The Wire China:The Sponge Revolution

In October 2013, the coastal Chinese city of Ningbo, which is home to 10 million people and the world’s fourth-largest port, was hit with a torrential food. Wastewater systems and rivers overflowed. Five people were killed, and more than 100,000 houses were inundated with brown food water polluted with sewage, industrial chemicals and heavy metals.

Flooding is a perennial problem in southern and central China, but in the last three decades it has gotten much worse. All along China’s coastline, cities are sprawling, and developers are paving over wetlands and hemming in rivers between concrete walls, leaving no place for floodwater to go. In summer 2020, China surfered 21 large-scale foods — the most in over two decades. More than 30 rivers swelled to their highest levels ever recorded. Authorities had to blow up smaller dams to ease pressure on the gargantuan Tree Gorges Dam astride the Yangtze River, which may have been close to structural failure.

City administrators have responded by laying more pipes and widening canals. But in many cities, like Ningbo, these efforts have been nowhere close to enough.

“Urban food management is a massive challenge in China,” says Faith Chan, an assistant professor of environmental sciences at the University of Nottingham’s campus in Ningbo, China. “The government has studied it carefully and is committed to taking action.” For thousands of years, water and politics have been intimately linked in China. The founder of the mythic first dynasty, the Xia, supposedly left his wife and child for 13 years to construct irrigation canals along the Yellow River, earning himself the appellation “Great Yu Who Controlled the Waters.”

Rescuers evacuate local residents by boat on a flooded road after heavy rains caused by Typhoon Fitow in Ningbo, October 2013. Rapid urbanization and city sprawl have resulted in record-breaking floods over the last decade. Credit: Zhejiang Daily / AP Photo

Rather than build more dams, canals, and floodwalls, China needed to turn its sprawling metropolises into “sponge cities” (haimian chengshi) by clearing vast open areas in low-lying urban centers and filling them with parks and wetlands. In times of plenty, the interlinked green spaces could absorb and retain water. In times of drought, they could filter water and either recycle it for household use or release it gradually into nearby river systems.

Dutch hydraulic engineers, who for centuries devised methods to hold water back, are preparing for climate change with plans to create “room for the river” and to “let the water in. Singapore, Melbourne, and Portland, Oregon, are all, in one sense or another, sponge cities, but Western engineers use clunky terms like “low-impact development,” “sustainable urban drainage system,” and “water sensitive urban design” to describe the designs.

“They all mean essentially the same thing,” says Tim Fletcher of the Waterway Ecosystem Research Group at the University of Melbourne. “But ‘the sponge city’ is a clever marketing term. So, even though the concept is not new, the term captures people’s imagination, including the decision makers and citizens. And that’s really helped it to be successful.”

Indeed, China’s sponge city program is rapidly scaling up. With orders to become sponges by 2030, 70 percent of Chinese cities are scrambling to draw up plans. The initiative’s goals are also growing broader and more ambitious. What began as a targeted intervention to affordably manage urban flooding has now become a central pillar of two epochal policy shifts: China’s decision to “go green” and the National Adaptation Strategy to make China more resilient to climate change.

“China still has a lot to learn, but I think it could leapfrog us in the next decade,” says Nanco Dolman, who works in the Water Resilient Cities group at the Dutch civil engineering firm Royal HaskoningDHV. “In Europe, we do lots of local-scale, low-impact design projects at street or neighborhood level. But China is implementing these projects on the district and city scale, e.g. urban wetlands or eco-corridors. It is showing that ecological design can be about more than just green roofs and rain gardens — it can be a revolutionary rethink of the very texture of a city.”

One of the most well-known is Yu Kongjian, dean of the School of Landscape Architecture at Peking University, who leans into this revolutionary role. Yu likens the modern practice of building cities out of concrete to the ancient Chinese practice of binding women’s feet. Like the radicals and reformists of the May Fourth movement of 1919, who called for a sharp break from the old ways, Yu preaches the need for a “Big Foot Revolution” — to rip of the restraints and let the green space grow.

