Xi'an Yannan Park (Phase I)

Project Information

- Project Location:

- China Xi'an, Shanxi

- Project Scale:

- 121 Hectares

- Design Time:

- August 2016

- Build Time:

- September 2021

- Client:

- Xian Yanta District Infrastructure Construction Investment Management Co., LTD

Project Profile

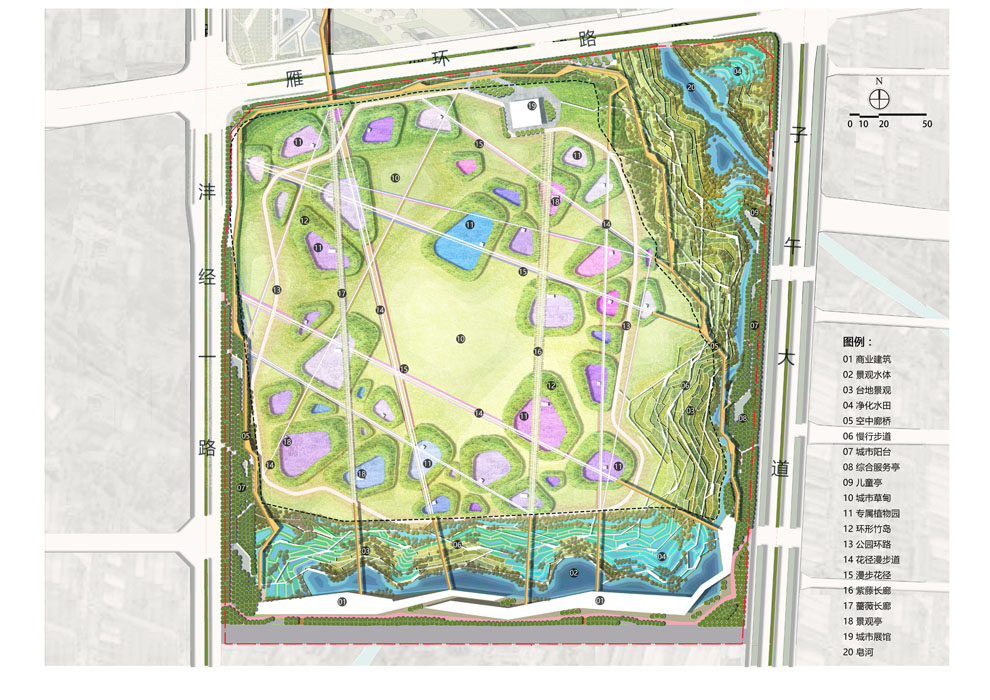

An Urban Oasis Protecting an Ancient Archeological Site: Xi’an Yannan Park

1. Project Statement

In the center of China’s ancient capital, Xi’an, a large, low-maintenance, 101-acre park was built to accommodate a wide array of public uses and to protect an underlying archeological site dating back to the Han Dynasty and before. Guided by heritage-protection regulations that prohibit excessive ground disturbance and deep-rooted plants, clusters of themed gardens were designed, each in an enclosure made of recycled urban debris and bamboo. Such a designed urban oasis not only created independent spaces for various otherwise-conflicting activities, but also brought a human scale to the otherwise forbiddingly large open space. The result is a truly lively urban oasis that blends everyday life into designed nature while keeping an archeological mystery safely hidden below.

2. Objective and Challenge

Today, Xi’an is a megacity with a population of over 10 million, but in the past it was the capital of some 13 dynasties over a span of more than 1,100 years. Archeological sites, some of which date back 7,000 years, are scattered throughout the city. Urban development is, of course, inevitable, but the protection of archeological relics is equally important—which raises an enormous challenge for urbanism and landscape architecture. In this context, smart urban planning preserves open spaces above archaeological sites while allowing urban development around them.

