旱灾的危害更大,严重威胁当地居民的生产生活[32], 需要修建堤坝、水射等水利设施。另外,徽人的风水思想根深蒂固, 历代徽州商人和乡绅常会为祈求一都一邑一村之平安,斥巨资建设水口。由此,本文将徽州水文化景观构成要素分为“保障生活”“控水御 灾”“聚落营造”三类。

3.1.1 保障生活

3.1.1.1 潴水以备需

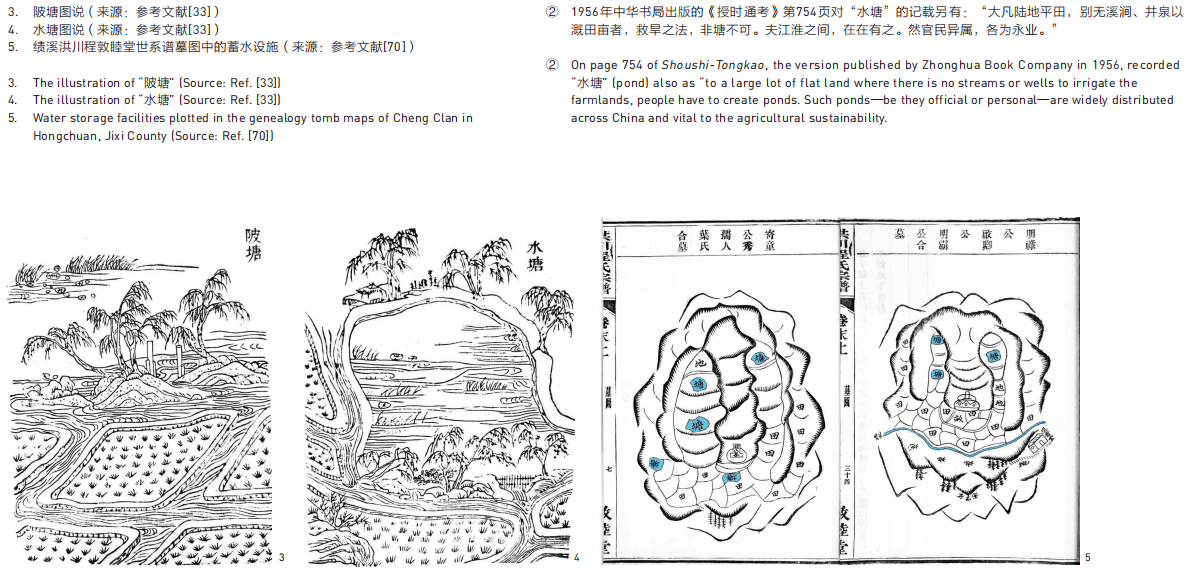

清代《授时通考》中对陂塘的解释为:“陂,野池也,塘,犹堰 也。陂必有塘,故曰陂塘。漑田大则数千顷,小则数百顷”(图3)。 而其中对水塘的解释为:“水塘,即洿池,因地形坳下,用之潴蓄水 潦,或修筑圳堰,以备灌漑田亩”[33](图4)。可见陂塘和水塘具有相 似性:陂塘面积较大,多位于山地,利用自然地形形成的“野池”进行 人工筑堤,可灌溉几百甚至上千顷的田地;水塘则更多处于洼地之中, 多为平坦地形条件下的“灌田之法”,大多数是官民产业②。此外,还 包括“水堀”:“堀”意为“穴”[34],“水堀”则是一种储水设施,本 质上是一种小型的塘[35]。上述蓄水设施可统称为“塘”。徽州当地根据 塘所处位置不同,有不同的称谓:在山谷中堆土筑坝以蓄水灌溉的称为 “山塘”,即“陂塘”;在田畈中挖土成坑蓄水、提水灌溉的称“平 塘”[36]。除了农业灌溉之外,塘等蓄水设施还可满足日常浣洗、防火御 患和渔业养殖生产活动等需求。

徽州地区地形复杂,陂、塘、堀等的建造与地形、田地分布息息相 关。在徽州明清方志中,只有婺源、祁门和休宁有“陂”的记录[37][38], 而其他各县则多有“塘”的记录③,这与婺源、祁门等地多丘陵的地貌 有关。无论是鱼鳞图册中的田土图,还是家谱中的墓图,均表现出当时 蓄水设施随地形和居民的需求变化而变化的特点(图5),体现了徽人 适应自然的智慧。

“潴水以备需”的各类水塘是历代徽人重要的经济资产④,并依赖 徽人长期的维护和管理延用至今。当今徽州的聚落水塘各具特色,是徽 州重要的景观资源(图6,7)。田地中的塘多用于农田灌溉,不仅可以 在冬春季节蓄水,在稻作生产期间也可以调节灌溉水量(图8)。但由 于当代农业从业者数量的减少及农业生产对水塘依赖性的降低,徽州部 分塘业已荒废。

3.1.1.2 导水资功用

徽州地区河网密集,近河区域的导水利用比潴水更加高效。庞大的 用水系统囊括了多种引水设施,其持续运行依赖于有效的协调和管理, 高度集中了徽人因地制宜的智慧。

(1)堨

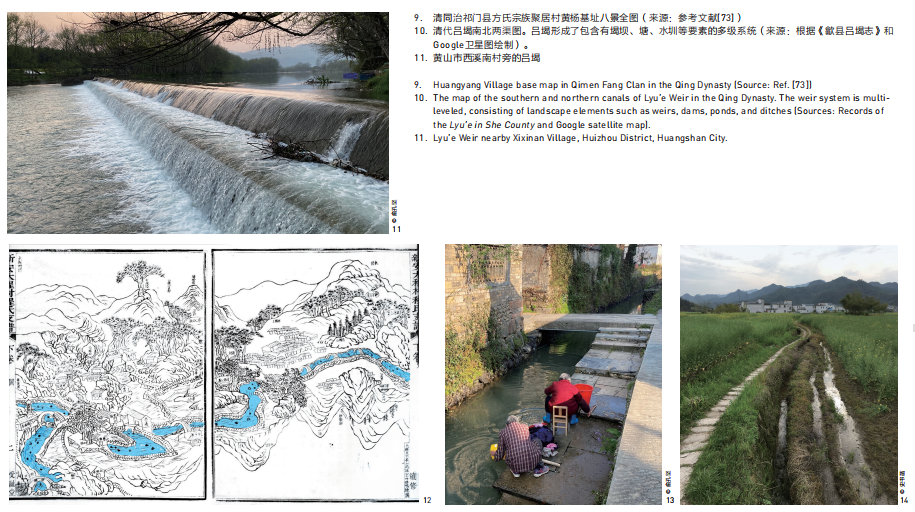

堨在徽州地区历史悠久,最早可追溯至魏晋时期。“堨”(徽州 也称“碣”),指“遏水的土堰”[34],是徽语特征词[39],在徽州历代方 志、村志及历史文献中,“堨”屡见不鲜。清同治《祁门县志》中详细 记载了平坦近河地区灌溉造堨的原因,即“按田在山谷者为山田,在旷 野者为坂田。坂田远山谷,不资塘水资溪水,乃为堨。”[40]清道光《休 宁县志》[41]及清代同治祁门方氏宗谱的黄杨村基址图(图9)中均有与 堨相关的记载。徽州的“堨”指在河流上修建坝、堰等设施,抬高水 位,引水入渠,进而灌溉农田或营建村落水系的整套引水系统。其水源 来自河流,而坝、堰等设施是此系统获得水源的关键—保证堨内田地 获得相应的灌溉用水(图10)。

当今,堨在徽州地区仍发挥着重要作用。在丰乐河畔的西溪南村的 雷堨、条堨、陇堨等引水系统确立了村落水系统的主体架构,保障着村 民的日常生活水源(图11)。然而,西溪南村原吕堨灌区内的大部分土 地已转变为建设用地,多数硬化的堨渠也已不再发挥灌溉功能。丰乐河 上游修建的堤坝、水库等现代基础设施,与这些传统堨渠共同维持着丰 乐河流域的水源供应,并提升了该区域的旱涝适应性。

(2)水圳

水圳⑤是具有特定功能的人工水渠系统,可分为农业灌溉和生活保 障两类(图12)[42]。田间水圳多作为塘或堨系统的一部分,沿着田塝、 田塍修建以便引水灌溉,尤其是为水稻种植提供必要的水源。村落水圳 多沿村中主街分布,串联村落中的鱼塘、堨坝、水口,并与村外河流相 连。现今,水圳仍是徽州人工水系统的重要元素;许多村落水圳高低错 落,保持着旧时特色,在保障村落排水排污的同时,服务着居民的日常 生活(图13,14)。

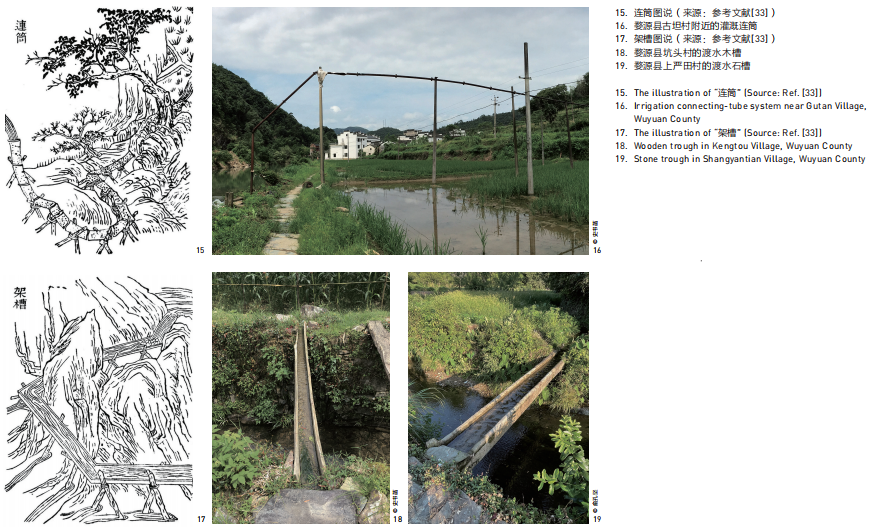

(3)连筒

在《新安竹枝词》中写到“接竹引泉勤灌园,半邻城市半山 村”[43],其中“接竹引泉”指的正是当地的一种灌溉手段[43],《授时通 考》记载的“连筒”,指的也是这种在徽州地区沿用至今的灌溉方式 (图15)[33]:“连筒,竹通水也。凡所居相离甚远,不便汲用,乃取大 竹,内通其节,令本末相续,连延不断。”[33]。当今,徽人将传统经验 与现代材料相结合,运用连筒原理,简易搭建:村民将水管连接并架高,抽取河上堨坝积蓄的水源,引水灌溉附近高地的农田(图16)。