“We need sponge cities,” says Yu. “We need to adapt to nature, to adapt to stormwater. We need to remove the concrete and recharge the aquifers. Otherwise, we’re doomed. We’re going to die. Sponge cities are not just a philosophy. They’re an action.”

PERSUADING THE PARTY

Yu is not the only major Chinese designer or theorist of sponge cities, but he is the program’s most famous and influential advocate. As a graduate student and junior academic in the 2000s, he laid essential intellectual groundwork for the program by persuading the Chinese government that “ecosystem-based services” could save China from environmental collapse.

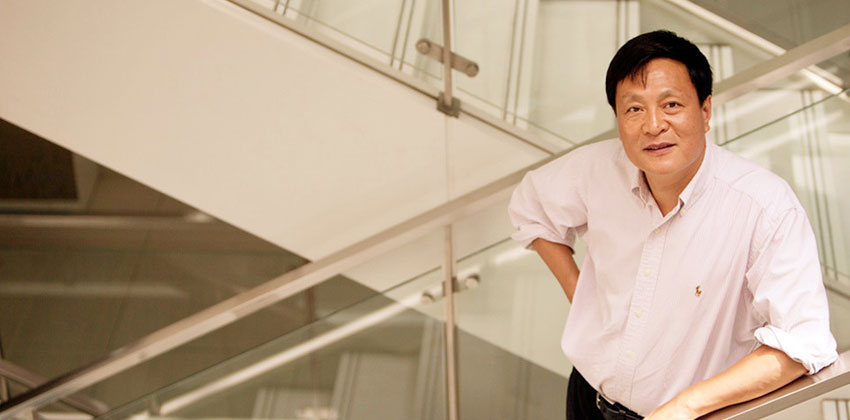

Yu Kongjian is one of the principal advocates for sponge cities. Crefit:Turenscape

Charming and fluent in English, Yu also plays an important role in bridging Chinese planners with their Western partners. In Ningbo, for instance, Yu is one of the main designers of New Eastern Town, a sponge city that is being developed piecemeal by various designers and financed largely by public private partnerships. Centered around the newly built Ming Lake, the development contains a business district, cultural facilities, transportation links, residential high-rises, and walking and cycling paths through finger-like terraces planted with reeds, flowers, and trees.

Yu’s Beijing-based design firm, Turenscape, has completed over 500 sponge parks in over 200 cities across China. His vision for the Chinese city, he says, is “agrarian urbanization,” an eco-utopia that involves “grafting contemporary ways of living with 2,000 years of nature-based agricultural life.”

Born in a rural village in Zhejiang province, Yu studied forestry in Beijing before going on to the Harvard Graduate School of Design for his PhD. After graduating, he abandoned a lucrative career designing luxury homes in Los Angeles to take a teaching job at Peking University. He later founded the university’s Graduate School of Landscape Architecture.

While Yu was still in graduate school, he began to publish academic articles about China’s “ecological security,” which, at the time, was out of step ! with the party line. The Communist Party’s position was that climate change was not a security issue, and that China, as a developing country, had a responsibility to prioritize economic growth.

But a group of scholars at Peking University, including Yu and the influential climate change expert Zhang Haibin, began to push back. Environmental degradation imperiled China’s national security and social stability, they argued — not to mention China’s ability to sustain rapid economic growth.

Yu found innovative ways to illustrate his findings, including satellite imagery and geospatial mapping. In 2006, he presented his research to Wen Jiabao, who was then serving as China’s premier. Wen agreed to sponsor a study, and Yu’s report was published in 2009 under the title “National Ecological Security Pattern Plan for China.” It found that China was on the brink of a wide-ranging ecological crisis, including flooding, desertification, erosion, and biodiversity loss — each of which posed its own national security crisis and each of which was made even more acute by climate change.

