Benjakitti Forest Park

Project Information

- Project Location:

- Thailand Bangkok

- Project Scale:

- 42.3 Hectares

- Design Time:

- December 2019

- Build Time:

- March 2022

- Client:

- Finance Ministry of Bangkok, Thailand

- Award List:

- 2025 World Green Design Awards,2024 IFLA AAPME Awards,2024 UIA 2030 Awards, 2024 AZ Landscape Architecture Awards, 2023 WAF Landscape of the Year,2023 UIA Friendly and Inclusive Spaces Awards

- Partners:

- Arsomsilp Landscape Studio

- Related Papers

Project Profile

1. Project Statement

In the bustling urban heart of Bangkok, our team has transformed the site of a former tobacco factory into a low-maintenance regenerative system that intercepts and reduces the destructive force of storm water, filters contaminated water and provides much-needed wildlife habitat. In addition, Benjakitti Forest Park now provides the largest public recreational space for residents of downtown Bangkok and its environs, and has become a new cultural symbol for the world-renowned vibrancy of Thailand’s capital city. The project, completed at low cost on a compressed timeframe of just 18 months, offers a replicable modular approach to urban engineering that can transform lifeless, concrete-paved ground into a resilient living ecosystem that provides a full range of ecosystem services.

2. Objective and Challenge

Located in the Chao Phraya River Delta, Bangkok is a densely populated city with more than 10.5 million residents. The urban area is flat and low-lying, with an average elevation of just 1.5 metres (4 ft. 11 in.) or less. Most of the area was originally swampland, which was gradually drained with canals and extensive groundwater pumping and irrigated for agriculture. The region experiences a monsoon climate with an average precipitation of about 1500 mm (59 in) per year. Extensive groundwater pumping has caused severe subsidence; that, coupled with the effects of global warming, has resulted in increased flood risk due to Bangkok’s low elevation and inadequate drainage infrastructure. Heavy downpours cause urban runoff to overwhelming the drainage systems, which in turn leads to severe flooding that affects much of the city.

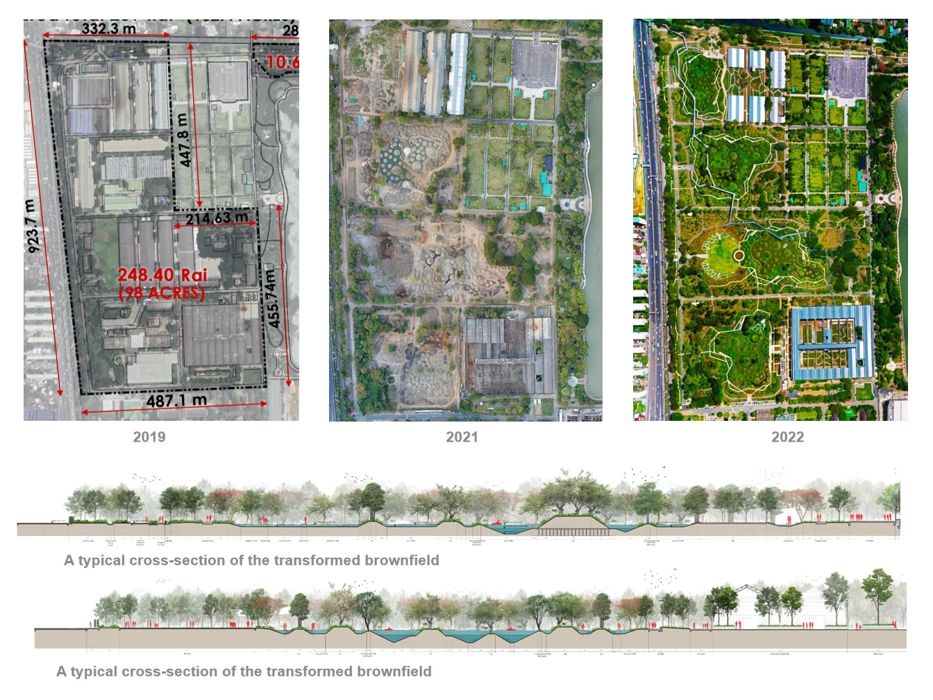

The project is located in central Bangkok’s Khonti District, with an area of about 102 acres. The site was formerly a tobacco factory, densely occupied with single-story warehouses with a number of canopy trees scattered in between. The site is surrounded by Phaisingto Canal to the north, which was contaminated with urban runoff and sewage; Duang Phithak Urban Expressway to the west, which cut the site off from the adjacent community; an artificial lake to the east; and a hospital, hotel and the Queen Sirikit National Convention Centre to the south. In addition to the challenges of the site itself, the budget for this project was limited (ultimately, it was capped at 20 US Dollars per square meter), and the project was expected to be completed just 18 months. An additional challenge was that the project was overseen by the army, which did not have extensive experience managing landscape projects.

In addition to a high potential for flooding, the canal on the northern edge of the site is heavily contaminated. Except for the creation of a small museum for the tobacco factory and a sports center, there were no programmatic requirements for the site. Our team’s design was selected through an international competition.