(4)架槽

《授时通考》中记载:“架槽,木架水槽也。间有聚落去水既远, 各家共力,架木为槽,递相嵌接,不限高下,引水而至”(图17)[33]。 现今,徽州地区仍保留着各类小型木质或石质架槽(图18,19),可灵 活引水;另有长距离的混凝土架槽,能够保证引水效率。

3.1.1.3 筑井供灌饮

在20世纪90年代以前,徽州地区乃至中国许多地区主要通过修筑 水井来获取饮用水源。徽州地区水井一般深3~5m,最深不过7m。部分 山区地下水位很浅,可设置自流井或水池,供灌溉或饮用[44]。当地村民 会定期对水井进行维护,如绩溪县上庄村于每年农历六月六日清理水井 (俗称“换井”)—修葺内、外井边,清除井里的渍泥—并在井内 放养鲫鱼来判断水质的安全[45]。

徽州现今仍保存着的多处古井是重要的水文化景观。但由于自来水 的普及,多数井水已不再作为饮用水使用,而成为了村民日常盥洗的辅助水源(图20,21)。有些村落将水井改建为压水井,另有部分水井与 抽水设施结合使用,在旱时用以灌溉。

3.1.2 控水御灾

3.1.2.1 堤

民国《歙县志》简明地阐释了“堤”与“坝”的区别:“凡迭石累 土截流以缓之者,曰坝。障流而止之者,曰堤”[46]。坝是横向截流河水 以使河水流速放缓的设施,在徽州多称为“堨”;而“堤”(也称“堤 坝”)则多设置于河道两侧,保护田舍免受洪水侵扰[46]。虽然徽州的堤 坝较少,但《歙县志》中的水利部分先介绍“堤坝”,塘堨置于其后, 并提及“由于徽州地区山洪的破坏性巨大,如此安排是为了显示堤坝的 重要性”[46]。

3.1.2.2 水射

《歙县志》中记载,“御其冲而分杀之曰射”[46],其中“御其冲” 指抵御水流冲击和侵蚀;“分杀之”指改变水流方向。“水射者,方言 即防壍也”[46],在汊道河流的干支流汇合处,由于河道侵蚀、泥沙堆积 成沙洲,在此处建设水射,以解决河床分汊的问题[46]。水射的原理则类 似于现代水利工程建设中广泛应用的丁坝,体现了徽人对水力学原理的 思考与应用。清代学者凌应秋曾为歙县昉溪居民解决洪涝困扰,著文提 及“疏浚水滩,以分杀水怒”,并“障倾泻”,修建目的和方式均与水 射类似[47]。现今的徽州仍保留着水射固堤护宅的做法(图22)。

3.1.2.3 水碓

直至20世纪60年代,水碓一直是徽州各地常见的舂米榨油工具[48] (图23)。《授时通考》中称,“凡流水岸傍,俱可设置”[33],徽人因 地制宜,拦河筑堨获取水头,引水冲碓。水碓在徽人的日常生活中占有重要位置,清代汪由敦的诗句“石堨横截水溅溅,水碓风轮疾转圜”[49] 就描绘了水畔田园劳作的美好图景。

水碓在服务徽人日常生产的同时,也引发了多种利益冲突。水碓建 设需要筑坝拦水,然而此举会影响河道的正常运转,常引发河道拥塞、 航运受阻等问题。徽州文书中曾记载,在清康熙年间祁门金竹洲下游水 碓的兴建影响了上游水碓,造成了“废坏上碓”的后果[50]。又如歙县吕 堨的用水条例中规定,堨内水碓根据灌溉时段即时封闭,以解决居民在 水碓使用和堨水灌溉上的冲突,同时勒碑规定了使用水碓的禁忌[51]。现 今,随着碾米机等现代机器设备的引入,水碓原本的功能逐渐被取代, 而水碓的参与体验性使其成为了体验式旅游、亲子研学旅游发展的重要文化资源(图24)。

3.1.3 聚落营造

3.1.3.1 水口

水口作为水的出入口,是聚落景观的关键节点。徽人重视风水,为 防止“走泻”,需在水流出之地建设构筑物,“聚一乡之树木、桥梁、 茶亭、旅社,以卫庇一乡之风气也”[52]。因此,水口不只是水设施,也 是徽州聚落风水营造的关键,更是景观系统的重要组成部分。水口的类 型变化多样,包括水口桥、水口亭、水口庙、堨坝、水碓等,并兼具生 产、生活和生态功能。其级别由水口所在河流干支流的位置所决定:位 于新安江上游的渔梁坝为徽州府总水口,而位于岩寺镇丰乐河上的水口神皋塔则为一邑之水口。最为常见的一乡或一村之水口,多位于村落水 系统的出口处(图25)。而在一村之中,又有一重水口和二重水口,大 水口和小水口,内水口和外水口之分。水口的日常修缮费用多依靠村人 捐助,徽州文书和方志中就大量记载了徽人“乐助水口”的事例[53][50]。

遗憾的是,大量的水口在当代遭受了破坏,人们的风水思想也发生 了巨大变化[54]。不过,水口文化在徽州尚有延续,婺源县严田村将水口 保护条例写入了现今的“村规民约”,在一定程度上保护了水口林等生 态资源。徽州多地保存完好的水口景观成为了重要的旅游资源,如黄山 市徽州区西溪南村水口处的木桥、低堰、枫杨林等(图26,27)。

3.1.3.2 天井

天井是徽派建筑的特色元素,也是徽州建筑中与水息息相关的空 间结构。天井除了通风、采光等功能外,还有雨水导引、收集和储存的 区域。徽人认为聚水即为聚财,屋面的雨水也应“四水归名堂”“肥水 不留外人田”。因此,徽派建筑的屋顶设有水枧,使得雨水顺势汇入天 井下的水池(图28),或储存在太平缸(即水缸)之中(图29),多余 的水则由阴井或暗藏的排水路径承接[55][56]。当今,在徽州传统民居建筑 中,天井处仍会放置水缸,用以收集雨水,防火御灾。

3.2 徽州水文化景观的景观组分

3.2.1 聚落水文化景观

徽州聚落是徽州文化的主要载体。徽州聚落一般临近河流,聚落水 文化景观包含了各类水文化景观的构成要素,是整个徽州大地景观上最具文化内涵的景观组分。明清时期,水系管理是徽州聚落建设中的重 要环节。聚落多引河流之水入村,整个水系统一直是流动的—经由 入水口,流过各级水圳,或流入水塘,最终从出水口重新汇入河流。 这些人工水系统与周边的山林、水系,共同构建了聚落水文化景观系统 (图30)。

聚落水文化景观培育了徽人的生活用水习惯与规则制度:许多徽 州聚落将最大的水圳作为村中的主街,并将这里作为居民日常洗衣、 洗菜、交流集聚的场所,而产生的生活污水经由水圳流出,排到村外城 外,以保证村落内部用水安全;明清时期制定的分时段用水措施[11]也一 直延续至今,如黄山市的西溪南村仍保持着清晨不得洗涤的规则制度。 这些传承下来的非物质遗存是水文化景观可持续存在的重要因素。

3.2.2 农田水文化景观

徽州地区人多田少,“徽处万山之中,无水可灌,抑若无田可耕”。徽州地处皖南山区,地势高峻,易涝易旱每遇暴雨,极易发生 洪涝灾害,“郡地势高峻,骤雨则苦潦”[37];短期无降雨,则又农田干 涸,引发人蓄饮水问题,所谓“易日不雨又苦旱”[37],“十日不雨,则仰天长呼”[38]。徽州地区的地质条件对旱涝的适应性很低,依靠水利改 造艰苦的耕作环境是徽人生存与发展的重大课题。

鱼鳞图册反映出徽州农田水文化景观主要由塘、堨、水圳等灌溉设施要素构成,其中鱼鳞总图清晰绘制了各类农田的实际位置(图31), 在不同的地形和水文条件下,塘、堨、水圳等要素数量不一,而田地获 取灌溉水源的难易程度也决定了其土地价值。总体而言,塘、堨是徽州 农田水文化景观中主要的构成要素,构成了历代“塘堨并举”的景观格局,而有效的管理保证了农田水文化景观的可持续性,并形成了徽州鲜明的地域特征。

3.2.3 河流水文化景观

徽州河网密布,各级河流串联了各级城镇、村落。历史上,徽商多 沿新安江顺流而下,前往苏杭谋求生计;徽州向来缺粮,从外地运来的 粮食也须依靠河流的运输。一进一出,都关乎徽人民生。徽人通常在河 上筑坝来抬高水位,并建设码头,以保障航运。其中,历代官员和乡绅 出资修建的渔梁坝不仅是徽州著名的物资中转地,也是徽州的总水口, 而此处逐渐形成的水运和码头文化(图32),丰富了徽州河流水文化景 观的内涵。

3.3 徽州水文化景观的类型

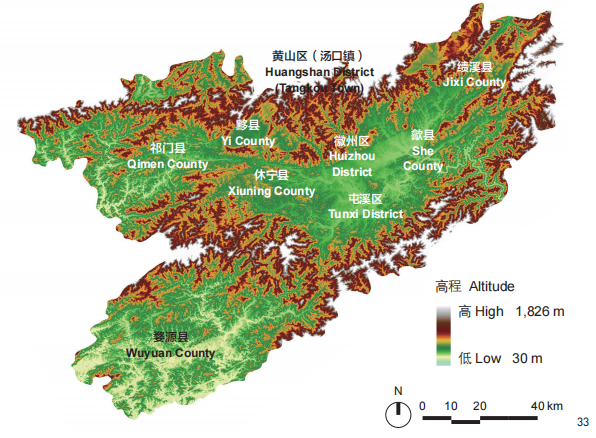

徽人的生产和生活区域集中在溪谷、丘陵及盆地地区(图33),而徽州水文化景观也可大致分为这三类,不同的地理条件使得徽州各地 区水文化景观的类型、组分和要素不尽相同。

3.3.1 溪谷水文化景观:村落水安全格局

对徽州大部分地区而言,溪谷成为了居住和耕作的集中地,比如徽 州的祁门、婺源、绩溪的大部分地区。在狭长的溪谷地区,河流串联起 聚落、农田等景观组分,形成了典型的村落水安全格局(图34)。人们 在河流上修建堨坝来抬高水位,再通过水圳引水,以满足农田灌溉和村 落用水需求。明清时期,徽人主要通过宗族管理来规定堨坝的高度、疏 浚水圳、维护水口景观、保护山林,建设村落水安全格局。新中国成立 初期,山林砍伐造成了严重的水土流失,以致砂石壅塞河道,使得溪谷 地区面临航运运输困难、堨坝失修等问题。随着退耕还林政策的实施, 水土流失问题逐渐得到缓解,溪谷地区保留完好的传统村落成为了重要的文化遗产(图35)。建立起适宜的水安全格局,以保障居民生活和农 田用水需求并应对洪涝灾害威胁,是当今徽州地区面临的重要课题。

