THE NEW YORKER: The Future of Public Parks

Central Park is considered by some to be Frederick Law Olmsted’s crowning achievement. Photograph by Matthew Pillsbury

The landscape architect Sara Zewde met me at the corner of Malcolm X Boulevard and Central Park North, a busy intersection that overlooks both the Harlem Meer and a Dunkin’ Donuts, the park and the city. Her home and her office are nearby, but there’s a deeper meaning in this location for Zewde, who is one of a small number of Black women licensed in landscape architecture in the United States. Glancing at Central Park, which is considered the crowning achievement of Frederick Law Olmsted (and his collaborator Calvert Vaux), Zewde told me how Olmsted’s writing had been “formational” for Malcolm X during his time in prison, when the civil-rights leader was searching, as he later recounted, for texts that spoke “the truth about the black man’s role.” He found part of that truth in Olmsted’s account of his travels through the South before the Civil War, collected in “The Cotton Kingdom.” “Books like the one by Frederick Olmstead,” Malcolm X said, “opened my eyes to the horrors suffered when the slave was landed in the United States.”

In 2019, Zewde, a native of the South,

embarked on a four-month-long project retracing Olmsted’s journey from D.C. to

Louisiana. She regards Olmsted’s Southern travels and, indeed, his way with

words, as a core yet understudied aspect of his career. “Obviously, Olmsted

could not have seen the future and his influence on Malcolm X, but I reflect on

this intersection a lot,” Zewde said. “Olmsted did talk about the value of

Black people gathering,” she continued. “He didn’t foresee Harlem becoming the

mecca that it is for the global Black diaspora, but here we are.”

On the occasion of Frederick Law Olmsted’s

two-hundredth birthday, Zewde is part of a generation of landscape architects

wrestling with his end-of-day shadow. Olmsted espoused abolitionist views, but

his projects displaced Black and Native communities. He was a democrat who

modelled America’s public parks on aristocratic estates, and a nature lover who

moved mountains of dirt to reshape topography for aesthetic purposes. To the

general public, he is a venerated name, most often recalled during strolls

through his parks in New York City, Boston, Chicago, Hartford, and Montreal

that bring the forest to the city and the city to the forest. Contemporary

landscape architects invoke Olmsted to help convince planners and politicians

that parks are worth the investment, but Olmsted’s style and his politics don’t

necessarily address the needs of 2022. Landscape architects want to present

themselves as the designers who are most able to combat climate change and

reduce spatial inequalities, and, for those ideals, they are looking beyond

Olmsted.

“He was wildly unsuccessful at everything

except his writing and his landscape-architecture career, which came later in

his life,” Billy Fleming, a professor in the Weitzman School of Design at Penn,

told me. Olmsted was the child of an affluent Hartford merchant, and he tried

farming and journalism before settling on construction and park planning.

Popularizing the term “landscape architecture” (which Olmsted did) and

transforming the discipline into a licensed Ivy League pursuit (as his son did)

cut off its history and its practitioners from the millennia of expertise

acquired by humans working on the land. Fleming prefers to teach a longer

history of landscape architecture that includes Indigenous communities and the

ways in which they continue to design the land, as well as radical groups like

Britain’s Diggers, who used gardening as a way of taking back public space and

building political power.

Kian Goh, an assistant professor of urban

planning at U.C.L.A., said she uses Olmsted as an example of the lineage of

urban parks—but one for which students swiftly see the limits. “Yes, you have

idealistic ideas of full access, but, really, parks like Central Park and

others have become centers of real-estate speculation in the city,” and the

recent critiques of both the High Line and Little Island on Manhattan’s West

Side bear this out. “This is where I find the most purchase among students,”

Goh said: “the idea that green space has a history of exclusion, even though

the original ideals might have been different. They don’t think that the ideas

of folks like Olmsted stand the test of racial and social-justice critique now.

How do we decolonize ideas for public parks?”