Most importantly, Yu’s report noted, if China tried to address these problems individually, without recognizing how they were linked, it was doomed to fail. China needed a “comprehensive solution” — an “ecological” one.

“Kongjian is an advocate for trying to use natural processes to mitigate environmental damage,” says Peter Rowe, who teaches at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. “That’s a difficult concept to sell in China.”

Yu, however, turned out to be a good salesman, persuading many Party elites. After decades of unbridled development and minimal limits on pollution, a consensus was emerging that China needed to change course.

The point is not just that the Party aspires to “build a beautiful China,” but also that it is following a distinctly Chinese philosophy of “harmony between man and nature” (tianren heyi).

“For the past 40 years, we have followed a Western model,” says Yu. “We have copied everything from Western urbanization when building infrastructure and imagining urban life. In the process, we have become totally disconnected from our tradition in terms of the way we live and our relationship to nature.”

The solution, he says, is to go back to Chinese “ancient wisdom” and integrate natural systems into human design.

“Kongjian Yu is a master of merging global ideas and applying them in the Chinese vernacular,” says Frederick Steiner, dean of the University of Pennsylvania Stuart

Weitzman School of Design. “He’s extremely important in his ability to understand the broader global trends, but then make them very Chinese.”

While most Chinese intellectuals are extremely risk-averse about writing in English, particularly on political topics, Yu has — so far — proven skilled at threading the political needle. The fact that he feels so free to voice his ideas also shows how comprehensively the Party has embraced them.

Yu Kongjian’s great talent isn’t just his skill as a designer, says Steiner. It’s “his ability to promote his ideas to the power structure.”

THE SPONGE OLYMPICS

Thanks to China’s unmatched capability for central planning and civil engineering, it has taken less than a decade for Yu to start enacting his ecological vision at scale.

“It takes a very long time in the Netherlands to implement our designs and to test and validate new innovations,” says Chris Zevenbergen, a professor of hydraulic engineering at the University of Delft who collaborates with Chinese cities and universities on knowledge transfer projects. “But in China, it is completely different. I spend my summers in Nanjing, collaborating with experts and students. When I come back the next summer, we can already see our designs being implemented.”

Indeed, the astonishing speed of the sponge city rollout illustrates China’s ability to use its cities and provinces as competing laboratories of innovation.The Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development ordered a nationwide pilot trial. By March 2015, less than 18 months later, over 100 cities across China had made a preliminary application to transform themselves, and the Ministry had selected 16 semi-finalists. Each semi-finalist then had three years to build and operate a “sponge city demonstration area” that was at least 15 square kilometers in size — or, more than four times the size of Central Park.

One of the 16 was Pingxiang, a coal-mining city of 1.8 million people in the food-prone hills of western Jiangxi province. With a stagnant economy and decaying water

infrastructure, Pingxiang was used to crippling foods. In Wanlong Bay, a former mudflat north of the city that had been paved over by urban sprawl, local residents often had to use boats to get around during the rainy season. The city government had been trying for years to manage the flooding by laying new drainage pipes and sending teams of earth moving machines to dredge the canals. Nothing worked.

Sanya Mangrove Park in Sanya City, Hainan Province, designed by Kongjian Yu and his team. The park was awarded an Honor Award by the American Society of Landscape Architects. Credit: Kongjian Yu, Turenscape

Pingxiang officials took a gamble by taking part in the program. In October, a few months into the competition, the State Council published a high-level guidance document for the competing cities, outlining the “basic principles” of sponge city construction. These included “adhering to the ecology-based natural cycle, giving full play to mountains, forests, fields and lakes and other original terrain and landforms on the accumulation of rainfall, giving full play to vegetation, soil and other natural substrates on the infiltration of rainwater, giving full play to wetlands, water bodies and other natural purification of water quality, and striving to achieve the natural cycle of urban water bodies.”

