Chinese landscape architect plants ancient solutions to a modern dilemma

近日,澳大利亚知名报刊悉尼先驱晨报(The Sydney Morning Herald)以“中国景观设计师以传统手段解决当代问题”为题,介绍了中国著名景观设计师俞孔坚带领的土人设计团队,在中国各地将生产与景观相结合的理念与实践。该文结合具体案例讲述了他的弹性景观与海绵城市理论,如何利用古老的农业智慧来解决中国最紧迫的问题之一——水敏感问题。

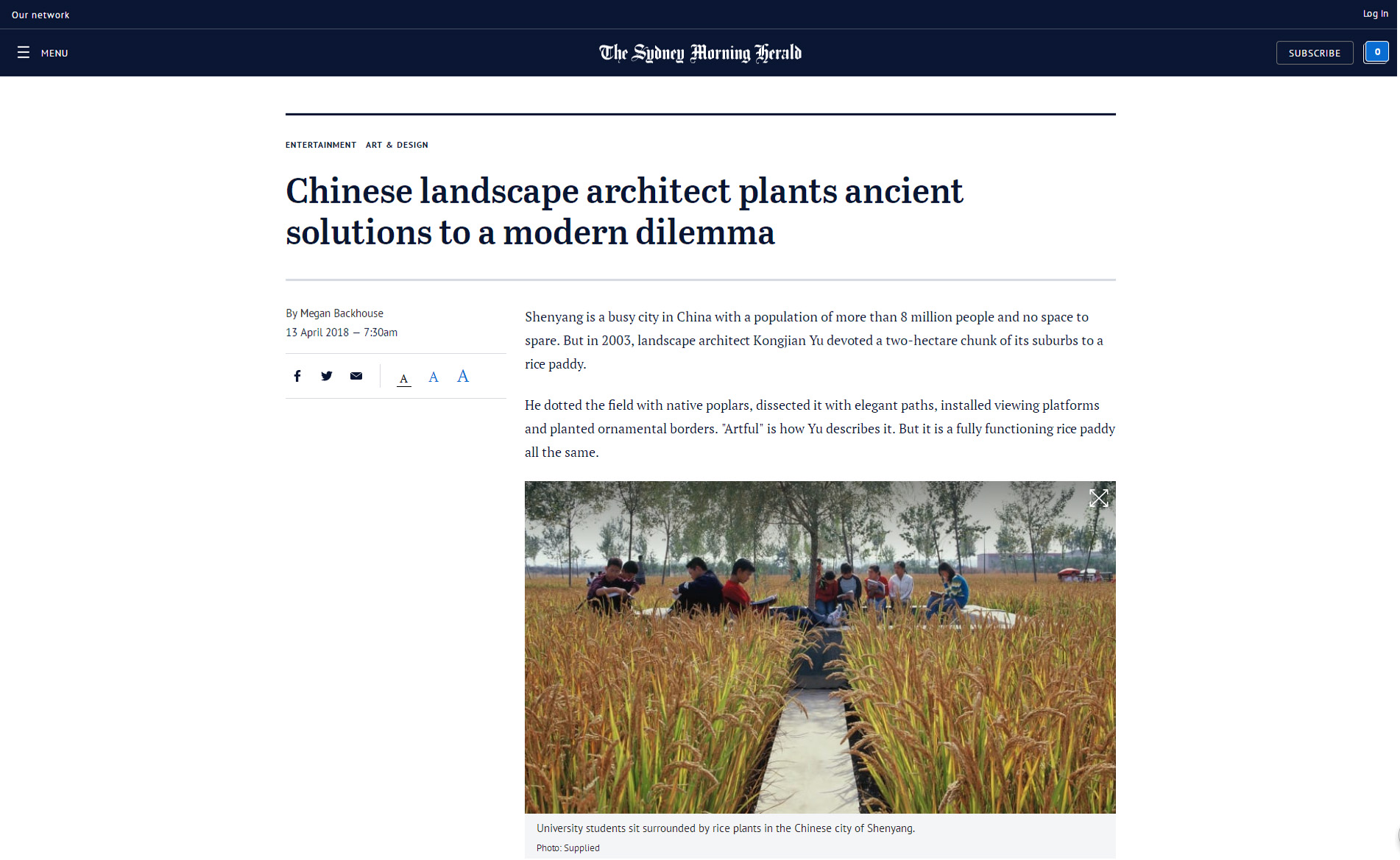

Shenyang is a busy city in China with a population of more than 8 million people and no space to spare. But in 2003, landscape architect Kongjian Yu devoted a two-hectare chunk of its suburbs to a rice paddy.