Parks like Little Island, in Manhattan, have raised questions about green-space design and inequality.Photograph by Gary Hershorn / Getty

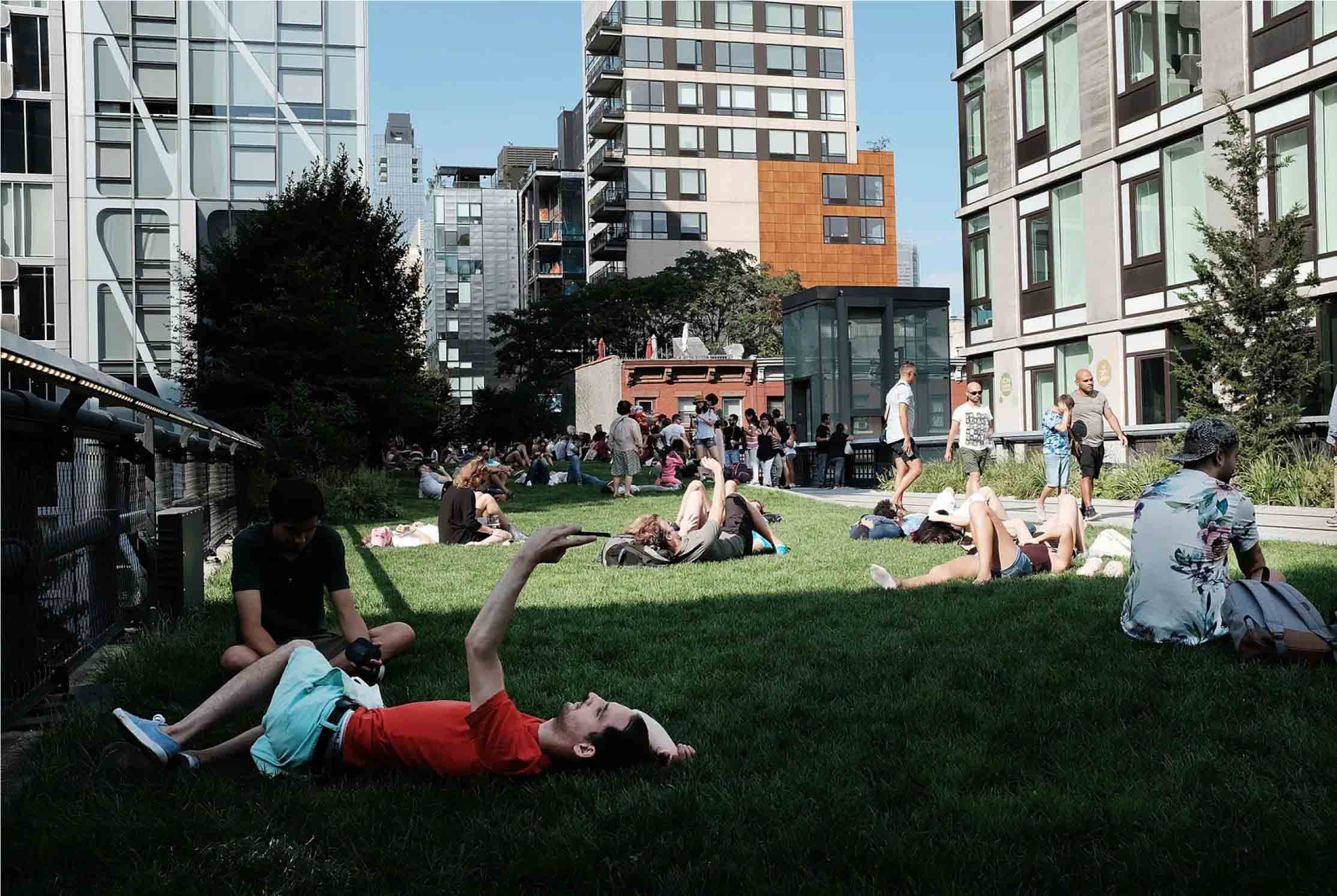

The High Line, in Manhattan, has been critiqued for its role in real-estate speculation.Photograph by Spencer Platt / Getty