Surrounded by the booming urban heart of the city, and covered with dirt and debris from demolished buildings, the site of Yannan Park Phase-1 is 41 hectares (101 acres) in size and was designated as an archeological site with significant historical values and rich ancient relics underneath. A preliminary investigation discovered 25 ancient tombs and other archeological sites dating from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) back to the Neolithic Yangshao Culture, which authorities decided to protect in place. About half of the site, on higher ground, was designated as a sensitive protected area. The rest of the site has a concrete drainage channel running along its edge, with a steep slope dropping about 10~15 meters (33~50 feet). The urban drainage is heavily contaminated. In addition to a tight schedule and a limited budget of US $50 per square meter (about $5 per square foot), we were confronted with three major challenges:

No excessive ground disturbance or deep-rooted plants: In order to avoid damage to the archeological resources, the city’s cultural heritage authority ruled out any excavation deeper than 30 cm (about one foot) and the use of any woody plants that have a deep root system.

Accommodating diverse uses: A pre-design community survey suggested huge demand for public spaces that can accommodate diverse and sometimes conflicting recreational activities, including jogging, cycling, Yangge dance (a popular form of local folk dance in Xi’an), children’s play and family gatherings, camping, dog walking, gathering of elders and kite flying, among other activities. Fulfilling such diverse use demands within a single park is a significant challenge.

Bringing a human scale to a large open space: 101 acres is quite a large area in the middle of the city, and the creation of a diversity of experiences at a human scale was another significant challenge.

3. Design Strategy

In addressing the above site challenges and to achieve the project objectives, the following design strategies were developed:

3.1 Floating gardens sculpted by recycling urban debris on site:

To avoid any digging and deep-rooted woody plants and structures, the fill, composed of dirt and urban construction debris, was recycled on site to create raised walls of 1~3 meters (3.3~9.8 feet) high, which are ideal habitats for shallow-rooted bamboo to grow densely. The bamboo walls form spatial enclosures ranging from 10 ~70 meters (33~230 feet) in diameter. Each garden has a unique ground cover composed of perennial herbs and grasses, with unique colors, and is themed differently.

3.2 A matrix of themed gardens accommodating diverse programs:

Altogether, 39 pocket gardens were created to accommodate diverse uses and activities, leaving a central lawn open as a universally accessible urban common. Some pocket gardens were designed as amphitheaters for Yangge dancing and music, with a stage in the middle encircled with benches; two gardens at more-easily accessible sites have been designed as children’s playgrounds; some pockets are for selected herbs that create a tranquil, immersive space for meditation. Each garden is planted and equipped differently. Narrow entrances to the garden enclosures create an air of mystery and invite visitors to explore the landscape.

3.3 A web of paths creating various immersive experiences:

To balance the concerns of public accessibility and safety, eligibility and orientation of the spaces and explorative quality, a web of paths was designed to connect each of the gardens. Two major paths were designed as flower corridors that allow shortcuts across the park as well as provide shade. A cycling and jogging path encircling the park also functions as a service road and connects all the service facilities. Instead of a single lane of wide pavement, some of the paths are composed of parallel sub-lanes with plants in between to accommodate large influxes of visitors while still providing an immersive urban nature experience. A skywalk running along the edge of the park’s high ground allows visitors to enjoy the city skyline.

3.4 Terraces and low-maintenance vegetation to transform the concrete drainage channel:

To soften the steep slope down to the drainage channel, planted terraces were built; Old building materials including stones and tiles are used to build the retaining walls. Some terraces are constructed wetlands that filter nutrient-rich drainage water. Low-maintenance vegetation is widely used to bring nature back to city.

4. Conclusion

The park proved an immediate success. In the central common, people frequently camp at the edges; couples walk along the paths submerged among the native meadow; and grandparents accompany their grandchildren as they explore the “messy” meadow. In the pocket spaces, herb gardens are hidden mysteries that attract curious youngsters; children enjoy themselves on the playgrounds as their parents look on from the circular benches; elders sit in circle on a bench watching Yangge dancing; and music lovers play their instruments in the pavilions. On the paths, joggers enjoy the immersive natural setting along the circular route; families leisurely walk together on the skywalk, with urban nature on one side and the growing city on the other. Among many celebrated features, this urban nature oasis is intended as a balance of the four qualities of landscape configuration: coherence, complexity, legibility and mystery.