Shenyang Architectural University Campus

Project Information

- Project Location:

- China Shenyang, Liaoning

- Project Scale:

- 21 Hectares

- Design Time:

- January 2003

- Build Time:

- 2004

- Client:

- Shenyang Architectural University

- Award List:

- 2005 ASLA Honor Awards

- Related Papers

Project Profile

1. Project Statement

This project demonstrates how agricultural landscape can become part of the urbanized environment and how cultural identity can be created through an ordinary productive landscape. The overwhelming urbanization of China is encroaching upon much arable land. With a population of 1.3 billion people and limited tillable land, food production and sustainable land use is a survival issue that landscape architects must address.

2. Objective and Challenge

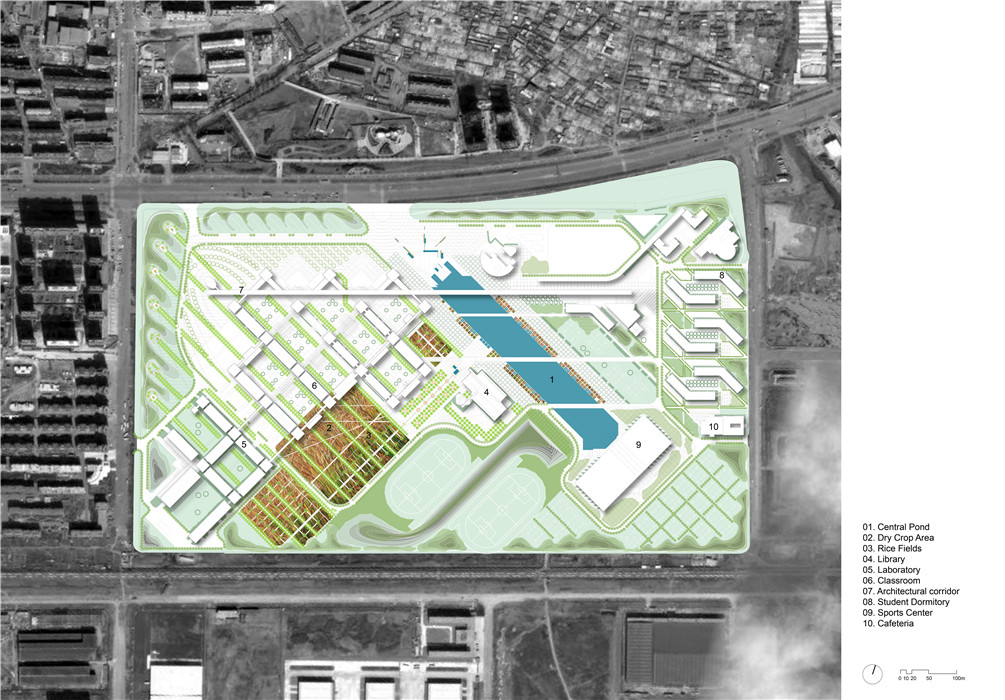

In March of 2002, the Shenyang City in North China’s Liaoning Province commissioned the designer to create a new, 80 hectares suburban campus for Shenyang Architectural University. Originally located downtown, the university was established in 1948 and played an important role in educating architects and civil engineers for the city of Shengyang and for the country as well. But due to a recent dramatic national surge in interest for architecture in China, the enrollment of the school ballooned, creating congestion and overcrowding in its downtown, urban location. After much deliberation, the school decided the best solution was to move the entire campus to the suburbs. The project submitted here is one portion of the campus at the southwest side of the campus, with an area of 3 hectares.

The design had to contend with the following existing site conditions and budgetary limitations:

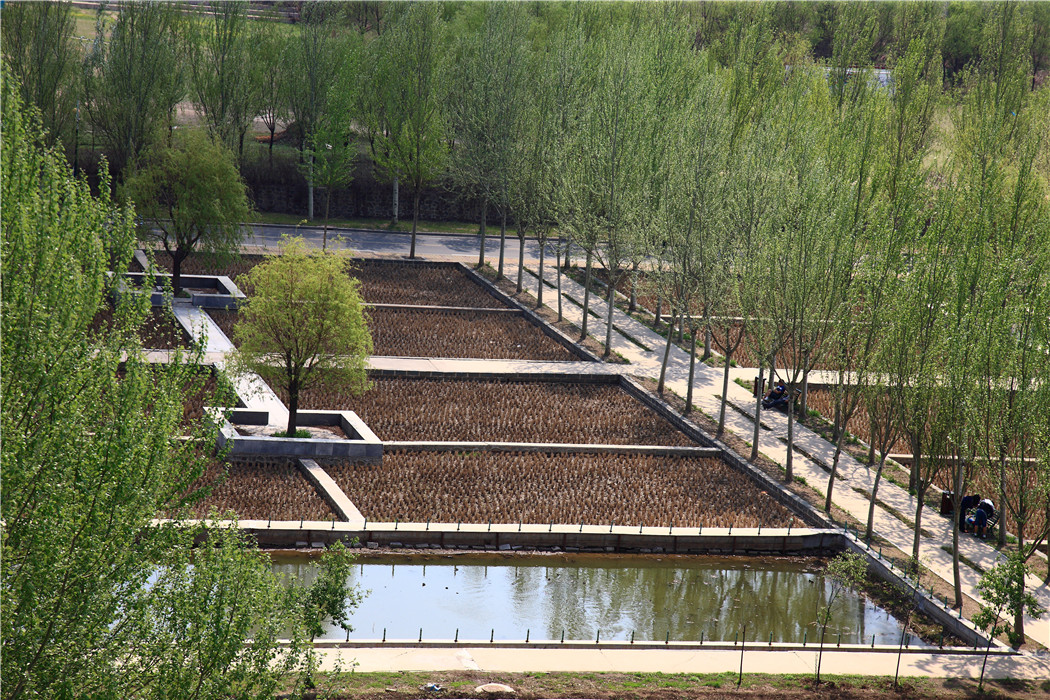

(1) Former agricultural use: the new site for the proposed campus was originally a rice field, the origin of the famous “Northeast Rice,” known for high quality due to cool climate and its longer growing season than the those from the southern China (one single crop of rice in this area will last from the mid May till the end of October, while in south China it can only last 100 days, this is one reason that rice can be used as a landscaping material). The soil quality was good and a viable agricultural irrigation system was still in place.

(2) Small budget: only about one US dollars per square meter was allocated for landscaping. Most of the budget funded the design and construction of 320,000 sq m of new university buildings.

(3) Short timeline: the university required the design to be developed and implemented within one year. Classes were expected to begin in the fall semester of 2003.

3. Design Strategy

Landscape architects working in China must address issues of food production and sustainable land use, two of the biggest current issues on China’s horizon as the country moves towards modernization. The overwhelming urbanization process in China is inevitably encroaching upon a large portion of China’s arable lands. With a population of 1.3 billion people, but with only 18% arable land, China is in danger of using up one of its very valuable and limited resources.

The concept of this design seeks to use rice, native plants and crops to keep the landscape productive while also fulfilling its new role as an environment for learning.