Kian Goh, an assistant professor of urban

planning at U.C.L.A., said she uses Olmsted as an example of the lineage of

urban parks—but one for which students swiftly see the limits. “Yes, you have

idealistic ideas of full access, but, really, parks like Central Park and

others have become centers of real-estate speculation in the city,” and the

recent critiques of both the High Line and Little Island on Manhattan’s West

Side bear this out. “This is where I find the most purchase among students,”

Goh said: “the idea that green space has a history of exclusion, even though

the original ideals might have been different. They don’t think that the ideas

of folks like Olmsted stand the test of racial and social-justice critique now.

How do we decolonize ideas for public parks?”

The Emerald Necklace Conservancy, which has

a robust schedule of two-hundredth-birthday plans, has made community the

centerpiece of its programming. In the run-up to this year, staff members and

consultants have held meetings in the neighborhoods surrounding the park,

compensated community members for their time (rather than just the

“professionals” at the front of the room) and emphasized the idea, articulated

by Olmsted in an 1870 speech, that “it does men good to come together in this

way in pure air and under the light of heaven” in parks, and that such

gathering “must have an influence directly counteractive to that of the

ordinary hard, hustling working hours of town life.” In 2022, some of this work

is very mundane: How easy is it to get a permit for a party? Hire a food truck?

Access a bathroom?

Focussing on the communities around parks

is another way to decenter Olmsted: even in places where he originally designed

the park, he hasn’t been the one maintaining it for the past hundred and

twenty-plus years. “The history of these places didn’t start and stop with this

man,” Gina Ford, who worked on a master plan for Hartford parks, including

Keney Park, which Olmsted’s successors designed in his native city, told me.

“These places that were designed by him have oftentimes been at risk and have

been saved by and reclaimed by communities of color.” At Keney Park, the

carriageway conceived by Olmsted’s firm for open-air clip-clopping is now a

popular spot for another kind of public display. “The carriage drive is where

people bring their cars and open up the doors and play really loud music,” Ford

said. “The best landscapes adapt and evolve.”

The Emerald Necklace connects a chain of parks of every personality.Photograph by Marcus Baker / Alamy

Back at the Harlem Meer with Zewde, I asked

her if she uses Olmsted in her professional practice. She thought for a minute

and then brought up a current project to design a one-and-a-half-acre park on

the site of the Kingsboro Psychiatric Center campus in Brooklyn. The assumption

was that the street grid would go through the site and cut it up into lots of

little programmed bits. Olmsted and Vaux, famously, insisted on sinking the

transverse roads through Central Park, and asserted the importance of passive

recreation—of strolling as a civilizing influence. “You go to parks in the hood

and it is basketball courts every square inch,” she says. “Implicit and

explicit is a sense of control. People don’t have a place to just be, to just

hang out—that is something that there is a dearth of and it is something that

we are fighting for in a lot of our projects.”

Despite her intellectual closeness to

Olmsted, and her belief in the ongoing importance of passive recreation, when

she’s looking for an example of a park that allows people to just be, her model

is Walter Hood and his 1999 redesign of Lafayette Square in Oakland. “The

tradition of squares also comes from Europe, usually centered on some sort of

axis or monument or destination. Walter instead designs for people in the

middle. He studied the social patterns of the park before his design: that’s

where they hung out before, that’s where they hang out now.” Coming out of the

pandemic, when urban spaces of all descriptions have proved their worth yet

again, Zewde weighs the understanding of the park as “a place you can engage

with people outside of ownership of each other, or outside of labor and

capital” with the labor required to maintain an Olmsted landscape. As we stroll,

Lasker Rink, on the west side of the Meer, is fenced off and under construction

as part of a project to make the location more accessible and more responsive

to twenty-first-century recreation needs. It doesn’t pay to be too precious

with your heroes: the landscapes of the future can acknowledge the beauty of

Olmsted’s vision while also celebrating the work that it takes to keep a city,

and its citizens, healthy in 2022.