The Architectural Review: City lungs - Benjakitti Park in Bangkok, Thailand by Arsomsilp Community and Environmental Architect with Turenscape

Turenscape and Arsomsilp’s interventions at Benjakitti Park blend landscape, industrial heritage and sports activities in the heart of Bangkok

In 1950, a year after the government took Thailand Tobacco Monopoly (TTM) under its wing to control the kingdom’s cigarette production, a plot of 253 acres of agricultural land owned by the Crown was turned into a gargantuan factory complex. Located in Khlong Toei, in the east of Bangkok and close to the port, lush gardens were replaced by orthogonal streets and modern structures of reinforced concrete. The new industrial buildings churned out billions of cigarettes for a nation of smokers through the decades.

Over the years, Khlong Toei became a high‑density urban area. By the 1980s, Sukhumvit Road, just north of the TTM site, was a major thoroughfare lined with high‑rise condominiums, five‑star hotels and glitzy department stores. To the south, Rama IV Road is also a major street, crossed over by expressways and elevated roads in the perpetual attempt to cope with traffic congestion and overcrowding.

Local consumption of cigarettes also began to decline at the end of the 20th century. In 1991, TTM moved its operation to an industrial estate north of Bangkok, so the owner of the Khlong Toei site, the Treasury Department, embarked upon a major redevelopment project of turning the old cigarette factory compound into a much‑needed urban park.

‘The experience is remarkably different from Bangkok’s fitness centres, usually ensconced deep in the bowels of department stores’

Benjakitti Park, as it was later named, has been developed in several stages. Initially, 51 acres of the factory land was turned into a park, which opened in 1991 as a pilot project. In 2016, after TTM handed over the remaining plots to their owner, the Treasury Department came up with the idea of creating an ‘urban forest’. Although 24 acres of land were converted into a park that year, the ecological and educational ambitions evaporated. Favouring expediency instead, the project was designed and built by the Royal Thai Army. The result was a conventional park with orthogonal geometry.

In 2019, the design competition held for the development of the remaining 178 acres was won by local design company Arsomsilp Community and Environmental Architect in collaboration with Beijing‑based Turenscape. Despite the tight budget and timeline, the compelling masterplan is based on the idea of the ‘sponge city’. Theorised by landscape architect and Turenscape founder Kongjian Yu, the sponge city advocates a primordial return of nature in cities to address and prevent urban flooding in the context of accelerated climate change. At Benjakitti Park, the pre‑existing orthogonal geometry of the sprawling industrial estate was deliberately replaced by biomorphic lines and irregular landforms. An intricate network of reinforced‑concrete walkways on stilts weaves through the park, providing multi‑level circulation and interaction with nature.

In a bid to return the site to its pre‑industrial – and ecologically richer – past, only native species were planted, including Samanea saman or rain tree; Ficus religiosa, also known here as bo tree; as well as banana and papaya trees. Debris from demolished factory buildings was reused to form hillocks and slopes, while a park‑wide hydrological system has been created; rainwater is collected in retention ponds and transferred to new filtering ponds, which helps alleviate flooding and improve water quality in surrounding canals.