He dotted the field with native poplars, dissected it with elegant paths, installed viewing platforms and planted ornamental borders. "Artful" is how Yu describes it. But it is a fully functioning rice paddy all the same.

University students sit surrounded by rice plants in the Chinese city of Shenyang.

Photo: Supplied

It is also an example of how Yu uses age-old agricultural processes to tackle one of China's most pressing problems – the quantity and quality of its water.

Yu has spent the past 20 years designing landscapes that take China back in time. He uses plants to alleviate some of the problems – particularly around flooding – caused by China's rapid urbanisation over the past four decades.

Surrounded by high-rises, Kongjian Yu's ornamental park and farmland draws residents in Quzhou.

Photo: Supplied

In 2016, in the city of Quzhou (population 2.5 million), Yu took a deserted, mismanaged 32-hectare landscape and filled it with seasonal crops such as canola, sunflowers, buckwheat chrysanthemums, cosmos and poppies. Out came the site's concrete embankments and in went bioswales that allowed water levels to fluctuate naturally. By creating elevated boardwalks and flood-friendly pavilions, Yu lured the locals. The site, ringed by high-rises, has become a popular ornamental park and productive farmland.

It is a similar story with Yu's work on a deserted 1950s shipyard with wildly fluctuating water levels in Zhongshan (population more than 3 million). Yu reused industrial buildings, created terraces and introduced beds of native weeds to create an open green space where intermittent flooding is welcomed.

Water-sensitive design is happening in lots of countries, Australia included, but Yu told an audience at the National Gallery of Victoria's Melbourne Design Week that the scale of water-related problems in China has called for a particularly ambitious response. With a monsoon climate, China has short periods of concentrated rainfall, followed by months of dry weather. On July 21, 2012, a flash flood in Beijing killed 79 people and forced the evacuation of almost 57,000 people. A year earlier, severe storms in Beijing closed public transport.

While engineers designed thicker drainage pipes and installed stronger pumps, Yu says the scale of the problem calls for a different approach. He proposes something that is "simple, inexpensive and beautiful".

A viewing platform in Kongjian Yu's transformed Quzhou landscape.

Photo: Supplied

Through his company Turenscape, which has been involved with more than 1000 projects in 200 Chinese cities, Yu designs landscapes that he calls "sponge cities" – like a cloth, they retain and clean water. He keeps artificial infrastructure to a minimum, instead introducing ponds and channels through which water moves by gravity. He plants seasonal crops that suit available water levels or chooses plants that can cope with both wet and dry soils.

He says there is nothing new in any of this. "China has a long history of agriculture and 2000 years ago farmers had a pond system to fight against floods. We have a 2000-year history of building terraces that catch water in the rainy season and keep it through the dry season But we forget this.

Locals stroll through a rice paddy in Shenyang designed by landscape architect Kongjian Yu.

Photo: Supplied

"Over the last 40 years, China has urbanised quickly and our cities have been cut off from nature. Industrial technology has been used to drain away storm water and put it into the ocean. But the next month the cities are dry. There's an overall shortage of water in China and the water we have is heavily polluted."

Yu's work specifically addresses the Chinese landscape, bringing back wetlands planted with rice and reintroducing ponds teeming with lotus, water chestnut and fish. But he says addressing environmental problems with productive landscapes and simple technologies has wide application.

"This is not tiny urban gentrification. It is about how messy ecologies and productive, rural landscapes can be urbanised. It's fantastic for how you can solve environmental problems and at the same time produce beauty. For hundreds of years people have distinguished productive landscapes from ornamental ones but now they can come together."