Kohler Magazine: Working with Water

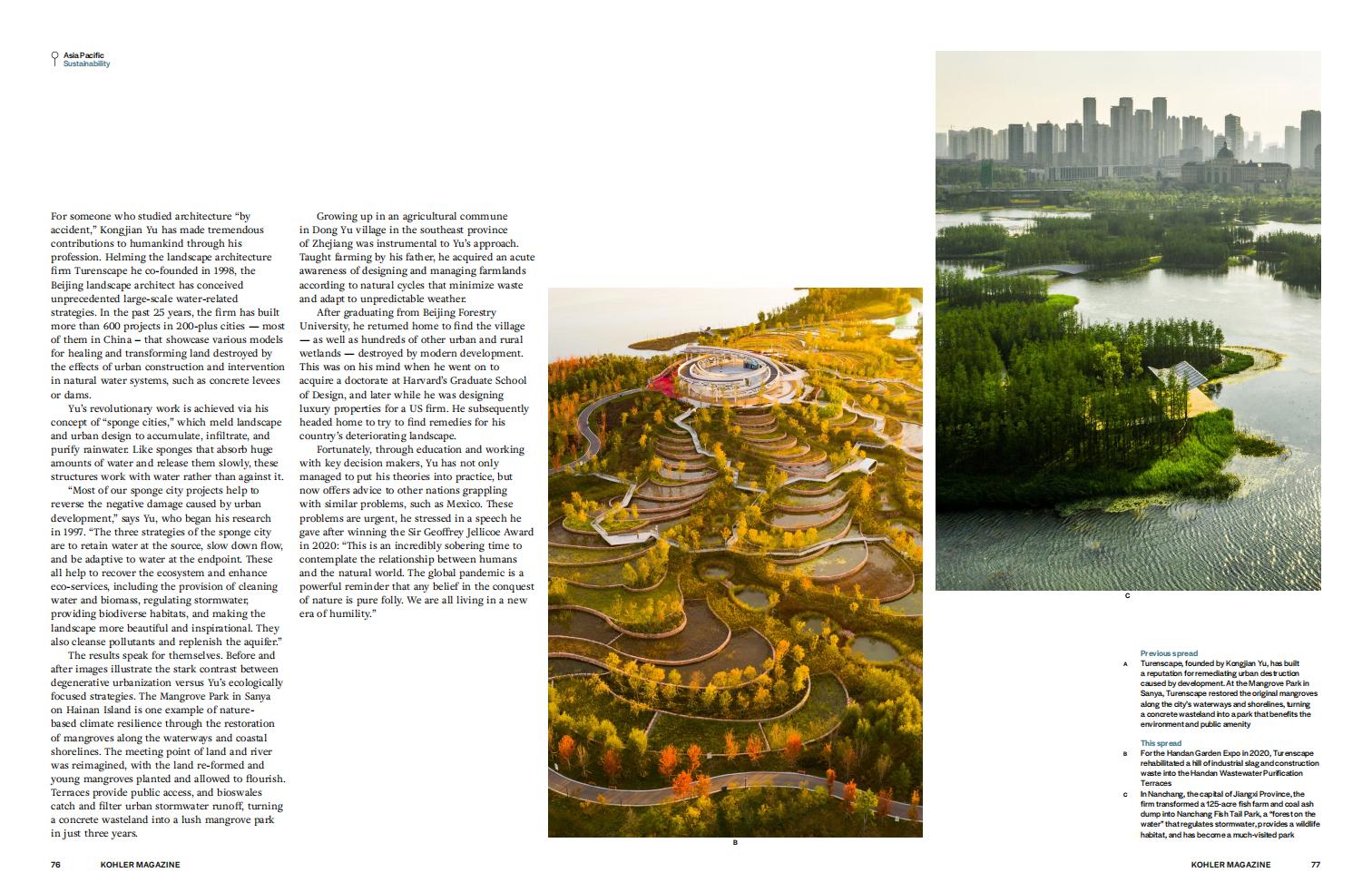

For someone who studied architecture “by accident,” Kongjian Yu has made tremendous contributions to humankind through his profession. Helming the landscape architecture firm Turenscape he co-founded in 1998, the Beijing landscape architect has conceived unprecedented large-scale water-related strategies. In the past 25 years, the firm has built more than 600 projects in 200-plus cities — most of them in China – that showcase various models for healing and transforming land destroyed by the effects of urban construction and intervention in natural water systems, such as concrete levees or dams.

Yu’s revolutionary work is achieved via his concept of “sponge cities,” which meld landscape and urban design to accumulate, infiltrate, and purify rainwater. Like sponges that absorb huge amounts of water and release them slowly, these structures work with water rather than against it.

“Most of our sponge city projects help to reverse the negative damage caused by urban development,” says Yu, who began his research in 1997. “The three strategies of the sponge city are to retain water at the source, slow down flow, and be adaptive to water at the endpoint. These all help to recover the ecosystem and enhance eco-services, including the provision of cleaning water and biomass, regulating stormwater, providing biodiverse habitats, and making the landscape more beautiful and inspirational. They also cleanse pollutants and replenish the aquifer.”