3.3.2 山丘水文化景观:生产水安全格局

低山和丘陵地区在徽州地形中所占比例较大,也是徽州用于农业 生产的典型区域。在这一区域,聚落选址和农田开垦等土地利用方式可 谓见缝插针。村落建在较为平坦的区域,多临近河流,便于取用生活用 水。山丘上的田地地势较高且远离河流,故水源多依赖山泉或降雨,使 得陂塘蓄水灌溉的作用愈发突出:在高处开垦用水量较少的旱田或林地 的同时,在山坳建设陂塘,收集山上的雨水,而后层级叠落,沟渠相 连,灌溉低地的水田(图36)。

不同于溪谷地区的狭长,山丘区域的面积更广阔,可涵盖一都或一乡 的范围。例如,山丘地貌的休宁县渭桥乡(图37)拥有水田约1 100hm2 , 旱地约35hm2 ,另有油料作物、茶园、果园和桑园,并拥有经果林、油 茶林、烟叶、水面养殖、有机茶、苗木等六大特色生产基地⑥。这些农 业作物的生产高度依赖于水管理和水利用水平(图38)。

徽州的山丘地区,尤其是山坡地,是仅次于盆地的理想耕作场所。 山坡地虽地形有所起伏,但两山间距较宽,可利用的土地较多。徽人利 用地形汇水成塘,依地势进行灌溉,形成了田地灌塘层级分布的格局特 征(图39)。以绩溪县伏岭镇为例,人们在靠近河流的平坦区域种植水 稻,将上方的山坡平整为农田,建造数量众多的陂塘以满足灌溉需求, 还有沟渠串联其间,以此来有效管理水田的用水进出。地势较高的区域 种植的是无需灌溉的竹林,即是当地人的食物来源也是经济来源;地势 最高处为山林,部分裸露的地表生长着徽州特色食材—蕨菜。在这 里,水田、水旱混合田地、竹林、山林的层级结构清晰,形成了山坡地 农业生产的水安全格局。

在清代中后期,徽州山丘地区水土流失情况极为严重,棚民对山地 植被的破坏以及大面积茶树、玉米的种植[57]~[59],使得原本脆弱的土层 在暴雨来袭时不堪一击。新中国成立初期,山丘地区的植被遭到了较大 程度的破坏,以至于20世纪六七十年代常发生地质灾害。80年代后,退 耕还林以及水土保持等举措依次实施,山丘地区的植被覆盖率得到了很 大提高。其中的典型代表即为绩溪县伏岭镇,随着生态逐步修复,旅游 业也逐渐发展,并入选了安徽省首批特色旅游名镇(图40)。

3.3.3 盆地水文化景观:城镇水安全格局

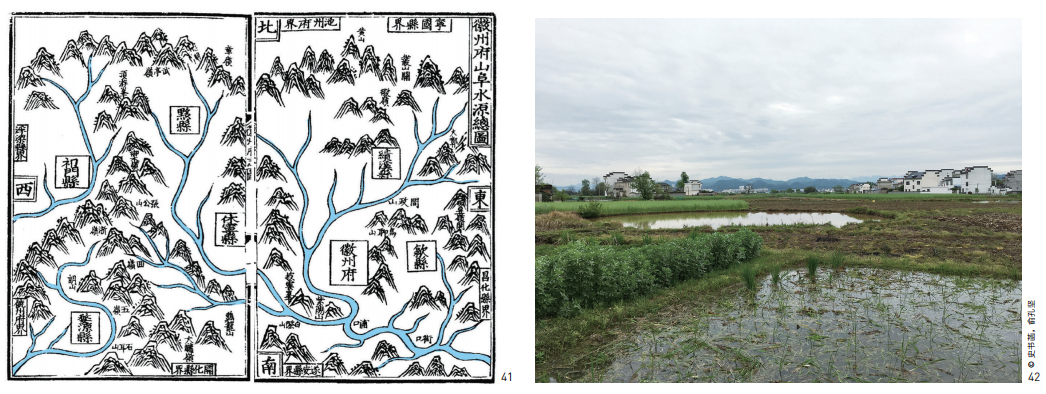

盆地是徽州地区最适宜进行粮食生产、建设城市、以及发展经济的 区域,聚落、农田、河流等景观组分在这里有机结合,孕育了诸多的徽 州名镇、名村。自明清时期以来,徽州的大多市镇就位于较为平坦的盆 地区域(图41),如今的徽州仍然延续着这种传统的城镇建设格局。由 于地势平坦,靠近河流的地区可以引水灌溉,而远离河流的区域则需开 挖水塘,储存雨水,形成了引蓄并重的水系统(图42)。其中,塘系统可削减洪峰,堨系统则可在空间上合理配置水资源,使得这一区域在技 术落后的明清时期亦具有较强的旱涝适应性。

在当今的在城镇化浪潮下,这里的大部分农田早已被一座座现代化 房屋和硬化渠道所取代。耕地的减少、水塘的废弃、硬化地表的增加, 改变了原有的水安全格局,使得近年来城市内涝问题频发。构建城镇区 域的水安全格局,对于解决当代徽州城市水问题具有十分重要的意义。

3.4 塘-堨-水口代表了徽州传统水文化景观的整体特征

塘、堨、水口是徽州水文化景观中最具地域特色的构成要素,承载 着徽州历史发展的印记。塘、堨、水口在徽州聚落、农田、河流等景观 组分中,代表了典型的水文化景观。三者相互协作,共同营建了徽州聚 落水系统(图43)。徽州农田灌溉系统具有“塘堨并举”的景观分布特 征,根据不同类型的农田灌溉需求进行储水或引水操作,或二者结合使 用。徽州河流文化景观系统串联了各级水口和塘、堨:河流的干支流决定了水口的层级,河流的位置决定了塘、堨的分布,并基于此形成了新 安江流域的徽州文化。

在景观尺度上,塘、堨、水口构建了适应于溪谷、山丘和盆地的水 安全格局。在聚落营建的过程中,以水口为核心的水系统规划往往被置 于首要位置。溪谷地区多修堨引水以满足村落用水和农业灌溉;山丘地 区多潴水为塘以保障农业生产;盆地则考虑塘堨并用,通过河流位置决 定塘堨的分布。

因此,塘、堨、水口能够在不同尺度上体现徽州传统水文化景观 的特征:徽州水文化景观是一个系统的概念,以塘、堨、水口为代表的 各要素相互依存;其与人类活动和环境密不可分,依赖长期的维护和管 理;同时也是徽人的生活基础和徽文化的表征。

4 徽州传统水文化景观的当代价值

4.1 农田水利建设和管理的重要补充

在新中国成立初期,人们将遗留的塘和堨加以改造,广泛应用于各 类生产和生活之中,缓解了经济困难时期农业生产中灌溉设施匮乏的状 况。之后,人们开始对历史上塘、堨管理经验展开学习:在黄山市水利 局二十世纪五六十年代的档案资料中,多有对吕堨、鲍南堨等古代管理 经验进行学习和交流的记录,甚至依据《歙县吕堨志》中吕堨条例制定 了放水章程⑦。

长期以来,中国大多数农村地区面临着农田水利设施落后的问 题[60]。自2011年《中共中央国务院关于加快水利改革发展的决定》实施 以来,中央及各级政府加大了农田水利方面的财政投入,资金多用于灌 渠防渗和泵站建设,而对小型塘、渠等农田水系的投入依旧较少[61]。现 存的管理体系难以与基层农民的农业生产进行对接,加之各级管理组织 的统筹问题仍需改善[62]。目前黄山市小型水利设施几乎均为村农民集体 所有,建设投资也基本来自于政府财政补贴⑧,水利部门面临着群众积 极性不高、经费严重短缺等巨大挑战⑨。塘、堨等具有不同景观形态的 水文化景观对应了不同的管理系统,也形成了不同的可持续机制[63]。而 传统水文化景观管理机制中如何提高管理者和基层使用者积极性、如何 针对不同景观形态和功能的水利设施设置不同的管理模式、怎样建立一 套多层级的网络化管理体系等方面的经验,对解决当今水利设施的管理 困境具有重要的借鉴意义。

4.2 海绵国土的重要基础

徽州地区在2020年7月发生了严重的洪水灾害:休屯盆地周边及新 安江上游的雨水汇集,导致局地积水严重,甚至影响了歙县高考的正常 举行。而整个区域范围内小型塘堨的减少,城市不透水面积的增加,以 及水文化景观旱涝调蓄功能的缺失,加剧了洪水灾害的破坏性。这也迫 使我们开始重新思考并系统性地探讨在区域尺度乃至国土尺度上的城市 防洪规划。

“海绵城市”是应对中国季风气候地区旱涝问题的重要理论。我 们需要在多尺度上进行以大地景观为主要载体的海绵基础设施建设, 并将“海绵城市”上升为“海绵国土”战略,而古代传统水文化景观 承载的生态经验和智慧是海绵城市乃至海绵国土建设的重要技术理论 之一[64]。徽人在水资源管理和应对旱涝方面积累了具有生态价值的经验 和智慧[65]:将以小尺度设施为主的徽州传统水文化景观内的各类景观要 素、景观组分有机结合,以适应溪谷、山丘、盆地等不同地理条件,在 雨旱调节等方面发挥“毛细血管”的作用,以此提升水环境的适应能 力,是徽州不同尺度的弹性适应策略和景观遗产[64],是构建海绵田园和 海绵城市的重要基础[66],也是实现乡村振兴的重要生态基础设施[67]。

4.3 遗产保护和文旅融合发展的重要资源

徽州历经千年保存下来的水文化景观是典型的文化遗产,其中水口 景观的旅游开发价值十分明显,而塘、堨等依托于农田灌溉系统也具有 丰富的劳动和自然教育意义,河流线性廊道还可成为水上运动等体育旅 游发展的重要资源。例如,黄山市西溪南村附近的吕堨和水口已成为西 溪南镇的名片,先人的理水智慧在这里得到了传播和发扬,不仅可以发 挥其旅游研学价值,培育旅游新业态,也带动了当地的经济发展和社会 进步[68]。在未来,需深入研究这些文化资源的市场潜力,助力乡村文旅 产业和乡村文化振兴。

5 结语

本文提出水文化景观概念,即人类通过水事活动对其所处环境进行 改造而产生的景观,是人类利用、改造和管理水的综合结果。持续千年 的徽州传统水文化景观凝聚了水可持续利用的地方智慧。徽州传统水文 化景观是一个系统概念,以塘、堨、水口为代表的各要素相互依存,形 成了聚落、农田、河流等不同的景观组分,构建了适应于溪谷、山丘、 盆地等多种地貌条件的水安全格局。徽州传统水文化景观是徽州地区重 要的文化和资源本底[68],也是乡村产业振兴、文化振兴的基础和引擎。 其承载的水管理经验等非物质遗存保障着传统水文化景观的长期可持续 发展,对各类文化遗产的保护和利用具有一定借鉴意义。

Structural Characteristics and Contemporary Value of Traditional Water Cultural Landscapes in Huizhou Region

1 Introduction

Water Ecological Civilization is one of the key issues in current Ecological Civilization, and water culture is an important part of the former[1][2]. The protection of the legacy of traditional water culture and historic water conservancy constructions are critical when considering Water Ecological Civilization[3]~[5]. Chinese traditional agricultural wisdom, especially the wisdom in water management and utilization, can offer reference to today’s territorial restoration and urban–rural governance[6][7]. Cultural landscape shaped by traditional water management wisdom not only embodies rich water cultures, but also becomes important regional cultural heritages and tourism resources[8][9]. Water cultural landscape is an organic combination consisting of natural, cultural, and social systems, which requires multidisciplinary research.