In other words, the central government knew what it wanted sponge cities to do (retain water) and the basic principle of how they should work (use ecology-based solutions). But local officials had to figure out the rest — including how to pay for the sponge treatment.

The Ministry had set aside a small pot of 20 billion yuan (about $3 billion), which wasn’t much when divided between the 16 competing cities. The State Council advised local officials to make up the difference by issuing bonds and “encouraging” local banks and investors to contribute. On the biggest question of all — the process of evicting communities and demolishing infrastructure to clear the land for these new “sponge” parks — the State Council was silent.

Pingxiang’s mayor, Li Xiaobao, said that he was actually nervous when he got the news that his city had been selected to compete. He now had just three years to transform his city into a “sponge” while also solving the intransigent challenge of the annual foods — with no meaningful technical guidance or engineering help.

Nevertheless, Pingxiang officials got to work. Upstream, they built diversion tunnels to shunt water around the city rather than through it. Inside the city itself, they built marshes, mudflats, and three lakes as big as the Onassis Reservoir in Central Park, surrounded by parks with terraced green lawns. Downstream, they built pump stations to regulate the

fow out of the system.

It worked — partly. The next two foods that hit Pingxiang were still notable, but they caused much less damage than foods of similar sizes had caused in previous years. When the Ministry announced the results of the pilot competition, Pingxiang had come in first place. Li was celebrated as a hero in national propaganda films and news stories.

Almost immediately, the Ministry decided to take the “sponge city” program national. In phase two, 14 larger cities — including the four “Tier 1” cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Tianjin — were ordered to become sponges, too. By 2020, just five years after Pingxiang started implementing its sponge city program, the central government set a target that 20 percent of cities in China should collect and recycle 80 percent of their rainwater. By 2030, 70 percent of Chinese cities must meet the target.

“GREEN IS NOT ALWAYS GOOD”

This top-down approach to implementation has its critics, of course. After the first pilot program was completed, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development replaced its vague guidelines with an exhaustive set of technical standards, drawing largely on the best practices from Pingxiang. Now, city offcials and their design partners across China often have the opposite problem: lacking the ability to adapt the program to their local needs.

“They are building sponge cities according to rigid rules and strict design standards — rationally, like a grid,” says Dolman, of Royal HaskoningDHV. “We have standards in the Netherlands, of course, but they are more generic. You have to leave room to have a dialogue or discussion and fnd more tailored and community attuned solutions.”

Others fear that China’s bureaucratic culture is overconfident about its ability to engineer its way out of climate change, which is a complex challenge requiring more than just a one-dimensional solution.

“Chinese bureaucrats — especially in the field of urban planning — like to think of the world as a scale model,” says Li Yifei, professor of sociology at NYU Shanghai. “They see extreme weather events as aberrations, or external shocks to that model, that can be accounted for and canceled out, as if any problem in the world could be engineered away.”

In reality, the threat is that climate change creates unforeseen risks or compounding problems that are hard or even impossible to plan for. Most provinces’ five-year plans lack clear references to urban climate change adaptation, which suggests that China is doing relatively little comprehensive climate planning on the local level.

Moreover, given the top-down mandate regarding “green” initiatives, the local incentives can become distorted. Many local offcials, for instance, are trying to double- or triple count the credits that they can get from any given sponge drainage project, according to Li.

“For example, they send their project to the National Development Reform Commission to get recognition as a ‘low-carbon city.’ Ten they might pitch the same project to the Ministry of Science and Technology as a ‘smart city’ project. And they might repackage it as an energy-efficient housing project and market it to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development for some other recognition,” Li notes.

As they try to game the system — extracting maximum political benefits and subsidies with minimum investment — China’s sponge cities may end up compromising on, or even ignoring, the technical specifications that make constructed wetlands effective at absorbing and cleaning floodwater.

And if this is the case, it will be difficult for anyone — Chinese or foreign — to know. Experts say the monitoring systems that are necessary to keep the wetlands healthy are another likely weak spot in China’s sponge city program.