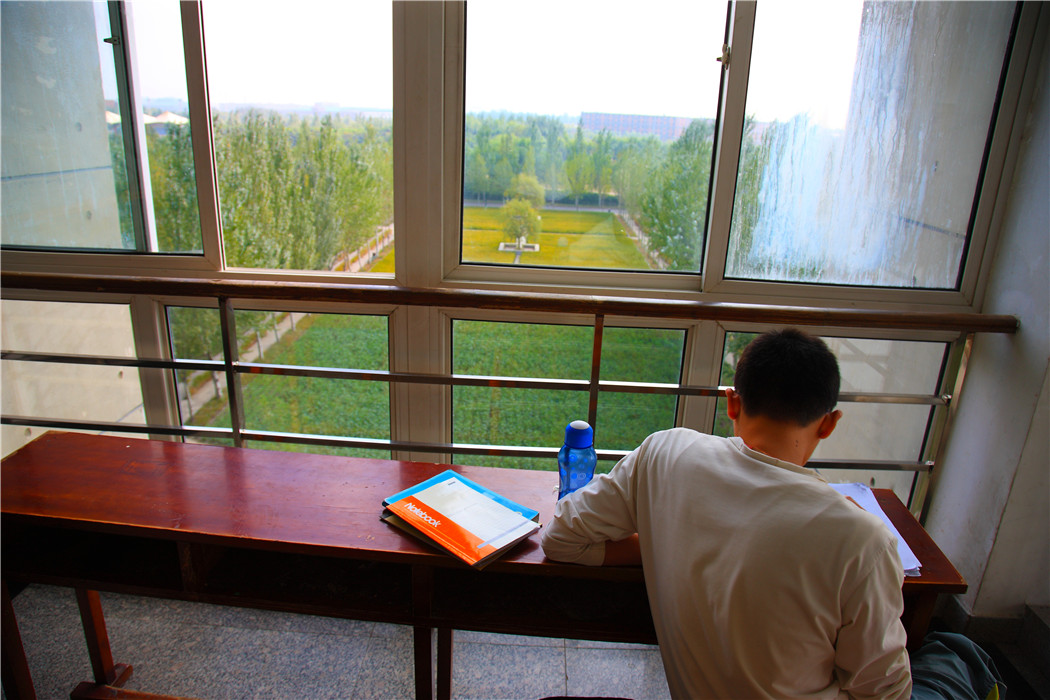

It is designed to raise awareness of land and farming amongst college students who are leaving the land to become city dwellers. In addition, the designer also seeks to demonstrate how inexpensive and productive agricultural landscape can become, through careful design and management, usable space as well.

4. Conclusion

(1) The productive campus rice paddy: not only designed to be a campus with small open platforms, spanning the landscape, the campus is also a completely functional rice paddy, complete with its own system of irrigation.

(2) Other native crops, such as buckwheat grow in rotation across the campus, annually. Native plants line pathways.

(3) The productive aspect of the landscape draws both students and faculty into the dialogue of sustainable development and food production. By situating a new architecture school within a functioning rice paddy, the design allows the process of agriculture to become transparent and accessible to all on campus. Management and student participation become part of the productive landscape. The farming processes can potentially become a laboratory for students and the faculty as well.

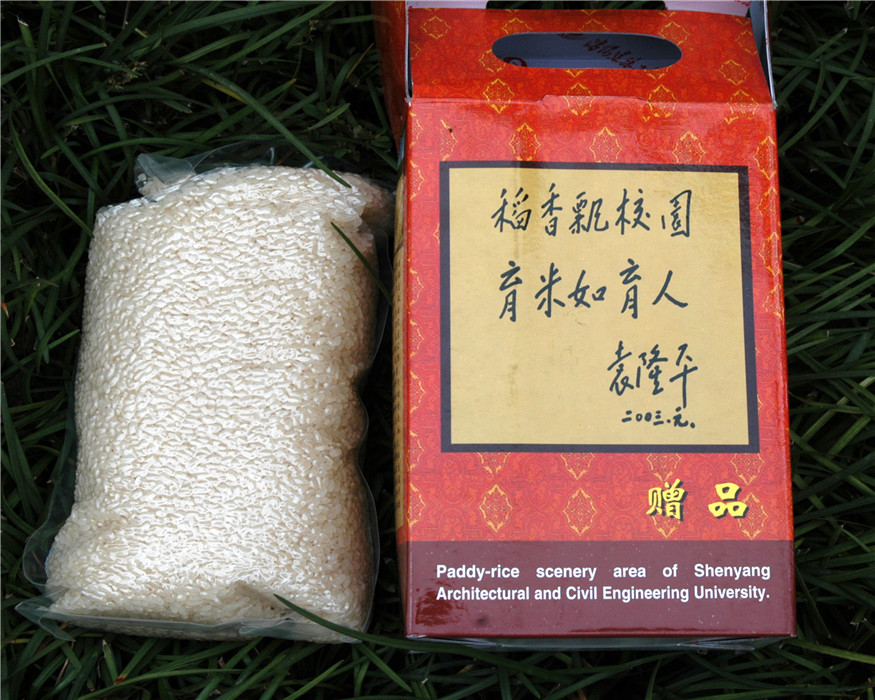

(4) Golden Rice became an university icon: the rice produced on the campus is harvested and distributed as “Golden Rice,” serving both as a keepsake for visitors of the school, and also as a source of identity for the newly established, suburban campus. But perhaps most importantly of all, the widespread distribution of “Golden Rice” could raise awareness of new hybrid landscape solutions that could both continue old, yet crucial uses such as food production, while supporting new uses, such as the education of China’s new architects.