Typically, Huizhou Region, widely studied in Chinese regional history, is an ideal area for studying water cultural landscapes. Such research on the overall historical culture of Huizhou—especially in the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368–1912)—is a typical case of examining the economic culture of the entire Chinese traditional society in the later half[10]. As Huizhou has a relatively completed historical records, and stable socio-economy in history, enabling Huizhou cultures well preserved—the water cultural landscapes in Huizhou Region enjoy a history of thousands of years, and today the traditional water conservancy facilities and water management methods are still in use. Current research on water cultural landscape in Huizhou Region, mainly consisting of settlement water landscapes, focuses on the design and construction of shuikous[11], and overviews of the historical irrigation management in Huizhou Region[12][13]. Such studies are mostly based on the perspectives of history, sociology, and architecture, but existing an absence of review research on the water culture landscape system in Huizhou Region with lenses of Landscape Ecology.

Based on this, this article formally puts forward the concept of “water cultural landscape,” and comprehensively studies the water cultural landscape system in Huizhou Region with the perspective of Landscape Ecology upon historical literature review and site surveys; it also scrutinizes the composition and characteristics of the regional water cultural landscape, and highlights traditional water management wisdom, offering references to the research and practice of contemporary water culture protection and resource utilization.

2 The Concept of Water Cultural Landscape

At present, research interests on water cultural landscape include urban waterfront landscape[14]~[16], tourism development[17], and heritage protection[18]. The concept “water cultural landscape” is closely related with the notion of “water culture” or “cultural landscape.”

Since the term “water culture” has first been used in the field of water conservancy in the late 1980s[19], scholars have developed different definitions, among whom Wang Dehua believes that water culture is the sum of material and spiritual assets about how to understand, mange, use, protect, and appreciate water that would be accumulated during the process of human society[20]. In the Overview of Chinese Water Culture published in 2008, water culture is defined as the sum of various cultural phenomena that emerge during human water activities or represent the cultural aggregation of the nation’s water ideology[21]. The concept “water culture heritage,” put forward from the perspective of cultural heritage protection and development, refers to the cultural relics of using and recognizing water by ancient people[22], which focuses more on the engineering remains such as water conservancy heritages[22]. Water culture can be interpreted in three levels: ideology (spirit), behavioral norms (hierarchy), and material form (material)[19], which covers the implications of both water culture heritage and water conservancy heritage.

The concept of “cultural landscape” was proposed by German geographer Otto Schlüter in the 19th century and first used in the field of geography[23][24]. In the 1920s, American geographer Carl O. Sauer initiated the Cultural Ecology School (Berkeley School)[25], arguing that cultural landscape is formed by the combination of natural and human factors in a certain span of time, and will be constantly reshaped by human activities[26][27]. Through the continuous development of its concept, cultural landscape now can be understood as the nature-based landscape transformed by human activities, which has the attributes of adaptability, hierarchy, and relevance[28]. Cultural landscape emphasizes the spiritual relation between human and the environment, reflecting the human–environment interactions[29].

Therefore, this paper proposes the concept “water cultural landscape” anchored in the intersection of the scope of water culture and cultural landscape, and defines it as the landscape formed through humans’ environmental alteration during water activities. The landscape is the result of interplay between human and nature, which carries human cultures and ideals, as well as the landscape itself being an ecosystem[30]. This defines the duality—social and ecological attributes—of water cultural landscape. This paper argues that water cultural landscape is formed by human use, transformation, and management of water, and often reflects the methods and technologies of sustainable water use, offering reference to contemporary water protection and utilization.

Water cultural landscape with heritage value is part of the physical entities of water culture heritage, while the intangible qualities of water culture heritage not only determine the morphological characteristics of water cultural landscape, but also influence its sustainability. Although the intangible aspects of water culture heritages (e.g. water activities, water management techniques) are not covered in the concept “water cultural landscape,” they are embodied in the process of evolution and formation of water cultural landscape (Fig. 1).

Fig1. Conceptual implications of “water culture,” “cultural landscape,” and “water cultural landscape.”

3 Traditional Water Cultural Landscapes in Huizhou Region

According to the existing definitions of water cultural landscape, in this paper, the traditional water cultural landscape in Huizhou Region① refers to the landscape formed through the local generations’ environmental transformation during water activities, including various water spaces, structures, and facilities related to domestic water system, farmland irrigation water system, and disaster-prevention system in Huizhou Region.

When looking through the history of agricultural irrigation and water conservancy of China, it is safe to say that, as a typical water conservancy area, Huizhou Region has almost all types of water conservancy facilities[31]. Huizhou Region enjoys multiple types of water system construction, and its water cultural landscape also manifests Huizhou people’s great wisdom in production and life. Huizhou Region is rich in landform, which determines the diversity of Huizhou water cultural landscape. In term of landscape scales, it includes valleys, hills, and basins; regarding the analysis of landscape components, it can be divided into settlement, farmland, and river water cultural landscapes; and when focusing on landscape elements, the regional water cultural landscapes are composed of ponds, weirs, ditches, dams, shuikous, etc. (Fig. 2).

Fig2. Types and elements of traditional water cultural landscapes in Huizhou Region

The Huicheng Zhuzhi Poem describes the folks and customs of Shexian County in the Qing Dynasty, outlining the characteristics of water cultural landscapes in Huizhou Region, covering settlement landscapes (“The village has ancestral halls, communal houses, bamboo trees, pavilions, and shuikous”), farmland irrigation water system (“the construction of ponds is critical to the irrigation water system, and famous ponds in the east village are more than other counties”), the integration of water conservancy system and local Feng-Shui culture (“a series of dams built with stones are used to store and regulate water”), and water cultural landscapes in the city (“the town has built more wells than ponds, so the small quantities of lotuses made people less notice them”).

3.1 The Elements of Traditional Water Cultural Landscapes in Huizhou Region

Under the management and coordination of local people over centuries, the security pattern of traditional water cultural landscapes in Huizhou Region has been shaped by the interaction between various elements. First of all, in addition to domestic water use, the construction of water facilities such as ponds and weirs has been critical to the regional agriculture. Second, Huizhou Region has been more vulnerable to floods instead of droughts that has seriously threatened locals’ production and life[32], necessitating the construction of water conservancy facilities such as dams and groins. Furthermore, the locals have profound Feng-Shui ideology. For example, Huizhou merchants and gentries in the past dynasties built shuikous to pray for the safety of their own cities, towns or villages. Thus, this paper categorizes the elements of water cultural landscapes in Huizhou Region by usage types: guaranteeing domestic water use, controlling water and preventing disasters, and building settlements.

3.1.1 Guaranteeing Domestic Water Use

3.1.1.1 Water Storage for Potential Needs

The Shoushi-Tongkao (a classical agricultural book in the Qing Dynasty) interprets “陂塘” (pond) that “陂” refers to the naturally-formed ponds in wild field always followed by “塘” which refers to man-made weirs. Such ponds and weirs are often found in mountainous areas, the water in which can be used to irrigate hundreds-hectares of land (Fig. 3). The book interprets “water storage ponds” as smaller pools that are usually found in low flat lands and used to store water to support irrigation for official or personal farmlands②[33] (Fig. 4). In addition, “水堀” (water cellar)[34], another type of water storage facilities, essentially is a smaller pond[35]. All these ponds are given different names by Huizhou people according to their topographical conditions—for example, the ones created in hills is called “山塘” (hill pond or pond), and the ones dug out in fields is called “平塘” (flat pond) [36]. Beside of agricultural irrigation, ponds and other water storage facilities in Huizhou Region were built to meet people’s daily needs such as washing, fire prevention, and fishery activities.

Fig3. The illustration of “陂塘” (Source: Ref. [33])

Fig4. The illustration of “水塘” (Source: Ref. [33])

The diversely-changing landforms and the distribution of farmlands in Huizhou Region determine the construction of various kinds of ponds. For example, the Ming and Qing chronicles of a few of counties such as Wuyuan, Qimen, and Xiuning had records of “陂”[37][38], while others had more records of “塘”③, which is due to the landform disparity. The local Fish-scale Field Maps and the tomb maps recorded by local genealogies, described the fact that the characteristics of water storage facilities change with the topography and the locals’ needs over time (Fig. 5), reflecting Huizhou people’s adaptation wisdom to the nature.

Fig5. Water storage facilities plotted in the genealogy tomb maps of Cheng Clan in Hongchuan, Jixi County (Source: Ref. [70])

These ponds are Huizhou people’s economic and production assets over the past dynasties④, and carefully preserved and maintained by the locals. Today, the remained ponds in settlements are important regional landscape resources for their vernacular uniqueness (Fig. 6, 7); Ponds in fields are mostly used for farmland irrigation, which can store water in winter and spring, and also adjust the amount of irrigation water during rice cropping (Fig. 8). However, nowadays due to the population decrease of farmers and the less dependence of agricultural production on ponds, some ponds in Huizhou Region have been abandoned.

Fig6. Zhutang pond in Daizhen Park of Huangshan City (built from the late Ming or early Qing Dynasty)

Fig7. Water pond in Yantianwang Village, Wuyuan County.

Fig8. Irrigation ponds in the farmland of Fuling Town, Jixi County.