3. Design Strategy

In addressing the multiple challenges of the site and its dense urban surroundings, the project was envisioned as a central park capable of providing holistic ecosystem services to the city, including storm water regulation to adapt to the changing monsoon climate, as a demonstration of a nature-based solution for filtering polluted urban runoff and providing life support for native species, as well as providing badly needed public space for daily recreational activities and other cultural services. Three strategies guided our work to meet these objectives:

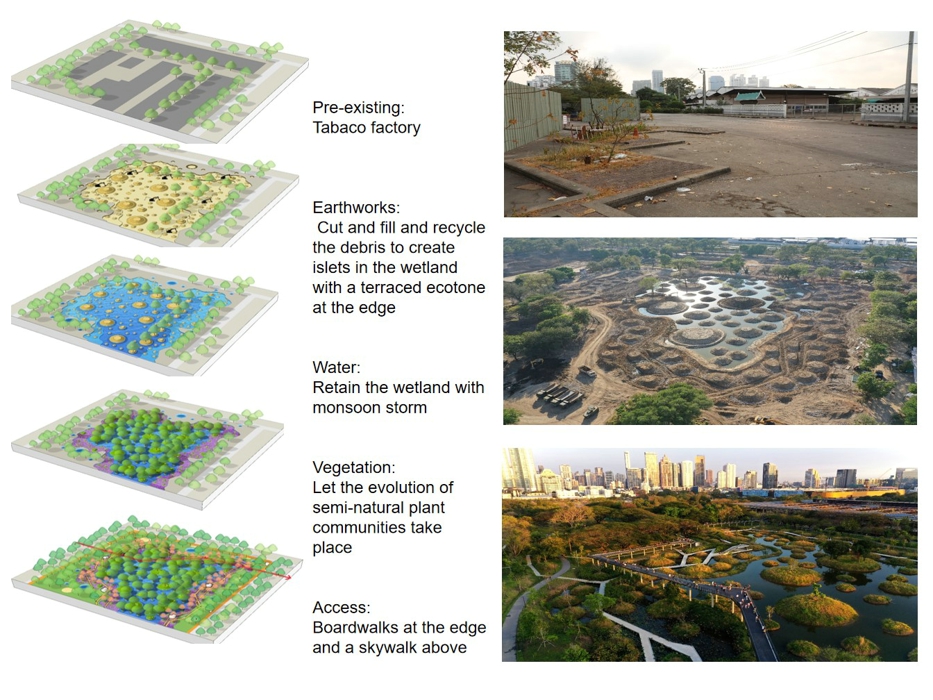

3.1 Reuse and recycle

All existing trees on site were preserved and integrated into the park design. To keep the budget low, all existing main roads were to be preserved. Existing factory buildings were repurposed to house the sports center and museum, which are fully integrated into the landscape. The demolished concrete materials were recycled for the earthwork foundation and paving.

3.2 Creating porosity and wetlands

First, cut-and-fill techniques were used to create wetlands dotted with islets. Without importing or exporting earthen fill, three constructed wetlands scattered with hundreds of mini-islands were created by simple cut and fill procedures to transform the impermeable, concrete-paved ground into a spongy and porous landscape, which is expected to retain up to 200,000M3 (23 million US gal) of storm water from the surrounding area during the monsoon season. This tilled landscape also transformed the otherwise hard clay surface soil into wet and spongy habitat, allowing a rich native plant community to establish itself with minimal irrigation or maintenance needed during the dry season. This modular landscape can be easily executed with a single excavator and minimizes dependence on skilled labor.

The foundation and foot of each individual islet was consolidated using recycled concrete materials. While pre-existing trees remain at the center of individual islands, young canopy tree seedlings were also planted on each of the newly constructed mounds at minimal cost.

Each of the three major wetlands is designed to have two depths: a shallow, terraced shoreline and a deeper core area. The terraced shoreline is connected to a linear water-quality remediating wetland built along the north and west edge of the park that filters contaminated water from the canal, and can improve the quality of 8,152m3 (2 Million US gal)of water from the poorest grade V to grade III each day. The amount of filtered water is sufficient to nourish the wetlands throughout the dry season and turn the shallow shoreline into a life-supporting ecotone that allows for establishment of a lush vegetative community.

Second, while the major roads were preserved and reused, a cut was made in the middle of each roadway to create a permeable bio-swale and flower bed that separates a bicycle lane and pedestrian path, helping to bring a more human scale to what were originally wide roads designed for heavy truck traffic.

Third, for the sports center and museum that make use of existing buildings, the principle of porosity was also applied to transform the factory buildings by daylighting portions of the roofs and allowing the living landscape to penetrate through the buildings’ concrete shells.

3.3 Fostering a low-maintenance “Messy Nature”

The modulated landform with diverse micro-environments was sown with seeds and planted with tree seedlings, creating a foundation for the subsequent evolution of a semi-natural plant community. The result is a low-maintenance mosaic of vegetation that will be continually and spontaneously enriched with native species. A symbiotic ecological interrelationship between fauna and flora is developing, and the “messiness” of the constructed wetland is creating a new, highly dynamic and diverse aesthetic that sharply contrasts with the surrounding urban landscape.

3.4 Creating immersive places for people

Multiple boardwalks were designed along the edge of the shallow wetlands that allow visitors to have immersive experience of urban nature. A skywalk runs through the tree canopies. That ties together the entire park, which for decades was sliced through by major roads, and creates a unique immersive experience amidst the tropical foliage.

4. Conclusion

Despite having been built on an extremely compressed timeframe, Benjakitti Forest Park has proven a great success. While much of Bangkok flooded last summer, the park and its immediate vicinity did not. The water-quality remediating wetland is performing well and produces enough water to keep the wetland alive through the dry season. A rich variety of birds and other wildlife has taken up residence in the park. The most striking achievement is that this naturally regenerative system is now the largest park in densely populated central Bangkok and attracts tens of thousands of visitors daily, who use it for a wide variety of activities, including jogging and cycling, family gatherings, school commencements, picnics, dates and wedding photographs. It has been celebrated extensively on social media as a new symbol of Thailand’s capital city.