“China still has to figure out what data to collect, and how to collect it,” says Frans van de Ven, associate professor of Urban Water Management at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. “You can imagine that this new way of thinking asks for new data to be available. Recording rainwater is simple enough, but when it comes to, say, the ecological conditions of the water system, sometimes that is monitored and sometimes it is not.”

There is also an asymmetry between Chinese cities’ voracious interest in acquiring knowledge from Western urban planners, and their reluctance to share their own data in return.

“China offers very little information about what it is learning from its own projects — bad and best practices, and so forth — back to EU collaborators,” says the University of Delft’s Zevenbergen. “The pilot projects started in 2014 have been evaluated, but the results have still not been shared [with China’s European technical advisors]. Tis is constraining the collaboration with the EU, because, for some reason, it’s seen in China as a politically sensitive issue.”

Finally, some have argued that the new Chinese concept of “ecological civilization” differs from Western ideas of environmental conservation in subtle but important ways. In a recent critique, Allan Shearer, the Associate Dean of Research & Technology at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture, argued that this implies China’s goal is to prevent systemic environmental collapse not for its own sake, but because it would create problems for human beings. In other words, as long as the ecological system “works,” individual elements near collapse, such as endangered species, can be safely ignored.

“Green’ is not always good,” says Liu Junyan, senior campaigner for energy and climate at Greenpeace East Asia. “You have to emphasize that the biodiversity and the diversity of the ecosystem is most important for maintaining the basic function of nature.” Liu notes the sponge city program is well-intended but poorly — and often destructively — executed.

Frederick Steiner, at the University of Pennsylvania, believes these criticisms are unfair. “Think about Central Park,” he says. “It isn’t just some pristine place that was preserved — a fragment of Manhattan that survived urbanization. It was designed. People were relocated. Its construction was part of New York’s urbanization process. Many people do not see landscapes as infrastructure, like bridges or roads. But they are.”

Like traditional infrastructure projects, sponge city projects face serious challenges to execution. Since they require massive funding, construction time, and the political difficulty of acquiring the land, Western countries seem unlikely to copy China’s national level policy of sponge-ification anytime soon. Democratic countries also require consensus among the stakeholders, which can be an obstacle to radical change.

“Imagine telling New York City residents that they’re going to be drinking recycled sewage,” says Harvard’s Rowe. “That’d be a hell of an ask.”

So far, the West is also missing the ideological spin that has made China’s national sponge city program such a success. In China, it is about much more than urban water management, climate change adaptation, or even the greening of China’s cities. It is a patriotic program to foster a distinctly Chinese philosophy of ecology — one that centers around the relationship between humankind and nature.

“Every year that I go back, I see the scope of the sponge city concept broadening inside China,” says the University of Delft’s Zevenbergen. “It’s no longer just about water quality. It’s about livability. It’s about local benefits. It’s about sustainability.”

Kongjian Yu's book. Credit: Terreform

Despite the lack, so far, of a similar uptake in the West, however, many landscape architects and hydraulic engineers think that China’s large-scale adoption of sponge cities has consequences for the rest of the world. It may even cause positive ripple effects.

“I have noticed, throughout my career, that the ‘rise’ of ‘new’ countries in championing low-impact development seems to re-energize the countries that have been doing it for a while,” says Fletcher, of the University of Melbourne. “China’s embrace of the sponge city concept, and their effective communication of it, has encouraged other countries to champion the same principles.”

That seems to be part of Yu’s vision as well.

“I have no separation between Eastern and Western,” he says. “To me, there are just two kinds of civilization right now: one civilization means industrialization, and one civilization means ecological civilization. Western and Chinese ideas are just at different stages right now, but we will eventually come together to seek ecological civilization.”

Source: https://www.thewirechina.com/2021/07/18/the-sponge-revolution/