3.1.1.2 Water Diversion

Due to the richness of Huizhou Region’s river network, water diversion is more efficient than water storage to the riparian areas. The extensive sophisticated water system consists of a variety of water diversion facilities. The continuous operation with effective coordination and management greatly manifests Huizhou people’s wisdom.

(1) Weir system

Huizhou Region has a long history of the construction of weirs, which can be traced back to the Wei and Jin Dynasties (220–420). “堨” (a Huizhou idiom [34] and also written as “碣”) means earth-made weirs used to contain water[39]. “堨” was widely recorded in local journals, village chronicles and other historical documents. For instance, Qimen County Chronicles in the Qing Dynasty (Tongzhi Reign) detailed the reasons for irrigating weirs construction in flat riverine areas—the farmland in fields was often far away from valleys, so it would be more convenient to convey water from rivers and streams instead of ponds in the mountain[40]; Xiuning County Chronicles[41] in the Qing Dynasty (Daoguang Reign) and the Huangyang Village base map in Qimen Fang Clan Genealogy in the Qing Dynasty (Tongzhi Reign) (Fig. 9) both had records about “堨.” Technically, “堨” in Huizhou Region can be understood as a full water diversion system including the dams, weirs, and other facilities built in rivers to raise water level, diverts water into canals, and then to irrigate farmland or be used as part of village water systems. This means that dams, weirs, and other water facilities are critical to the system’s operation to convey irrigation water to the fields from rivers (Fig. 10).

Fig9. Huangyang Village base map in Qimen Fang Clan in the Qing Dynasty (Source: Ref. [73])

Fig10. The map of the southern and northern canals of Lyu’e Weir in the Qing Dynasty. The weir system is multi-leveled, consisting of landscape elements such as weirs, dams, ponds, and ditches (Sources: Records of the Lyu’e in She County and Google satellite map).

Today, such water diversion systems are still in use in Huizhou Region. For example, the Lei’e, Tiao’e, and Long’e water diversion systems in Xixinan Village by the Fengle River form the main structure of the village water system, ensuring villagers’ domestic water use (Fig. 11). However, in some areas such as the former Lyu’e irrigation zone in Xixinan Village, most land currently is occupied by the urban construction and most canals are transformed into concrete ones that no longer serve for irrigation. Modern infrastructure such as dams and reservoirs built on the upper reaches of Fengle River, together with these traditional water diversion systems, maintain the water supply of Fengle River Basin and improve the regional resilience to droughts and floods.

Fig11. Lyu’e Weir nearby Xixinan Village, Huizhou District, Huangshan City.

(2) Ditch system

“水圳”⑤ can be understood as a ditch system built for certain purposes—agricultural irrigation and guaranteeing domestic water use[42], roughly (Fig. 12). Agricultural ditch systems are built along farmland ridges, serving as a part of pond- or weir-system, especially for rice irrigation. Domestic ditch systems are built along main street or paths in the village, linking up fish ponds, weirs, and shuikous and connecting the rivers outside the village. Today, ditch system is still an important component to the artificial water system in Huizhou Region; many ancient ditch systems, at different locations or in varied elevation, are well preserved and still serving domestic water in villages (Fig. 13, 14).

Fig12. The painting showing a ditch system passing through Dacheng Village, She County, in the Qing Dynasty (Qianlong Reign) (Source: Ref. [75])

Fig13. Ditch and dock in Xixinan Village

Fig14. Irrigation ditch system in Fuling Town

(3) Connecting-tube system

The Xin’an Zhuzhi Poem narrates that ancient Huizhou people built spring water conveyance systems to irrigate gardens by connecting bamboo tubes, which often go across towns and villages[43]. Shoushi-Tongkao explains the working mechanism of “连筒”—a local irrigation method[43] that is still in use by now[33] (Fig. 15)—that Huizhou people used big bamboos and hallowed out the knots inside, then connecting the bamboo tubes with each other to take water from far-away sources and convey water continuously[33]. Nowadays, local people build such low-tech connecting-tube systems with modern materials. For instance, locals connect and elevate water pipes to deliver water from river dams into farmlands in the nearby highlands (Fig. 16).

Fig15. The illustration of “连筒” (Source: Ref. [33])

Fig16. Irrigation connecting-tube system near Gutan Village, Wuyuan County

(4) Frame slot

Defined as a wooden bridging trough by Shoushi-Tongkao, “架槽” usually jointly builds by several families to convey water from far-away sources to settlements that are no height limits (Fig. 17)[33]. Various small wooden or stone troughs are preserved nowadays and still in use in Huizhou Region (Fig. 18, 19). With advanced water diversion techniques, now long-distance troughs are mostly constructed with concrete or other modern materials to enhance conveyance effectiveness.

Fig17. The illustration of “架槽” (Source: Ref. [33])

Fig18. Wooden trough in Kengtou Village, Wuyuan County

Fig19. Stone trough in Shangyantian Village, Wuyuan County

3.1.1.3 Digging wells for drinking

Before the 1990s, people in Huizhou Region and many other Chinese regions mainly took drinking water by digging wells. Wells in Huizhou Region are usually 3 ~ 5 m in depth, 7 m the deepest. The groundwater level in some mountainous areas is quite shallow, where artesian wells or pools can be created for irrigation or drinking[44]. Locals would maintain the wells regularly, for example, villagers of Shangzhuang Village in Jixi County clean the wells on 6th of June of Lunar Calendar annually (commonly known as “refreshing wells”)—they repair and cleanse the inner and outer wells, and assess the water safety by keeping and observing crucians in the wells[45].

Many ancient wells preserved in Huizhou Region, are indispensable parts of local water cultural landscapes. However, due to the popularization of tapwater, most wells are no longer used for drinking water intakes, and now become auxiliary water sources for villagers’ daily washing (Fig. 20, 21). In some villages, traditional wells are converted into hand-pressed wells or combined with pumping facilities to irrigate during droughts.

Fig20. Well in Shiqiao Village, Huangshan City

Fig21. Well in Jiang Village, She County

3.1.2 Water Resource Control and Disaster Prevention

3.1.2.1 Dikes

The She County Chronicles in the Republic of China period (1912–1949) succinctly explained the difference between “堤” (dike) and “坝” (dam) that the former intercepts and slows down the water flow, while the latter blocks and stops the flow to protect houses and farmlands from floods[46]. In Huizhou Region, dams are also often called “堨”[46], and dykes are collectively termed as “堤坝.” Although there are few dikes in Huizhou Region, the She County Chronicles values dikes and dams more than ponds and weirs, due to the huge impact of mountain floods on Huizhou people’s life and production[46].

3.1.2.2 Groyne

The She County Chronicles also explains “水射” (groyne) as a water facility that is designed to change the direction of water flow to mitigate the effect and erosion of water[46]. Groyne, also called “防壍” in Huizhou dialect[46], is built at the confluence of the main river course and tributaries to avoid or mitigate river bed branching [46]. Like spur dikes that widely used in the construction of modern water conservancy projects, traditional groynes also embody local people’s wisdom in practicing hydraulic laws. For example, recorded by scholar Ling Yingqiu in the Qing Dynasty, the residents in She County, lived nearby the Fangxi River with flooding problems, dredged river course and diverted water flows to avoid potential floods. The purpose and method of construction are similar to those of groynes[47]. Today, there still retains the practice of building groynes to strengthen embankments or protect house bases in Huizhou Region (Fig. 22).

Fig22. Groyne beside Huixiu Bridge in Xunjiansi Village, Wuyuan County: use stones to build the river bank into the river to minimize the impact of water flow by change its direction.

3.1.2.3 Water-powered trip-hammer

Until the 1960s, “水碓” (water-powered trip-hammer) had been a common tool to pound rice and extract oil throughout the region[48] (Fig. 23). It is stated in Shoushi-TongKao that such trip-hammers can be installed at any riverine area[33] simply by building weirs in the river to convey water into the site. Traditional water-powered trip-hammer was an important tool in Huizhou people’s daily activities. In the Qing Dynasty, poet Wang Youdun praised the agricultural production scene when the locals employed water-powered trip-hammers along waterfronts in his poem[49].

Fig23. The illustration of “水碓” (Source: Ref. [33])

However, the use of water-powered trip-hammers often led to conflict of interest, because the construction of water-powered facilities requires diverting water from river by weirs or dams, which would intervene normal water flows and often causes river channel congestion and shipping obstruction. For instance, in the Qing Dynasty (Kangxi Reign), the usage of water-powered trip-hammers in the lower stream in Jinzhuzhou, Qimen County directly impacted that usage in the upper steam[50]. In another case, to solve the conflict between residents’ daily use of water-powered trip-hammers and agricultural irrigation, both supported by the Lyu’e Weir, She County stipulated that the former should be suspended during the irrigating months, and inscribed related specific regulations on steles[51]. Nowadays, traditional water-powered trip-hammers are replaced by modern farm equipment such as rice milling machines, and have been preserved as a cultural resource that can be developed into experiential or parent-child educational tourism (Fig. 24).

Fig24. The water-powered trip-hammer is still in use in the scenic area of Raonan Village, Jingdezhen City.

3.1.3 Building Settlements

3.1.3.1 Shuikou

“水口” (shuikou) is a key node in settlement landscapes of Huizhou Region. In the respect of local Feng-Shui ideology, there is a tradition to build structures (such as bridges, tea pavilions, and inns) or plant trees over shuikous to protect the spirit and fortune of the whole town[52]. In other words, shuikous not only simply work as water facilities, but also are significant to the Feng-Shui of settlements in the region and the regional landscape systems. There are various forms of shuikous, including bridges, pavilions, temples, weir, dams, and water-powered trip-hammers, integrating productive, living, and ecological functions together. The hierarchy of shuikous is determined by their locations over the river system. For example, the Yuliang-Dam shuikou located on the upper reaches of the Xin’an River was the primary shuikou of the ancient capital of Huizhou Region, and the Shengao-Pagoda shuikou on the Fengle River in Yansi was a county-level shuikou. The rest are town- or village-level shuikous and mostly located at the tail-parts of village water systems (Fig. 25). Considering different standards, shuikous in a village can also be classified into secondary and tertiary, large and small, inner and outer ones, which are usually maintained by donations from villagers. Historical local chronicles and other documents have a large amount of records of such donations[53][ 50].

Fig25. Shichun-Pavilion Outlet and Wenchang Pavilion in Wuyuan County

Regrettably, only few shuikous have remained by now, and the locals’ Feng-Shui ideology has also dramatically changed[54]. Meanwhile, the culture of shuikous in Huizhou Region has continued over centuries. Yantian Village of Wuyuan County, for example, issued its current village regulations on the shuikous protection, which also helped protect the ecological resources such as shuikou forests. The well-preserved shuikous now become valuable landscape resources for tourism throughout the region, such as the wooden bridges, low weirs, and maple forests at the shuikous in Xixinan Village in Huangshan District of Huangshan City (Fig. 26, 27).