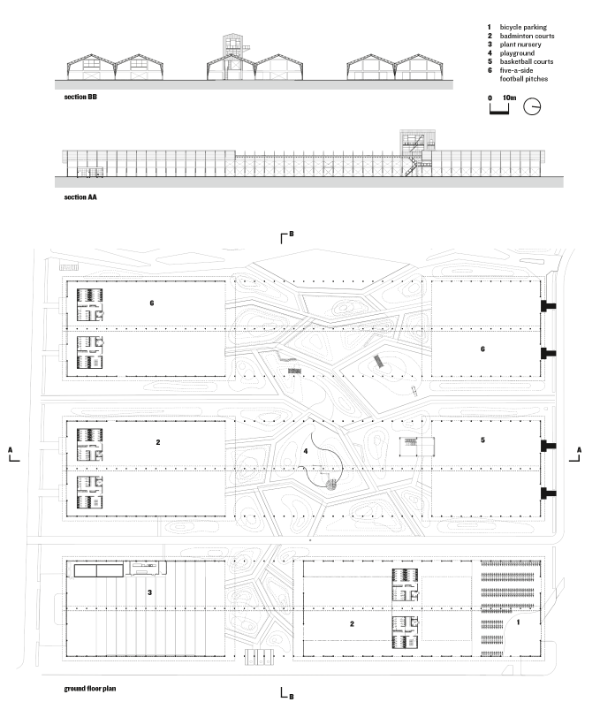

In the north‑western corner of this thriving urban park, three former tobacco warehouses now accommodate indoor sports facilities, skill‑building playgrounds for children and healing gardens for everyone. Arsomsilp and Turenscape’s design cleverly maintains the sense of the site’s industrial past while embracing the possibilities provided by the new park’s ecological design. Separated by narrow alleys, the three tobacco warehouses sit parallel to one another. Each one is a 183m‑long and 37m‑wide one‑storey room wrapped in a reinforced‑concrete skeleton and red brick infill, pierced at only certain points by roller doors and ventilating windows. Each volume is topped with a double gable roof, whose light and minimal steel structure is covered with a corrugated metal roof.

As the site can be accessed from all sides, the architects have broken up the complex further. Stripping sections of the buildings, they have inserted an open garden and playground that splits the three long warehouses into six volumes. The orthogonal circulation has been maintained, overlaid by the new green space, which cuts laterally through the buildings, linking with the main entrances of the park to the north‑west and north‑east. The steel structure of the double gable roofs, however, is preserved throughout – the new space is still partly defined by the old.

The sports centre is run by the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA), adapting and adjusting according to people’s needs. There are six halls – two small ones for futsal and basketball, three mid‑sized ones for ping pong, badminton and a fitness centre, and a large one currently used for pickleball. Each hall is fitted with new flooring, lighting system and metal sheet roof – the old ones had to be replaced. The larger halls also accommodate changing rooms and toilets, as boxes within a box.

The removal of portions of external walls to accommodate different lighting and ventilating needs is particularly remarkable. In the futsal hall, for example, only the concrete columns and beams remain, the brick infill replaced by black nets, while in the badminton hall, the walls are preserved and windows added for ventilation. The result is an architecture for sports that is simple, economical and well connected to the outdoors, but also easily adaptable. According to Chatchanin Sung, project architect at Arsomsilp, ‘the idea is to play sports in a park, so architecture and landscape become one’.

‘The architecture is simple, economical and well connected to the outdoors, but also easily adaptable’

Considering budgetary constraints for both construction and maintenance, the architects have managed to maximise return – in terms of space and flexibility. The high ceilings and wall openings naturally ventilate the sports halls, while the new roofs gather rainwater, which becomes a part of the nature‑based solution for filtering polluted run‑off and providing life support for native species. ‘We want the sports centre to be immersed into the holistic ecosystem of the park, and vice versa,’ adds Chatchanin.

The gabled facades of the old tobacco warehouses are kept on the north and south sides of the compound, but those facing the central playgrounds and healing gardens are totally open, enhancing the sense of openness and opportunity within. Such an intervention is much more difficult to achieve than might first appear. The rehabilitated buildings must meet fire safety requirements as well as universal design guidelines, which are actively promulgated by the BMA. The 70‑year‑old steel roof structure, for example, was cleaned up and coated with transparent rust‑proof coating, while the electrical and fire‑prevention systems must be unobtrusive yet functional.

The doorless sports halls are open daily from 5am to 9pm, just like the rest of Benjakitti Park; sporting equipment is collected at the end of the day by BMA staff and stored away. Mosquitoes abound in the evening, but that is part of the experience of playing sports outdoors here – which is remarkably different from the heavily controlled environments of Bangkok’s fitness centres, usually ensconced deep in the bowels of air‑conditioned department stores. The park’s self‑sustaining ecosystem now also includes herons, storks, snakes, monitor lizards and dragonflies – which can eat more than 100 mosquitoes a day.

At the centre of the compound stands a five‑storey observation steel tower. A remnant of the old tobacco industry’s past, the tower pierces through the factory’s skeletal roof structure. Climbing up the new steel staircase, visitors are rewarded with a panoramic view of the city’s latest and much‑loved public park. Surrounded by the glittering high‑rise towers of central Bangkok, I feel hopeful. This oasis enables the coexistence of people and nature in the tropical, modern city.

It might be a little rough around the edges, but the sports centre sets the scene for new stories to be written. The former factory’s own team, the Thailand Tobacco Monopoly Football Club, dissolved in 2015. Today, the buildings and their grounds are not restricted to workers, but instead welcome the ever‑changing demographics of contemporary Bangkok – and will no doubt continue to evolve over the years.