ASLA LAM: The Sponge Evangelist

An old industrial site in 2020, before the construction of Benjakitti Forest Park in Bangkok. Photo © Turenscape, courtesy the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

In awarding the second biennial Oberlander Prize to the Chinese landscape architect Kongjian Yu, FASLA, the Cultural Landscape Foundation and its 2023 jury sent an unmistakable signal about the future of the field. For the prize, which seeks to function as a counterpart to architecture’s Pritzker Prize, Yu is a resonant international figure whose theory of sponge cities saw its influence and exposure steadily grow in the past decade. Gray infrastructure and channelized rivers of the past century are being increasingly daylit and replaced with naturalized environments that absorb water and restore wildlife habitats. Given the accelerating climate crisis and its impact on hydrological cycles, Yu now talks about the need for a “sponge planet,” updated to reflect the urgency of climate adaptation facing human settlements worldwide.

The Oberlander’s inaugural laureate, Julie Bargmann (see “The Stranger Territory,” LAM, December 2021), highlighted landscape architecture’s concern for the quality of soil that life depends on with her focus on reclamation of land degraded by industrial production. Yu’s focus, by contrast, is on the crucial role of water for survival.

But for those familiar with his work and personal story, Yu is more than a theorist of a popular idea. He’s an extraordinary educator who founded China’s first landscape architecture program at Peking University in 1997, graduating hundreds of master’s and doctoral degree students who have gone on to teach, practice, and influence design, development, and policy throughout China and the world.

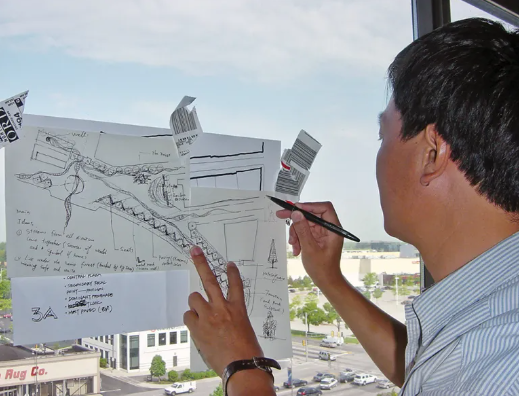

Kongjian Yu, FASLA, sketches the concept for Chinatown Park in Boston in 2003. Photo © Turenscape, courtesy the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

As a child, Yu grew up on a farm and witnessed the cyclical flow of water through the landscape, the recycling of nutrients in crops, and the resurgence of fish stocks during monsoon seasons. Between 1992 and 1995, he completed a design doctorate at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, studying with Carl Steinitz, Honorary ASLA; Richard T. T. Forman; and Stephen Ervin, FASLA, among others. At Harvard, he supplemented his intuitive sense of how nature functioned in the context of traditional farming methods with technical research on ecological design and planning.

Returning to a rapidly urbanizing China in the late 1990s was a shock, he says. His village had been destroyed, paved over with concrete. “When I returned in 1997, I saw that all Chinese cities developed by laying out a grid system of gray infrastructure that copies the American and Western model,” he says. “Rivers channelized, fishponds filled, concrete paving of well lines: the natural infrastructure disappeared. There was a whole vacuum in China of how to deal with urbanism. In 2002, I proposed a nature-based ecological approach to planning: ecology first. Planning must be on ecological thinking as opposed to population projections.”

Turenscape’s 2007 Chinatown Park combined plantings and performance space as part of Boston’s Big Dig infrastructure plan. Photo © Turenscape, courtesy the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

As the founder of Beijing-based Turenscape, China’s first non-state-run landscape office, he set out to fill the vacuum, becoming an expansive and innovative practitioner. Turenscape has since realized more than 300 ecological cities and more than 1,000 projects, bringing a combination of sensitivity to the lifeways of local communities, human-scale contemporary design, and an understanding of the ecological services that natural environments can provide to civic developments and urban infrastructure.

“With my education on ecological thinking at Harvard and own experience in the farm, I came up with the idea how to combine contemporary technology with traditional irrigation systems,” he says. “A modern science of landscape ecology and contemporary design with traditional knowledge about farming and upgraded techniques to solve today’s problems.”

Yet Yu’s importance to China and the world goes beyond his role as a theorist, educator, and practitioner. In the late 1990s, Yu began writing letters to local city leaders and national decision-makers and lecturing across the country, calling on policymakers to restore damaged wetlands and protect habitats for the public interest as well as valuable places of cultural heritage. Protection of wetlands and ecological design became a key national policy priority, eventually promoted by a slogan adopted by President Xi Jinping: “Green water and green mountains are golden mountains and silver mountains.” It was taken to symbolize the state’s official adoption of ecological thinking.

In Sanya Mangrove Park on China’s Hainan Island, Yu replaced a former landfill with fingerlike channels that draw ocean tides into the park. Photo © Turenscape, courtesy the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Elizabeth K. Meyer, FASLA, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Virginia and the inaugural faculty director of the Morven Sustainability Lab, helped establish the Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize as chair of its advisory committee. She compares Yu to a next-generation Ian McHarg, whose 1969 Design With Nature became a beacon of Western ecological planning. Meyer had taught Yu early in his degree work at Harvard, and in the early 2000s, he invited Meyer to Beijing. The Center for Landscape Architecture and Planning master’s degree program, housed within the geology department, had recently been upgraded to its own Graduate School of Landscape Architecture and relied in its early years on visiting scholars from the United States and Europe.

“I could tell how remarkable his aspirations were in that he had the environmental planning rigor of—I wouldn’t say McHarg, I’d say McHarg 2.0, because theories of ecology had changed radically, and our understanding of how ecosystems work had changed radically,” Meyer says of her impression of Yu at the time. “But he also had the formal skill and capacity to arrange landscapes into extraordinary experiences.”