Fig26. Well-preserved Chaguan Outlet landscape in Wuyuan County

Fig27. Water outlet landscape in Xixinan Village, Huangshan City

3.1.3.2 Patio

The patio is a vernacular water-structure in Huizhou architectures. In addition to increasing ventilation and sunlight access, patios also facilitate rainwater collection and storage. Locals hold that gathering water can be a way to keep fortune—thus roof runoff would be gathered through gutters and flow into the pool inside the patio(Fig. 28) or water tanks (Fig. 29) on the ground. Overflow would be collected by covered catch basins or drainage ditches[55][56]. Nowadays, in traditional Huizhou residential buildings, water tanks are still placed in the patios to collect rainwater in case of fire emergence.

Fig28. Patio of old settlement in Xixinan Village, Huangshan City. The design of sloping roofs and pitched eaves helps collect rainwater.

Fig29. Rainwater tubes and water tanks in the patio of the dwellings in Kengtou Village, Wuyuan County

3.2 Components of Huizhou Water Cultural Landscapes in Huizhou Region

3.2.1 Settlement Water Cultural Landscape

Huizhou settlement, as a major tangible part of Hui cultural legacy, is often built close to rivers. The settlement water cultural landscape includes all kinds of elements of water cultural landscapes, and is seen as the most culturally typical in the regional landscapes. In the Ming and Qing Dynasties, water system management was fundamental in the construction of Huizhou settlements. Domestic water was usually sourced from rivers, and kept flowing throughout the village water system, which went through the water inlets, multi-level ditch systems and/or a series of ponds, and finally rejoining the river from shuikous. These man-made water systems, together with the surrounding forests and water systems, form a settlement water cultural landscape system of the region (Fig. 30).

Fig30. Map of Xidi Village in Yi County in 1821 (Source: Ref. [73])

Huizhou people foster their living water habits and norms under such settlement water cultural landscapes: the major ditch area is the busiest living place to many local settlements, where residents do the laundry, wash vegetables, gather, and communicate. Domestic sewage drains through the ditch and discharges outside the village to ensure the water safety of the village. The tradition of time-sharing water usage developed in the Ming and Qing Dynasties[11] has also remained till now. For example, residents in Xixinan Village of Huangshan City still hold the norm that no washing in ditches in the morning. These inherited traditions are an intangible heritage by the continuity of water cultural landscapes.

3.2.2 Farmland Water Culture Landscape

The farmland resource in Huizhou Region is limited historically. Sitting in the mountainous area of southern Anhui Province, with a dramatically high and steep terrain, Huizhou is prone to floods and droughts[37] that if without rainy days for several days may cause drinking water shortage problem[37][38]. The geological conditions in Huizhou are very low in adaptability to droughts and floods. Huizhou people have continuously built water conservancy projects to transform and improve the farming environment, which is critical to their survival and development.

It can tell from the local Fish-scale Field Maps that the farmland water culture landscape is mainly composed of irrigation facilities such as ponds, weirs, and ditches. The maps plot the exact locations and areas of various types of farmlands (Fig. 31), Due to the disparity of topographical and hydrological conditions, the amount of ponds, weirs, and dams varied, and the land price of which is determined by how difficult the site can obtain irrigation water. Overall, ponds and weirs are the greatest elements in the regional farmland water cultural landscape, forming a pond–weir landscape pattern over the past dynasties. The effective water system management ensures the sustainability of farmland water system, and preserves the regional identity of farmland water cultural landscapes.

Fig31. Fish-scale Field Maps in Xiuning County in the Ming Dynasty (Wanli Reign) outlined the distribution of ponds (in blue) (Source: Ref. [77])

3.2.3 River Cultural Landscape

Huizhou Region has a diverse river network—rivers and streams link up cities, towns, and villages. Historically, Huizhou Region had business connections and commercial connections and exchanges with Suzhou and Hangzhou by shipping along the Xin’an River; Huizhou Region had also suffered from food shortage, and grain transit from other places also relied on water transport, which mattered Huizhou people’s livelihood. The locals usually built dams on rivers to raise water level and built docks to ensure shipping, establishing transportation and goods hubs including the Yuliang Dam Dock, which is successively funded by officials and squires and served as the overall water outlet of Huizhou Region. The water transport and dock culture (Fig. 32) has greatly enriched the regional river cultural landscapes.

Fig32. The shipping scene of Xin'anguan Dock (near Yuliang Dam) is recorded in the repaired genealogy tomb maps of Xu Clan in She County (Source: Ref. [78]).

3.3 Types of Water Cultural Landscapes in Huizhou Region

In Huizhou Region, people’s production and living activities mainly happen in valleys, hills, and basins (Fig. 33), and regional water cultural landscapes can be roughly divided into three types correspondingly, which also witness a disparity in the distribution of different landscape components and elements according to varied geographical conditions.

Fig33. The mountainous and hilly terrain of Huizhou Region. The map is generated by the platform Geospatial Data Could, according the topographic data of most areas in Huangshan City, and the DEM data of Jixi County and Wuyuan County.

3.3.1 Valley Water Culture Landscape: Village Water Security Pattern

To most counties such as Qimen, Wuyuan, and Jixi, valleys accommodate local people’s living and farming activities. In the narrow valley areas, rivers connect settlements, farmlands, and other landscape components that form a typical village water security pattern (Fig. 34). Locals raise water level by building dams, and then divert water through ditch systems to meet the needs of farmland irrigation and domestic water use. In the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Huizhou people regulated the height of dams, dredged canals, maintained the landscape of shuikous, and protected mountains and forests by clan norms, gradually establishing the water security pattern of the village. In the 1950s, deforestation often led to severe soil erosion, which further caused the river obstruction heavily impacting water transportation and the dam/weir usage in valley areas. Such problems were progressively alleviated after the implementation of the national forestation policy, and the well-preserved historic villages in valley areas have become important cultural heritages (Fig. 35). Today, Huizhou Region needs to establish a sound water security pattern that ensures residents’ domestic and agricultural water use and be resilient to floods.

Fig34. Typical valley water cultural landscape in Jixi County in the Qing Dynasty (Guangxu Reign) (Source: Ref. [73])

Fig35. Huang Village in Wuyuan County, located in the valley area.

3.3.2 Hill Water Cultural Landscape: Production Water Security Pattern

Low mountains and hilly areas occupy a larger area of Huizhou Region than other terrains, and also accommodate local people’s most agricultural activities. The locals make full use of every bit of space to build settlements and reclaim farmlands. Villages are usually built on flat riparian areas where domestic water can be more easily to obtain from rivers, while the crop fields on the hills are often far away from rivers, so the water is mostly sourced from mountain springs or rainfalls, where ponds are even more important to the water storage and irrigation. The locals practice dryland farming or create woodland on uplands, and at the same time build multi-layered pond systems at cols to collect hill runoffs, then convey the rainwater by ditches, to irrigate the paddy fields in lowlands (Fig. 36).

Fig36. A diagrammatic scheme of typical hilly water cultural landscape

Different from valley areas, hilly areas often homes a city or a township. For example, the hilly landform of Weiqiao Township in Xiuning County accommodates about 1,100 hm2 of paddy fields, 35 hm2 of drylands. In addition to oil crops, tea gardens, orchards, and mulberry gardens, it also has six plantation bases—including economic fruit forests, forests, tobacco leaves, water-surface aquaculture, organic tea, and seedlings⑥ (Fig. 37)—which are highly dependent on the effective water management and utilization (Fig. 38).

Fig37. The overall topography map of the west of Weiqiao Township, Xiuning County, recorded in the Fish-scale Field Maps in the Ming Dynasty (Wanli Reign) (Source: Ref. [77])

Fig38. Ponds in the seedling base in the hilly areas of Weiqiao Township, Xiuning County, ensure the irrigation water supply.

In Huizhou Region, the hilly areas, especially hillsides, are also suitable for farming. In spite of the undulating topography, there are more available lands for cropping in-between hills, where the locals build ponds to collect rainwater and runoffs in order to irrigate farmlands, forming a pattern with multi-layered irrigation ponds (Fig. 39). For example, in Fuling Town of Jixi County, people plant paddy along the flat riverfronts, and reclaim farmlands on hillsides, and construct a large number of multi-layered ponds to store irrigation water that are connected by ditches for an effective management of water resource. At higher hillsides bamboo forests were planted that do not require additional irrigation and can provide food and incomes for the locals; the hilltop is covered by natural forests, and on some ground ferns, an indigenous food in Huizhou Region, grow. Thus, the production water security pattern of hilly areas is established with the layered structure of paddy fields, dry-wet mixed farmlands, bamboo forests, and mountain forests.

Fig39. Diagrammatic section of typical hill water cultural landscape

In the middle and late Qing Dynasty, Huizhou Region’s hilly areas had suffered from severe soil erosion. Damages by slum dwellers to mountain vegetation and the planting of large areas of tea and corn[57]~[59] made the fragile soil layer prone to storms and floods. Since the 1950s, vegetation in the hilly areas was heavily destroyed, resulting in frequent geological disasters in the following two decades. After the 1980s, the vegetation coverage in hilly areas has been greatly improved as the result of the implementation of forestation as well as soil and water conservation policies. Typically, through continuous ecological restoration, Fuling Town of Jixi County has developed its tourism and been selected as one of the first famous tourist towns in Anhui Province (Fig. 40).

Fig40. Hill water cultural landscape in Fuling Town, Jixi County.

3.3.3 Basin Water Cultural Landscape: Urban Water Security Pattern

The basin is the most suitable area for agricultural production, urban construction, and economic development of the region. Landscape components, including settlements, farmlands, and rivers, interweave, and many famous towns and villages have emerged. Since the Ming and Qing Dynasties, most cities and towns had been located in relatively flat basins (Fig. 41), and such an urban construction pattern remains till now. People living in the riverine areas could easily source irrigation water from the river, while for those who lived far away from the river had to excavate ponds to store rainwater (Fig. 42), in addition to building water diversion systems. Among them, the pond system was used to reduce flood peaks, and the weir systems were employed to manage water resource allocation, enabling the basin resilient to droughts and floods in the Ming and Qing Dynasties when engineering techniques were inadequate.

Fig41. The overall map of hills and streams in the ancient Huizhou Capital (Source: Ref. [38])

Fig42. Typical basin water cultural landscape in She County

During contemporary urbanization, most farmlands in basin areas have been replaced by modern buildings and concrete channels. The reduction of arable land, the abandonment of ponds, and the increase of hardened surfaces have intensely changed the historical water security pattern, causing frequent urban waterlogging problems. Re-constructing an urban water security pattern is vital to solving contemporary urban water issues what Huizhou Region is facing.