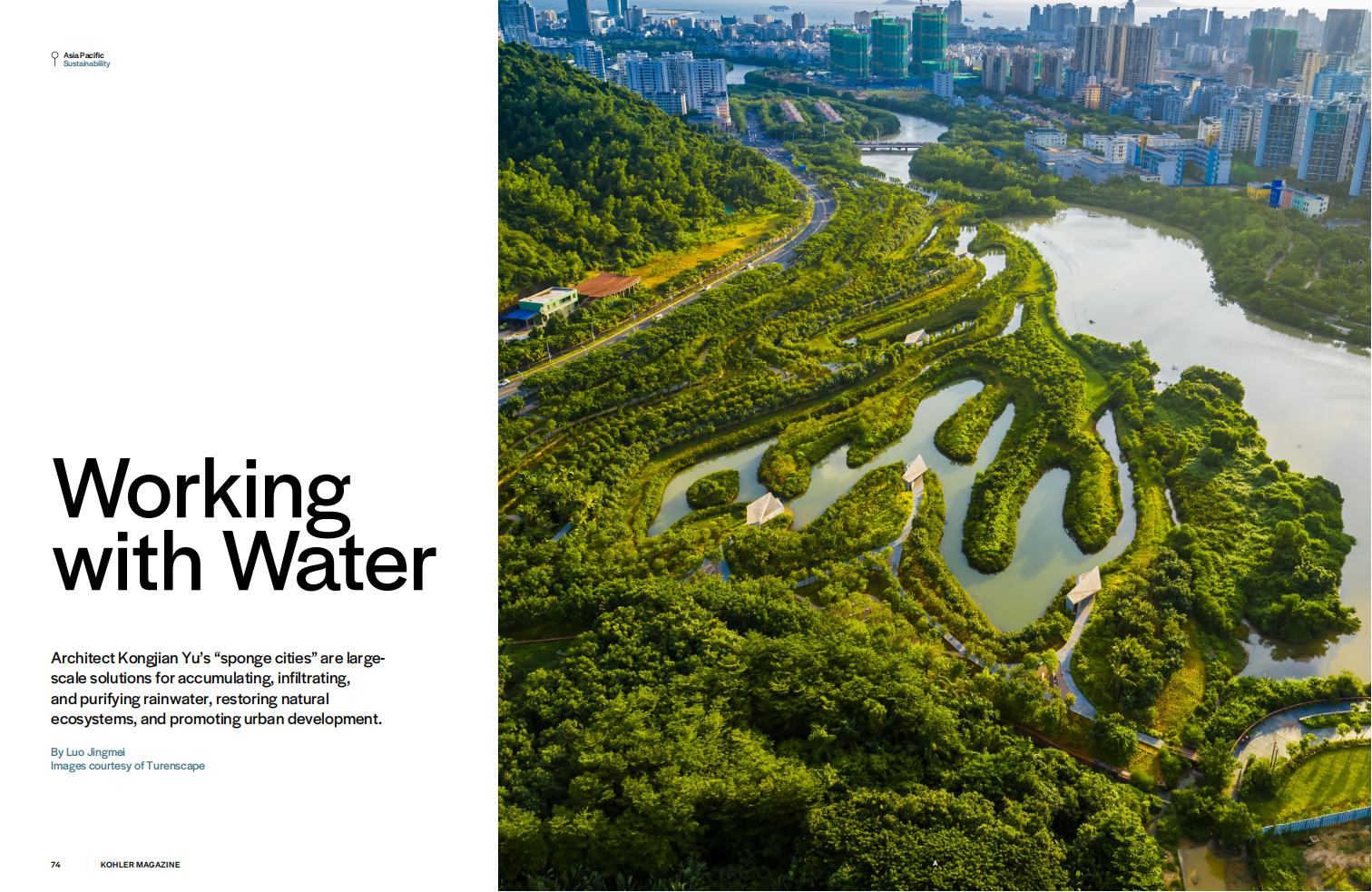

The results speak for themselves. Before and after images illustrate the stark contrast between degenerative urbanization versus Yu’s ecologically focused strategies. The Mangrove Park in Sanya on Hainan Island is one example of nature based climate resilience through the restoration of mangroves along the waterways and coastal shorelines. The meeting point of land and river was reimagined, with the land re-formed and young mangroves planted and allowed to flourish. Terraces provide public access, and bioswales catch and filter urban stormwater runoff, turning a concrete wasteland into a lush mangrove park in just three years.

Growing up in an agricultural commune in Dong Yu village in the southeast province of Zhejiang was instrumental to Yu’s approach. Taught farming by his father, he acquired an acute awareness of designing and managing farmlands according to natural cycles that minimize waste and adapt to unpredictable weather.

After graduating from Beijing Forestry University, he returned home to find the village — as well as hundreds of other urban and rural wetlands — destroyed by modern development.

This was on his mind when he went on to acquire a doctorate at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, and later while he was designing luxury properties for a US firm. He subsequently headed home to try to find remedies for his country’s deteriorating landscape.

Fortunately, through education and working with key decision makers, Yu has not only managed to put his theories into practice, but now offers advice to other nations grappling with similar problems, such as Mexico. These problems are urgent, he stressed in a speech he gave after winning the Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe Award in 2020: “This is an incredibly sobering time to contemplate the relationship between humans and the natural world. The global pandemic is a powerful reminder that any belief in the conquest of nature is pure folly. We are all living in a new era of humility.”