In the 2023 award, the Oberlander jury recognized Yu as much for the beauty and technical excellence of his body of work as for his intellectual and political influence. In projects going back to 2001, Turenscape reclaimed obsolescent industrial sites from pollution and inserted brightly colored playscapes, sculptures, and pavilions alongside verdant, water-absorbing landscapes.

Completed in 2015, Sanya Mangrove Park weaves public uses with performative landscape engineering. Image © Turenscape, courtesy the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

In Guangdong Province, across the Zhujiang River estuary from Shenzhen, he converted an abandoned dockyard into the Zhongshan Shipyard Park, retaining its vernacular industrial architecture as colorful, functional pavilions and turning the contaminated brownfield site into a water-absorbing, interspecies sponge park. In Red Ribbon Park in Qinhuangdao, Hebei Province, he threaded a ribbonlike bench and boardwalk structure through a narrow park along the Tanghe River, cleaning up dumped waste and preserving its lush native vegetation.

Yu characterizes his design sensibility as a combination of contemporary design and vernacular elements of rural farming culture.

“The focus is about protection of Chinese vernacular culture and very sensitive Chinese ecological systems,” Yu says. “Because for 5,000 years Chinese people have been cultivating the land and creating a landscape which is very subtle, very sensitive to any kind of disturbance. Based on my observation when I went back to China in 1997, I was already informed at that time that the waterways had been destroyed, the wetlands were filled and polluted, and there was heavy pollution.”

Jury chair Elizabeth Mossop, ASLA, had taken an interest in Yu’s work since she participated in a panel to review proposals for the public space of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. Turenscape was eventually selected for that project based on submissions that reinterpreted the rural and working landscape traditions of China, remade into an abstracted large-scale public realm. “It was like nothing I had seen in that space before,” Mossop says.

From then on, she followed his growing body of work harnessing natural processes to create new landscapes of recreation that were also performative, offering ecological services including water management, cleaning up pollution, reusing historical artifacts, and flood management. They took on “a broad range of ecological and cultural operations,” Mossop says, “creating really interesting form and beautiful landscapes and experiences for people, but with a deeper agenda as well.”

Turenscape’s 2010 Shanghai Houtan Park is a mile-long constructed wetland on a former industrial site along the Huangpu River waterfront. Photo © Turenscape, courtesy the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

In the last decade, Turenscape’s work has moved increasingly toward engineering urban wetlands, such as in Shanghai Houtan Park, another reclaimed industrial site along the Huangpu River, completed in 2010. Water cycles through the landscape to control flooding and cleanse pollution, and existing industrial structures are integrated into pedestrian footpaths, roads, and terraces. For Qunli Stormwater Park in 2011, Turenscape realized a sponge city from a dying wetland in a new district of Harbin, Heilongjiang Province. Ponds and mounds composed of native grasses, meadows, and silver birch trees create a dense forest setting, balanced by pathways, elevated walkways, and viewing platforms for area residents. In Hainan Province in 2016, Yu designed a mangrove park out of a former landfill that had been contained by concrete floodwalls, and a wetland park out of another polluted urban site, weaving ponds, rice paddies, greenways, and coastal habitats into an ecological system that retains and cleanses water and recharges the aquifer.

For his part, Yu characterizes his design sensibility as a combination of contemporary design and influences that come from traditional and vernacular elements of rural farming culture. He contrasts this with modernist appeals to the garden tradition that historically served Chinese emperors and high culture.

“This elite high landscape culture has nothing to do with today’s urbanism,” he says. “Because we have to solve the problem I call [a] survival issue. That’s why I call landscape the art of survival. You have to solve the problem of pollution, you have to solve the problem of floods, you have to solve the problem of productivity, security of food, protection of ecology. It [has] nothing to do with Chinese traditional art of design, architecture, or landscape. That art is for emperors, for Chinese high culture, so my farming background gives me a deeper understanding of rural Chinese traditions. That tradition is to deal with the land, adaptation of climate, to make wise use of water, to recycle material and nutrients. Those traditions that always people ignore.”

Hing Hay Park in Seattle, completed in 2018, includes one of Yu’s characteristically bright sculptural features, a red metal gateway inspired by Asian paper cutting and folding traditions. Photo © Miranda Estes, courtesy Turenscape and the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

If global civilization as we know it has a chance, according to Yu, it will require massive interventions using, among other things, large-scale implementation of green infrastructure to support water-absorbing ecologies within human settlements, mitigating flows of stormwater and droughts, and allowing water to naturally cycle through local ecosystems, protecting biodiversity, and enhancing food security.

But Yu admits that he has had less luck working with private developers as opposed to city leaders and government officials, suggesting a challenge to his approach unless there were to be substantial regulatory limits on the private market. “The Chinese developers, not many of them—a few of them—are responsible,” he says. “And most of them I think are irresponsible. I always have tension with developers. That’s why my projects are mostly public projects, civic projects. Very few developers, because they are chasing the market.”

The Oberlander Prize comes with a $100,000 award to support public engagement activities over the course of its two-year cycle, which Yu intends to use to proselytize landscape architecture’s essential role in global climate adaptation. He mentions participating in the recent COP28 climate conference in Dubai. “It has put me out as a speaker for the profession to meet the new global challenge,” he says, “to think about landscape globally as a tool to solve the problem of climate adaptation and mitigation. That’s the number one way that I can make use of the prize: as a global speaker for the profession.”

Stephen Zacks is an advocacy journalist, architecture critic, urbanist, and project organizer based in New York City.

Source:https://landscapearchitecturemagazine.org/2024/02/29/the-sponge-evangelist/