3.4 The Overall Identity of Huizhou Region’s Traditional Water Cultural Landscapes Defined by Pond–Weir–Shuikou Systems

Pond, weir, and shuikou systems are the most distinctive and representative elements of the water cultural landscapes in Huizhou Region, together narrating the region’s historical stories. They are widely found in the settlement water cultural landscapes (Fig. 43); in addition, pond and weir systems are jointly employed in the farmland irrigation system to serve different water use purposes; the river cultural landscape system links all levels of shuikous with ponds and weirs—the main river course and tributaries determine the hierarchy of shuikous, as well as the distribution of ponds and weirs, shaping the identity of the regional culture centered in the Xin’an River Basin.

Fig43. The settlement map of Fan Clan Genealogy in Xiuning County in the Ming Dynasty (Wanli Reign) (Source: Ref. [73])

In terms of landscape scale, pond, weir, and shuikou systems compose the water security patterns for valleys, hills, and basins. In the construction process of settlements, the distribution of shuikous usually prioritizes water system planning; in the valley areas, more water diversion systems are built to meet villagers’ domestic and irrigation water needs; in hilly areas, more ponds are created to ensure agricultural production; while in basins, the construction and pattern of pond and weir systems is determined by the river.

Therefore, pond, weir, and shuikou systems embody the characteristics of Huizhou Region’s traditional water cultural landscapes at varied scales. The water cultural landscape in Huizhou Region should be interpreted as a systematic notion, in which all landscape elements such as ponds, weirs, and shuikous are interdependent and closely related with human activities, and require long-term maintenance and management. It is also fundamental to Huizhou people’s life and Huizhou culture.

4 Contemporary Value of Traditional Water Cultural Landscape in Huizhou Region

4.1 Supplement for Farmland Water Conservancy Construction and Management

In the early years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Huizhou people revitalized the remaining ponds and weirs to meet production and daily needs, which greatly alleviated the shortage of agricultural irrigation facilities under the tough situation at that time. Later, there was a movement of learning from traditional management experience of ponds and weirs: In the 1950s and 1960s, the Water Conservancy Bureau of Huangshan City had organized a series of study activities about the water management of ancient facilities such as Lyu’e Weir and Baonan’e Weir, and stipulated modern regulations on water use by referring to historical practice⑦.

For ages, most rural areas in China have faced the inadequacy in farmland water conservancy facilities[60]. Since the implementation of the Policy on Accelerating the Reform and Development of Water Conservancy by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council in 2011, governments at all levels have increased funding in farmland water conservancy. However, a large proportion of funding allocated in anti-seepage engineering projects and pump station construction, less in smaller farmland water systems improvement based on ponds and weirs[61]. The existing management regime could not effectively support farmers’ agricultural production, and the coordination at all levels was insufficient[62]. At present, small-sized water conservancy facilities in Huangshan City are almost collectively owned by villagers and funded by the government⑧, but the locals have low participation and the water conservancy agencies are facing severe shortage of funds⑨. Water cultural landscapes, consisting of elements such as ponds and weirs, have a variety of landscape forms with relevant different management systems and sustainable mechanisms[63]. It can draw lessons from the management wisdom in traditional water culture landscapes, e.g., how to improve the enthusiasm of managers and local farmers; how to establish varied management modes for water conservancy facilities with different landscape forms and functions; and how to build a multi-level networked management regime.

4.2 The Foundation of Sponge Land Construction

A serious flood attacked Huizhou Region in July, 2020, which led to water logging in Xiutun Basin and the upper reaches of Xin’an River and even affected the holding of the National College Entrance Examination in She County. The reason might be that the city has witnessed a decrease of small ponds and an increase of impervious surfaces, resulting in the huge loss of water cultural landscapes, especially in the adaptation and resilience to droughts and floods. This forces us to reconsider and systematically reexamine urban flood control planning at regional and national scales.

“Sponge City” is an important theory to respond to the impact of droughts and floods in China’s monsoon climate zones. It needs to carry out the construction of sponge infrastructure integrated with landscapes at varied scales, and upgrade Sponge City construction to Territorial Sponge construction, where the ancient ecological experience and wisdom in traditional water cultural landscapes can be absorbed as part of key techniques[64]. Particularly, Huizhou people have accumulated such valuable practice experience in water resource management and to droughts and floods[65]. Various landscape elements and types in the regional traditional water cultural landscapes with a majority of small-sized water facilities, can be integrated and employed in different geographical conditions such as valleys, hills, and basins. These facilities can also be used to strengthen the regional resilience to floods and droughts, so as to enhance the overall adaptability of water environment. Huizhou Region’s traditional water cultural landscapes remain as resilient infrastructures and landscape heritages at varied scales[64], the foundation for sponge countryside and sponge city construction[66], and an important ecological infrastructure for rural revitalization[67].

4.3 Heritage Resources and Potential of Cultural Tourism Development

The water cultural landscape in Huizhou Region preserved over centuries is a typical cultural heritage. Specifically, shuikou landscapes are of prominent tourism values; ponds, weirs, and other farmland irrigation facilities can become suitable sites for nature education and fieldwork; linear river corridors are also of potential to develop water sports tourism. For example, Lyu’e Weir and its shuikou located near Xixinan Village in Huangshan City now has become a representative landscape in the town, where tourists can learn about the ancestors’ wisdom of water management, and enjoy nature education programs. This emerging tourism also helps promote local economic and social development[68]. These cultural resources need in-depth exploration to leverage their potential in rural cultural tourism and the revitalization of rural culture.

5 Conclusion

This paper proposes the concept of “water cultural landscape,” that is, the landscape formed through humans’ environmental alteration during water activities—including how people use, transform, and manage it. The traditional water cultural landscapes in Huizhou Region have developed over hundreds of years, and reflect the locals’ wisdom in sustainable water use. The water cultural landscape in Huizhou Region should be interpreted as a systematic notion, in which all landscape elements such as ponds, weirs, and shuikous are interdependent, composing the water security patterns for valleys, hills, and basins. It also lays the foundation of the regional culture and resources[68], and propels the rural industrial and cultural revitalization. Intangible heritages including water management experience could not only ensure the sustainability of the traditional water cultural landscape, but also offer references for contemporary protection and utilization of various cultural heritages.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the officials of Water Conservancy Bureau of Huangshan City, Huangshan City Archives, Jixi County Water Affairs Department, Jixi County Archives, Wuyuan County Water Conservancy Department, Wuyuan County Archives, and other agencies for their great help in site investigation and data collection. Thanks to Professor Cui Haiting of Peking University, Professor Tan Xuming of China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Mr. Lu Genping, Director of the River Chief System Department of Huangshan Water Resources Bureau, and the anonymous peer reviewers for their valuable comments on this paper. Thanks to Dr. Lin Haowen, Dr. Yun Hong, Dr. Zheng Changhui, and others for their help in this research. Finally, thanks to Ms. Tina Tian, editor at Landscape Architecture Frontiers journal, for her editorial suggestions to the paper.

参考文献:

[1] Chen, M, (2013). Reflection related to water ecological civilization construction. China Water Resources, (15), 1-5.

[2] Tang, K. (2013). Discussion on concept and assessment system of aquatic ecological civilization. Water Resources Protection, 29(4), 1-4. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-6933.2013.04.001

[3] Wang, J., & Hu, P. (2013). Studies on evaluation system of water ecological civilization. China Water Resources, (15), 39-42.

[4] Liu,F., & Miao, W. (2016). Study on system model construction of water ecological civilization construction elements. China Population, Resources and Environment, 26(5), 117-122. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-2104.2016.05.014

[5] Wang, H. (2016). Theoretical basis and key problems of water ecological civilization construction. China Water Resources, (19), 5-7.

[6] Yu, K. (2019). Large scale ecological restoration: empowering the nature-based solutions inspired by ancient wisdom of farming. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 39(23), 8733-8745. doi:10.5846/ stxb201905311146

[7] Yu, K. (2018). Green Infrastructure Through the Revival of Ancient Wisdom. Landscape Architecture Frontiers, 6(3), 6-11. https://doi.org/10.15302/J-LAF-20180301

[8] Zhou,B., Tan, X., & Wang, M. (2013). The conditions, issues, and strategies of the preservation and utilisation of water culture heritage in water scenic zones. Water Resources Development Research, 13(12), 86-90. doi:10.13928/j.cnki. wrdr.2013.12.021

[9] Wang, J., & Lu, Y. (2012). Discussion about the value and preservation and development of water culture heritage in China. Water Resources Development Research, 12(1), 77-80. doi:10.13928/j.cnki.wrdr.2012.01.004

[10] Bian, L. (2017). A brief history of development of Hui studies in 20th Century. Hefei, China: Anhui University Press.

[11] He, W. (2010). Studies on Water Systems and Their Construction Techniques in Huizhou Villages. Beijing, China: China Architecture and Building Press.

[12] Yu, K. (2018). "Mountainous Village Society" and the Transformation of Water Management: A Case Study of Huizhou Lv-hui (1127-1930) (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from CNKI database.

[13] Wu,Y. (2007). The disasters in Huizhou during Ming and Qing dynasties and the social response (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from CNKI database.

[14] Cheng, L. (2010). Research on Urban Waterfront Landscape Culture. The Border Economy and Culture, 2010(11), 74-75

[15] Dong, J. (2009). The Study of Dock Design and Renovation of Wuhan Waterfront Culture Landscape (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from CNKI database.

[16] Liu, J. (2014). Expression of regional culture in urban waterfront landscape (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from CNKI database.

[17] Su, Q. (2004). A Study on the Types of Tourists and Their Experience Quality—A Case Study of Zhouzhuang. Scientia Geographica Sinca, 24(4), 506-511. doi:10.13249/j.cnki. sgs.2004.04.506

[18] Xu, H., & Cui, F. (2008). The protection and utilisation of water cultural heritage in Guangzhou. Yunnan geographic environment research, (5), 59-64.

[19] Lyu, J. (2019). Research review and discussion on water culture theory. China Flood and Drought Management, 29(9), 51-60. doi:10.16867/j.issn.1673-9264.2019140

[20] Wang, D. (2000). On the Relationship Between Water Culture and Urban Planning. Urban Planning Forum,127(3), 29-36.

[21] China Water Literature and Art Association. (2008). Introduction to Chinese Water Culture. Zhengzhou, China: The Yellow River Water Conservancy Press.

[22] Tan, X. (2012). Explanation of the definition, characteristics, type and value for water culture heritage. China Water Resources, (21), 1-4.

[23] Yun, H., & Lin, H. (2021). The Conservation and Regeneration Approach of Historical Village under Dynamic Perspective of Cultural Landscape. Urban Planning International. Advance online publication. Retrieved from https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/ detail/11.5583.tu.20210125.1444.003.html

[24] Dickinson, R. E. (1980). The Makers of Modern Geography. Beijing, China: The Commercial Press.

[25] Sauer, C. O. (1941). Foreword to historical geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 31(1), 1-24.

[26] Tang, M. (2000). The Inventory and Progress of Cultural Landscape Study. Progress in Geography, 19(1), 70-79. doi:10.11820/dlkxjz.2000.01.011

[27] Sauer, C. O. (2008). The morphology of landscape. The Cultural Geography Reader (pp. 108-116). New York, NY: Routledge.

[28] Wang, F., Jiang, C., & Wei, R. (2017). Cultural landscape security pattern: Concept and structure. Geographical Research, 36(10), 1834-1842. doi:10.11821/dlyj201710002

[29] Li, H., & Xiao, J. (2009). Analysis on the Types and Composing of Cultural Landscapes of China. Chinese Landscape Architecture, 25(2), 90-94. doi:10.3969/ j.issn.1000-6664.2009.02.021

[30] Yu, K. (2002). Meanings of Landscape. Time + Architecture, (1), 45-17. doi:10.13717/j.cnki.ta.2002.01.002

[31] China Water Conservancy Zoning Compilation Team. (1989). China Water Conservancy Zoning. Beijing, China: Water Resources and Electric Power Press.

[32] Liang, Z. (2013). Water disasters and society of Huizhou during Ming and Qing Dynasties. Journal of Anhui University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 37(2), 112-118.

[33] Shoushi-Tongkao. (1956). Beijing, China: Zhonghua Book Company.

[34] Wang, L. (2000). Wang Li Ancient Chinese Dictionary. Beijing, China: Zhonghua Book Company.

[35] Wang, Q. (2017). The research on local Fish-scale Field Maps in Huizhou in Qing Dynasty. Hefei, China: Anhui Educational Publishing House.

[36] Ge, T. (1998). Jixi County Chronicles. Hefei, China: Huangshan Publishing House. Retrieved from http://www.weidongqu. com/Article/131.html

[37] Ma, B., & Xia, L. (1827). The Chorography of Huizhou (Daoguang Reign).

[38] Peng, Z., & Wang, S. (n.d.). The Huizhou official Chronicles (Hongzhi Reign).

[39] Xie, L. (2015). Viewing the Pronunciation of word ”堨” in Hui Language. Fangyan, (1), 55-57.

[40] Zhou, R., & Wang, Y. (1873). Qimen County Chronicles (Tongzhi Reign).

[41] He, Y., & Fang, C. (1815). Xiuning County Chronicles (Daoguang Reign).

[42] Hu, M., & Zhao, Z. (2012). Slight Exploration of the Theoretical Method to Conservation and Rehabilitation About Historic Shuizhen Landscape: A Case of Historic Shuizhen Landscape in Historic City Jixi. Urban Studies, 19(05), 9-12, 17.

[43] Ni, W. (1890). The Poem of Chuo Village.

[44] Shu, Y. (2012). Yi County Chronicles. Hefei, China: Huangshan Publishing House.

[45] Editing Committee of Shangzhuang Village Chronicles. (2009). Shangzhuang Village Chronicles. Xuancheng, China: Xuancheng City Press and Publication Bureau.

[46] Shi, G., & Xu, C. (1937). She County Chronicles.

[47] Ling, Y. (2018). The Collection of Essays of Shaxi. Wuhu, China: Anhui Normal University Press.

[48] Liang, Z. (2013). On the Shuidui Industry in Huizhou during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Historical Research in Anhui, (3), 100-107. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1005-605X.2013.03.014

[49] Wang, Y. (n.d.). The Collection of Poems of Songquan.

[50] A, F. (2016). Litigation Documents from Huizhou During the Ming and Qing Periods. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Classics Publishing House.

[51] Lyu’e Rules. (n.d.). The Chronicle of Lyu’e in She County.

[52] Wang, Z. (2011). A Socio-historical Study of Villages in Huizhou Since the Ming and Qing Dynasties: Focusing on Newly Discovering Rare Folk Literature. Shanghai, China: Shanghai People's Publishing House.

[53] Ge, Y., & Jiang, F. (1925). The Amendment of Wuyuan County Chronicles.

[54] Ge, F. (2016). The Vicissitude Process and Application of Shuikou and Village Entrance in Huizhou (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from CNKI database.

[55] Chen, W. (2000). The Viewpoint of Feng Shui in Hui Zhou Traditional Residence (Village). Huazhong Architecture, 18(02), 123-126. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-739X.2000.02.040

[56] Huang, C. (2000). The preliminary studies on cultural landscape of Huizhou. Geographical Research, 19(3), 257-263. doi:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0585.2000.03.005

[57] Liang, Z. (2014). The new discovery of Huizhou corn economy in Qing Dynasty: Based on documents. Journal of Anhui University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 38(06), 105-110. doi:10.13796/j.cnki.1001-5019.2014.06.015

[58] Wang, B., & Zhu, G. (2019). In the Name of a New Crop: A Reexamination on the Movement to Evict the shed People of Huizhou during the Qianlong and Jiaqing Reign. The Qing History Journal, 113(1), 77-93.

[59] Liang, Z. (2009). Contract and people’ livelihood: the thought of the permanent existence of the shed people in Huizhou during the Qing Dynasty. Historiography Research in Anhui, (3), 70-74. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1005-605X.2009.03.009

[60] Gong, Q., & Guo, L. (2011). Was the Water Scarcity in Southwest China a “Natural Disaster” or “Human-made Disaster”?. China Soft Science Magazine, (9), 108-121. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-9753.2011.09.012

[61] Cai, R. (2015). Maintaining Effect and Funding Willingness: Empirical Analysis on Collective Supply Willingness of Farmland Irrigation Canals in Rural Community. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University (Social Sciences Edition), 15(4), 78-86.

[62] Liu, Y., & Liu, Y. (2010). The Dilemma of the Current Water Conservancy for Farmland Irrigation. Exploration and Free Views, (5), 42-45. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-2229.2010.05.013

[63] Shi, S. (2020). Sustainable mechanism of water cultural landscape in Huizhou from Ming and Qing dynasty to the Republic of China (Doctoral dissertation). Peking University, Beijing.

[64] Yu, K. (2016). Ecology-based Water Management: "Sponge City" and "Sponge Land". Renmin Luntan`Xueshu Qianyan, (21), 6-18. doi:10.16619/j.cnki.rmltxsqy.2016.21.001

[65] Yu, K., Li, D., Yuan, H., Fu, W., Qiao, Q., & Wang, S. (2015). “Sponge City”: Theory and Practice. China City Planning Review, 39(6), 26-36. doi:10.11819/cpr20150605a

[66] Shu, J., Hu, L., Song, J., He, F., Hou, W., Feng, G., Cheng, S., … Tao, Z. (2020, July 1). The recurrence of “a view of the sea in cities”: how to prevent flooding in extreme storms [Online News]. Retrieved from http://www.xinhuanet.com/2020-07/01/ c_1126184062.htm

[67] Li, J., Xie, M., Hu, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Eco-agriculture and all-for-one tourism: The practice of rural revitalization in Wuyuan, Jiangxi. Resources Guide, (6), 56-57.

[68] Yu, K. (2017). New Ruralism Movement in China and Its Impacts on Protection and Revitalization of Heritage Villages: Xixinan Experiment in Huizhou District, Anhui Province. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 32(7), 696-710. http://dx.doi.org/10.16418/ j.issn.1000-3045.2017.07.004

[69] Zhou, S. (1999, March 24). From inscriptions on oracle bones to red comments written by Emperor Yongzheng. Beijing Daily.

[70] The Genealogy Book of the Dunmu Hall for Cheng Clan in Hongchuan, Jixi. (1923). Peking University Ancient Book Collection (X/977.05/2634). Peking University, Beijing, China.

[71] Yuan, P. (n.d.). Introducing five bulletins for citizens’ convenience after knowing about Huizhou. Mengzhai Collection. Retrieved from http://www.guoxuedashi.net/ a/21040a/266928l.html

[72] Liu, H., & Wang, Q. (2005). Relationship of Land in Huizhou. Hefei, China: Anhui Renmin Press.

[73] Bian, L. (2017). Huizhou Settlement Planning and Architecture Atlas. Hefei, China: Anhui Renmin Press.

[74] Guan, H., Li, Y., Peng, M., Shen, S., & Chen, Z. (2016). Application of DRASTIC Model Based on Mapgis and AHP in the Assessment of Groundwater Antipollution Capacity in the Central Area of Huangshan City, China. Earth and Environment, 44(2), 255-260. doi:10.14050/ j.cnki.1672-9250.2016.02.017

[75] The Branch Genealogy Book of Cheng Clan in Dacheng Village, Xinan (Qing Dynasty). Peking University Ancient Book Collection (SB/977.05/2617). Peking University, Beijing, China.

[76] Wuyuan Chronicles under Kangxi Reign. (2018). In Z. Wang (Eds.), The Collection of Rare Folk Literature in Huizhou. Shanghai, China: Fudan University Press.

[77] Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. (1993). Thousands of Years of Contracts in Huizhou: the Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties. Shijiazhuang, China: Huashan Literature and Art Press.

[78] The Amendment of the Genealogy Book of Xu Clan in Dongmen Area of Ancient She County. (1745). Peking University Ancient Book Collection (SB/977.5/0813). Peking University, Beijing, China.

[79] Anhui Province Development Department. (1933). The construction of Anhui in one year. Anhui, China: Anhui Development Department Publishing.

[80] Hu, J., & Wu, Y. (1989). The Brief Chronicles of Huizhou Region. Hefei, China: Huangshan Publishing House.

[81] Sun, W., Cui, Y., Lu, Y., Wu, D., Zhao, B., & Liu, F. (1936). The Research on Land-use Classification in Chongqing, Hubei, Anhui, and Jiangxi Region. Nanjing, China: Jinlin University Agricultural Economy Department.

[82] Anhui Local Records Editorial Committee. (1999). Water Conservancy Records in Anhui Local Records. Beijing, China: China Local Records Publishing.

[83] Wu, D., & Yu, Z. (1825). Yi County Chronicles (Daoguang Reign).

[84] Yu, K. (2017). Deep forms for beautiful China. Urban Environment Design, (107), 324-326.

[85] Yu, K. (2019). Lessons from the Social Form and Landscape Resilience of the Peach Blossom Land. Landscape Architecture Frontiers, 7(3), 4-7. https://doi.org/10.1530